First mooted in 1849, proposals to construct a tidal barrage across the Severn Estuary to link south west of England with Wales have entertained generations of would-be developers. This mega project could generate 5% of the UK’s electricity needs, and would be equivalent to the same level of output as about two conventional 1GW power stations. Advocates of the scheme believe it will be a major step in delivering renewable energy.

With a potential capacity of 8640MW and an estimated output of 17TWh/yr, the Severn barrage has been described as a visionary project, unparalleled in scale. Reports also state that it would provide ancillary advantages in an area prone to flooding – the risks being highlighted in 2007 when large parts of the river catchment in the counties of Gloucestershire and Somerset were inundated – though the benefits from the possible alleviation of fluvial flooding and heavy rains would be minimal at best. Transport also features in the project concepts as the barrage could also potentially provide the basis for a new rail or road link from England to Wales.

The last main push at examining a tidal barrage was in the 1970s. Most recently, the Sustainable Development Commission (SDC), which is the UK Government’s independent advisory body on sustainable development – was charged to address tidal power, particularly in the context of a Severn barrage – published a report in October 2007 supported by an array of research reports. black-veatch (B&V) prepared one of the evidence-based research reports (No 3 – “Severn Barrage Proposals”)[1] .

SDC came out strongly in favour of a barrage scheme. It said the Government should seize the ‘unique opportunity’ and press ahead with the project that would help the UK meet its carbon reduction goals, provided it could be shown to meet tough targets under EU environment laws.

The Severn Estuary is of significance to nature conservation at the national, European and international levels and so has been afforded corresponding degrees of legal protection. Designated as both a Ramsar Site and Special Protection Area under the EU Habitats Directive, it is also in the process of being designated as a Special Area of Conservation. The estuary also comprises a series of Sites of Special Scientific Interest.

SDC’s chairman, Jonathon Porritt, said: “We are excited about the contribution a Severn barrage could make to a more sustainable future, but not at any cost. The enormous potential for a Severn barrage to help reduce our carbon emissions and improve energy security needs to be balanced against the impact on the estuary’s unique habitat as well as its communities and businesses.”

Shortlisted

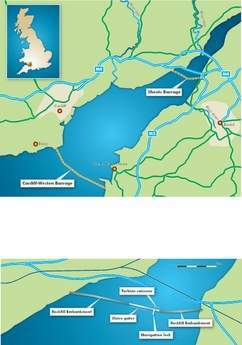

Studies have shown that tidal power barrage schemes with embankments of a minimal length result in significantly lower unit costs of energy than equivalent schemes with a longer embankment. With this in consideration, only two schemes shortlisted for inclusion in the SDC study remain as the most likely to generate electricity at an acceptable cost. These are the Cardiff-Weston and Shoots projects.

The Cardiff-Weston scheme is a proposed barrage between Lavernock Point, west of Cardiff, and Brean Down, south west of Weston-Super-Mare. It will operate as an ebb generation scheme but with the ability to use the turbines as pumps at around the time of high water to increase the amount of water stored in the basin. By pumping at low head, and generating later at relatively high head, a net increase in energy is obtained.

As the bigger of the two options, Cardiff-Weston would stretch 16.1km across the mouth of the estuary, cost an estimated £15B (US$30B) to construct and produce approximately 8.6GW of power. It is being developed by a consortium of contractors and manufacturers called the Severn Tidal Power Group (STPG), comprising Sir Robert McAlpine, Balfour Beatty Major Projects, alstom Hydro, Rolls Royce Power Engineering, Taylor Woodrow Construction and Tarmac Construction.

A second, more modest, scheme that would be sited upstream, called the Shoots barrage, calls for a 4.1km long project. The project is estimated to cost only a tenth of the former option and produce approximately 1GW of power, with an annual output of around 2.75TWh/yr. The proposal is basd on generating with flow from the basin to the sea, mainly during the ebb tide. The scheme was originally proposed during the 1920s and it is being developed by Parsons Brinckerhoff (PB) in response to the 2006 Energy Review.

These two schemes are considered to be the most prominent and well-studied proposals for a Severn barrage and the SDC selected them for further study. They have been described as good examples of potential projects in terms of scale, power output and potential impacts. The key technological aspects of the Cardiff-Weston and Shoots barrages are examined below.

