In the face of rapidly falling costs of solar, wind and storage batteries, it is apparent that the energy market is changing faster than ever before.

The costs of renewables such as onshore and offshore wind have dropped by 40-50% in the last ten years, whilst solar and lithium ion battery storage costs have fallen by 70-80%.

The future of renewable energy is uncertain: Some believe large-scale onshore and

offshore wind, solar farms and grid-scale batteries will become dominant, while others predict a shift towards “decentralisation” – a takeover of smallscale behind-the metre solar and batteries which give consumers the ability to generate and store their own energy, decreasing their reliability on the grid.

As part of a major multi-client study, Pöyry has investigated how rapidly falling technology costs could transform the global retail electricity market – every

household could have its own rooftop solar, basement batteries and electric vehicles.

This raises the question: Will we see a significant uptake in decentralisation in the next

decade, or will changes in tariff structures and retail prices curb this natural development?

Retail electricity prices

Retail prices paid by households and businesses are affected by several different elements.

The primary part of the bill is the cost of wholesale electricity, but this is typically only a third of a consumer bill.

Large components of the bill cover the cost of the transmission and distribution network, policy support costs such as renewables subsidies and taxes such as VAT.

Despite the majority of policy support costs and network costs being fixed, on most

consumer bills these costs are increased per kWh of electricity consumed.

As a result, consumers are incentivised to reduce the energy they buy from the grid – in the past, this was logical as it encouraged energy efficiency.

However, with the rise of decentralised solar generation in countries such as Germany and the UK, consumers can opt instead to generate their own energy.

By installing solar panels, they can avoid paying their “fair” share of fixed system costs, but still rely on having a network connection.

This “free riding” could not only lead to customers without solar panels subsidising the costs of those with panels, but it could also result in a deeply inefficient electricity system, where large amounts of money are spent on unnecessary and expensive

behind the-meter generation.

Current tariff structures

Changing something as simple as the tariff structure could radically alter the investment incentives and the electricity market itself.

Pöyry ran two different scenarios through its power market model, BID3.

Modelling both wholesale and retail markets simultaneously, BID3 is a unique tool used for forecasting and analysis.

In the wholesale market, it models both the dispatch of power stations and investors’ decisions to build new plants.

In the retail sector, it models customers’ decisions regarding charging electric vehicles alongside their desire to buy solar panels and storage.

Different tariff structures mean that wholesale investors and retail customers have different incentives.

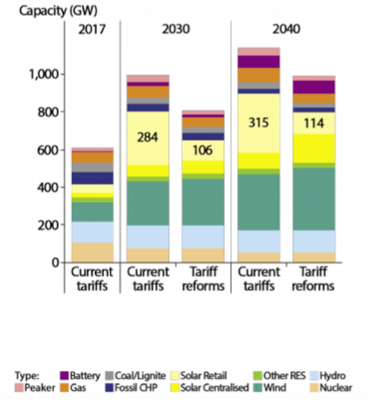

In Northwestern Europe alone the current tariff structures could result in the production of 280GW of behind-the-meter solar over the next 12 years.

During the summer, large amounts of solar energy would cause electricity prices to frequently fall to zero because there would be a surplus.

As a result, 30GW of grid-scale batteries would be built by investors looking to profit from the high spreads available.

An alternate solution

However, if regulators and governments altered tariff structures so that grid costs and policy support costs are paid on a per-household basis – rather than per kWh of electricity consumed – this would create a very different outcome.

In 2030, instead of 284GW of behind-the-metre solar, a mere 106GW would be produced.

The change in tariffs removes the incentive for retail customers to invest in solar panels.

We would see an additional 10GW of large scale solar and 10GW of onshore wind instead, as returns on these investments improve because prices would drop to zero less often.

Forecasts show that by 2040 there will be an even greater difference of 250GW in the amount of solar built, despite identical carbon emissions.

In both scenarios the reduction in carbon emissions and the demand remain the same, but the investment would be much greater with a continuation of current electricity tariffs.

In total, the savings from tariff reform could amount to €100bn ($114bn), simply by encouraging more economic investment decisions across the sector.

Furthermore, given the rapid uptake of new technologies, it is estimated that by 2025, half of all houses in Central and Northwestern Europe could invest in rooftop solar on economic grounds alone, with the savings on their retail bill outweighing the costs of installation.

There is also the risk of upsetting homeowners who decide to invest in solar panels, only to discover that changing tariff structures mean they no longer make economic sense for the consumer.

There is enormous value at stake, both financially and from the perspective of energy efficiency as we move towards a less fossil-fuel dependent future, which should encourage more governments to consider retail energy reform as soon as possible.