Child labour, diminutive wages and life-threatening working conditions have combined to create a mining network in the DRC that infringes on the most basic human rights and sullies the international market with a blood-stained supply chain.

Efforts to solve the conundrum have thus far proven ineffective, with most companies using easily-exploited paper-based certification methods to ensure minerals like cobalt – critical to future markets such as electric vehicles and battery storage – are sourced ethically.

Making matters worse for the wider market is the systematic control China has established over Congolese cobalt, the most abundant anywhere in the world, which could see other countries at a disadvantage once the electric automotive transition arrives and grid-scale energy storage comes of age.

In 2019, however, German supply chain auditor RCS Global has been busy developing and deploying a digital tool that harnesses blockchain to create a transparent network that lets companies accurately source the commodities they buy, potentially solving at least part of the problem.

Group CEO Dr Nicholas Garret said: “As the validator of the network, we will bring our vast experience working on responsible sourcing at all stages of the supply chain at all times.

“Our collective effort allows participating companies to progress from human-led risk management to technology-led impact generation in a highly efficient and cost-effective manner.

“Augmenting crucial human expertise and experience, this is a demonstration of technology for good, empowering vulnerable communities and protecting the environment – we are proud to be a member of the network.”

The cobalt challenge

In an argent rendition of 1848’s Gold Rush, a single silver-tinged metal has over the past decade caught the world’s attention: Cobalt.

Critical to the construction of batteries, the commodity has emerged as central to some of the industries set to determine the future.

Roughly 10kg of the precious resource is needed to make an electric car, for example, and, without it, the feasibility of grid-scale battery storage is severely compromised.

The vast majority of the planet’s cobalt is located within the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where a plethora of interested parties are engaged in a frantic contest for control over mining operations.

The biggest issue facing the local population and the market at large today, however, is the litany of human rights abuses that litter the country’s mining supply chain, and the investor uncertainty that its dilapidated infrastructure has subsequently sowed.

Child labourers and sex workers typically below the age of 17 are a common sight across the artisanal Congolese cobalt mining network owing to its lack of regulation, with hold-ups at the hands of a corrupt military and regular landslides creating a state of harrowing and perpetual apprehension.

And any cobalt trader that emerges from the miasma with supply to sell is immediately subject to illegal taxation by nefarious state institutions – another problem the Congolese government and the wider international community have so far failed to solve.

How does RCS’ digital tool work?

Piloted at Huayou’s industrial cobalt mine in the DRC by way of a pilot that includes Ford and IBM, RCS’ handheld device allows its users to scan barcodes that feed key pieces of information about a given ore supply to the cloud, including its weight, when it was tagged and by whom.

Provided and allocated to certified suppliers by the government, the barcodes, once scanned, create what RCS has called an “immutable audit trail” via blockchain, that features corresponding data to provide evidence of the supply’s production from the mine to the end manufacturer.

The company has also confirmed that any participants in the network will be validated against responsible sourcing standards developed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Lisa Drake, vice president for global purchasing and powertrain operations at Ford, said: “We remain committed to transparency across our global supply chain.

“By collaborating with other leading industries in this network, our intent is to use state-of-the-art technology to ensure materials produced for our vehicles will help meet our commitment to protecting human rights and the environment.”

Manish Chawla, general manager for global industrial products at IBM, added: “With the growing demand for cobalt, this group has come together with clear objectives to illustrate how blockchain can be used for greater assurance around social and environmental sustainability in the mining supply chain.

“The initial work by these organizations will be used as a precedent for the rest of the industry to be further extended to help ensure transparency around the materials going into our consumer goods.”

China’s whip hand

While RCS might have succeeded in developing a tool that could clean up the Congolese supply chain and potentially the global mining network, the cobalt market faces another problem.

China has got out in front of its fellow investors and secured a monopoly over cobalt in the DRC – a particularly strong position to hold given the scarcity of the commodity outside of the politically volatile country.

With no practical alternatives to the metal available as far as the construction of batteries is concerned, this single-country control could create a trading bottleneck that will see prices in regions away from China sky-rocket.

Mike Orme, a senior analyst with market intelligence firm GlobalData’s thematic research team, said: “China controls seven of the largest DRC mines, led by Molybdenum, and in the process over half DRC’s cobalt supplies.

“Moreover, the owners of the mines it doesn’t control mostly sell to Chinese traders and Chinese cobalt refineries in any case, and that includes Glencore, owner of the Katanga mine, DRC’s single largest mine.