Cardiff-Weston Barrage

At the proposed Cardiff-Weston barrage, each of the 54 caissons would house four 40MW bulb turbines with 9m diameter runners. A four-turbine arrangement is the preferred choice as testing showed overall economy and improved stability when one turbine water passage has to be dewatered for maintenance. Each passage can be closed off by inserting stoplogs from the deck, which allows for easy access to the entire area for inspection and maintenance. Similarly, stoplogs or “limpet” gates would be installed in all four water passages for each caisson being floated into position during construction.

After installation, most of the cells would be filled with concrete or sand to increase stability of the cellular structure caisson and provide added mass in the event of ship collision.

A 350 tonnes capacity crane, spanning a service road and the access openings above the turbine-generators, would provide the lifting capacity for maintenance of the mechanical and electrical equipment. An elevated dual carriageway road on pillars would provide a public road crossing of the estuary and the route for the power cables.

STPG proposes wants the turbine caissons built in several construction yards in the UK and, possibly, in mainland Europe. Building would take place in a dry dock and would be completed alongside a quay after the dry dock had been flooded and the part-complete caisson floated out. Each caisson would set down near the barrage, attached via two winch pontoons to a number of mooring lines, refloated and winched into final position.

The consortium has also favoured a Kapeller turbine-generator with four variable-angle runner blades with a fixed distributor. The main features of the arrangement is:

• No. of installed machines: 216.

• No. of machines in each control group: 24.

• Machine type: Kapeller.

• Runner diameter: 9m.

• Speed: 50rpm.

• Generator rating: 40MW @ 0.9 power factor.

• Generator terminal voltage: 8.6kV.

• Total installed capacity: 8,640MW.

• Transmission links to shore: 400kV.

The number of turbines required and the difficulty of assembling such numbers quickly in a pronounced tidal environment have led STPG to conclude that the turbines and generators should be pre-assembled as complete units onshore but not placed in caissons before float-out as that could cause the construction programme to extend unacceptably. Instead, when required, they would be transported two at a time by barge and off-loaded into position by a heavy-lift barge crane. The weight of each unit would be around 2,000 tonnes, well within the capacity of existing cranes.

During construction of the embankment for the barrage, an initial mound of rockfill on the seaward face would be built to gain control over the tidal flows and protect subsequent work on the basin side. The rock size required at any place would depend on the maximum current to be expected across the part-complete embankment. The design of the embankment would also include:

• A core of hydraulically-placed sandfill, protected from currents and small waves on the basin side by successive containment mounds of quarry waste or other cheap fill of suitable size particles.

• Filter layers between materials of different sizes to prevent migration of finer materials into coarser materials.

• Armour layers to provide permanent protection against wave attack.

• A wide crest to accommodate the road and the main power cables.

The initial rock mound would have slopes of 1V:2H, which would be suitable for a hard seabed or where the seabed material is sand or gravel. On the English side of the estuary, the embankment would have to cross deep, soft sediments. A flatter slope may be required to prevent slip failures.

STPG believes that the Cardiff-Weston barrage could be built within five to seven years, depending on the number of work yards provided for construction of the caissons.

The Shoots barrage

The design of the turbine caissons for the Shoots barrage option is based on the use of the “Straflo”, or rim turbine-generator, with a 7.6m diameter runner and two turbines to each caisson.

Above each pair of turbines there would be a 32m wide sluice, which would be much higher than the equivalent level for the Cardiff-Weston barrage, where the sluice gates would be fully submerged. PB has selected this level partly to help minimise the amount of silt carried into the basin.

Above the sluice water passage, on the basin side of the caisson, would be a continuous building which would house a travelling crane to service the turbines, turbine ancillary equipment and electrical equipment.

PB has based its cost estimate for the Shoots barrage on the use of concrete caissons. However, it points out that the caissons could be made from steel, which would permit the use of existing construction facilities in different parts of the country. If concrete was to be the construction material, the greater draft of the caissons compared with steel caissons would require a purpose-built construction yard.

The arrangement of the Shoots barrage includes sluices above each pair of turbines, except for two caissons adjacent to the ship locks. This would provide 13 sluices. Each caisson would have a 30m wide counterweighted radial gate. Additionally, there would be four sluices in caissons without turbines.

The embankment for the Shoots barrage would be built outside the deep water channel, on the shoulders of the estuary, and therefore is seen to present less of a construction problem than the embankment for the Cardiff-Weston barrage. PB plans for the embankment to be constructed in 3m lifts, with the outside faces protected by mounds of adequately sized rockfill to resist the maximum current flow at the time. Between the protection mounds would be a core of dredged sand fill with suitable filters between the sand and the protection mounds. The seaward slope would be protected by an armoured layer of rocks weighing 2 tonnes, and the basin slope with smaller material. This permanent slope armouring would be added as construction progressed, again to minimise the amount of partially completed embankment exposed to current and wave attack.

The electrical and mechanical equipment design for the Shoots barrage is at a preliminary stage of development compared with the Cardiff-Weston barrage, but PB puts the installed capacity of each “Straflo” unit at 35MW – less than the rival options due to the smaller tidal range at the proposed site. There would be a total of 30 machines, giving an overall capacity of 1,050MW.

PB believes Shoots barrage could be constructed and be ready for commissioning in about four years, with the fabrication of 21 caissons being completed within two years and all caissons placed in position three years after the start of construction works. Closure of the barrage would be achieved by raising the embankments above high-tide level while keeping the turbine and sluice openings clear to minimise flows over the partly-completed embankments.

Both barrage options would provide variable, but predictable, supplies of electricity to the transmission grid. The current planned network should have enough capacity for a barrage the size of Shoots without requiring significant network reinforcements. However, the larger Cardiff-Weston scheme would affect the wider system and necessitate a more detailed study of transmission needs. A split connection, sharing capacity between the transmission network on the north and south sides of the estuary, is likely to be needed.

The most recent report on financing the schemes, concluded in 2002, said that it was possible to envisage the Cardiff-Weston barrage being financed by the private sector. Such financing would be subject to the necessary policy instruments to achieve long-term security of supply contracts, and with capital grants to recognise the value of non-energy benefits. For the smaller Shoots scheme, though, it is anticipated that there may be sufficient interest not to require intervention.

The tidal lagoon alternative

The Severn barrage schemes are expected to be the principal focus of a new feasibility study into harnessing power from the waters of the Severn Estuary. Ministers and officials at the UK’s departments for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (DBERR), and Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), and other key branches of Government are drawing up terms of reference for what is expected to be the most comprehensive study of the estuary’s tidal energy potential. The study itself is expected to take at least 18 months to complete and its conclusions will not be made public until the autumn of 2009 at the earliest.

A serious alternative likely to feature in the feasibility study is the preferred choice of environmental campaigning organisation Friends of the Earth (FoE), which has proposed its own plan based on the concept of a series of tidal lagoons. These man-made structures would be built in the estuary to both fill and drain through turbines, generating power for the grid. Consisting of rock-walled impoundments, they would cover an estimated area up to 60% of that affected by a barrage, but their smaller configurations would not impound water in the ecologically sensitive inter-tidal areas of the estuary. As lagoons could be sub-divided, power could be generated at more states of the tide than would be the case for a barrage. The result would be a lower peak output but considerably lower construction costs.

However, lagoons are by no means a win-win solution to generating power from the Severn tides. They would require considerably more construction aggregates than a barrage and there could be significant environmental and social implications in sourcing up to 200M tonnes of rock, sand and gravel, it is estimated.

Tidal lagoons are not a new concept but is as yet unproven due to uncertainties over design, construction methods and physical impacts. In the absence of sufficient evidence to assess the long-term potential of tidal lagoons, SDC believes it is in the public interest to develop one or more demonstration projects in the UK to carry out the much-needed research.

Opportunity

SDC believes that there is a strong case to be made for a sustainable Severn barrage on a publicly-led, publicly-owned basis to ensure sustainability. It does, however, caution the Government about the implications of its decision regarding the construction of a Severn barrage and calls for analysis to show whether a true environmental opportunity is being presented. If compliance with EU environmental directives is found to be scientifically or legally unfeasible, then proposals for a Severn barrage should not be pursued, it says.

If the tides of the Severn are to be tamed, neither a barrage nor lagoons are without benefit or disadvantage. The Government’s feasibility study will no doubt attempt to address them all.

Additional reporting by Chris Webb

| Severn Barrage revisited |

|

With support from some high profile politicians, including former Prime Minister Tony Blair, the Severn barrage has sprung into the public consciousness yet again. There’s a deja vu sense of awareness of this latest rise to political prominence. First mooted as far back as 1849, the construction of a barrier across the Severn Estuary, linking south west England with Wales, entertained would-be developers throughout the 1970s, 80s and 90s. This mega-project, that could generate 5% of Britain’s electricity needs, has rebounded in response to the nation’s rallying call for clean, secure and reliable supplies of power from renewable sources. |

| Other Severn Barrage proposals |

|

Other Severn Barrage proposals |

TablesCardiff-Weston vs Shoots