“China’s refineries, fed in large part by feed stuff from Chinese owned mines, supply 80% of the world’s battery-ready high-grade cobalt.

“Control of the critical raw materials, including cobalt, and the world-beating processing and manufacturing capacity will determine who holds the balance of industrial power in the automotive and energy storage industries

“In the global scramble to secure forward supplies and escape the vagaries of the spot market, China holds that whip hand.”

In theory, western countries like the US and those in Europe, along with other economic powerhouses like Japan and India, would have to go through the Chinese in order to produce plug-in cars and batteries if the country’s domination over its supply is as wholesale as has been told.

Ivan Glasenberg, chief executive of Swiss mining company Glencore, said in March last year: “If cobalt falls into the hands of the Chinese, you won’t see electric vehicles being produced in Europe.

“[Europe is] waking up too late – I think it’s because the car industry has never had a supply chain problem before.”

Dwindling prices hit global markets

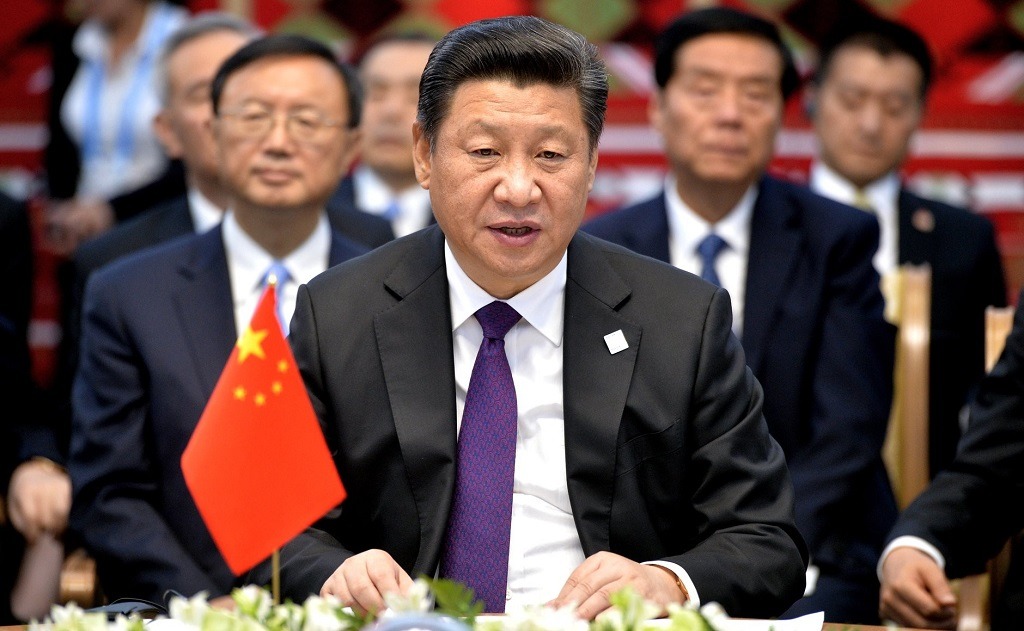

The impact of a single-country cobalt monopoly are already being felt, according to some analysts who have laid the blame for mineral’s plummeting prices in 2019 at Chinese president Xi Jinping’s feet.

China’s demand for cobalt and the mineral’s price both reached their peak in 2018, and both subsequently dipped heading into this year, slashing its prices by as much as 60%.

The strain is being felt far and wide: In April this year, shares in Huayou Cobalt, the largest cobalt refiner in China, fell 10% following a poor first quarter performance that it blamed on the commodity’s price collapse.

The company’s profits over the first three months of 2019 were all but non-existent compared with the year previous, down to $1.8m from more than $120m.

It was not the only refiner to suffer — just a week prior, shares in Umicore fell by 17% as a consequence of cobalt’s plummeting price, considerably more than the 10% the Belgium chemicals group had predicted.

And more recently, Glencore announced plans to cease production at the Mutanda mine, located in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), as operations there are no longer “economically viable”, according to a letter seen by the Financial Times.

It read: “Unfortunately due to the significant decrease in the cobalt price, increased inflation across some of our key input costs (mainly sulphuric acid) and the additional taxes imposed by the mining code, the mine is no longer economically viable over the long term”.

The company’s financial figures have followed a similarly downward trajectory to cobalt in 2019, with a 32% fall in company earnings over the first half of the year.

CEO Ivan Glasenberg said: “Our performance in the first half reflected a challenging economic backdrop for our commodity mix, as well as operating and cost setbacks within our ramp-up and development assets.”