It would double what is already the longest sub-sea pipeline in the world and significantly reduce the European Union’s carbon emissions – but the Nord Stream 2 project is not without controversy.

Then-UK foreign secretary, Boris Johnson joined the US, Poland, Ukraine and the Baltic states in condemning Germany and Russia’s plans to press ahead with the construction of the huge gas pipeline between the two countries.

It has caused growing conflicts between the Europe and the US due to the impact it would have by increasing the continent’s reliance on Russia for natural gas and effectively cutting out countries in between from any deals. This is currently under scrutiny and the German Federal Network Agency will decide by the end of May whether Nord Stream 2 will be subject to European regulation covering access of third-party countries.

In addition to the conflicts, the US also threatened sanctions on European companies involved including Royal Dutch Shell, Austria’s OMV, France’s Engie and Germany’s Wintershall and Uniper.

On 21 December 2019, it was announced that work on laying ocean pipelines had been suspended due to concerns of US sanctions being enacted.

In January 2020, Russian president Vladimir Putin claimed that construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline would be completed “by the end of this year, or in the first quarter of next year”.

Works, such as completing landfalls and offshore works stabilising the pipeline, are continuing as planned, according to Nord Stream 2.

But what actually is the project and why are Russia and Germany so determined to see it through?

What is Nord Stream 2?

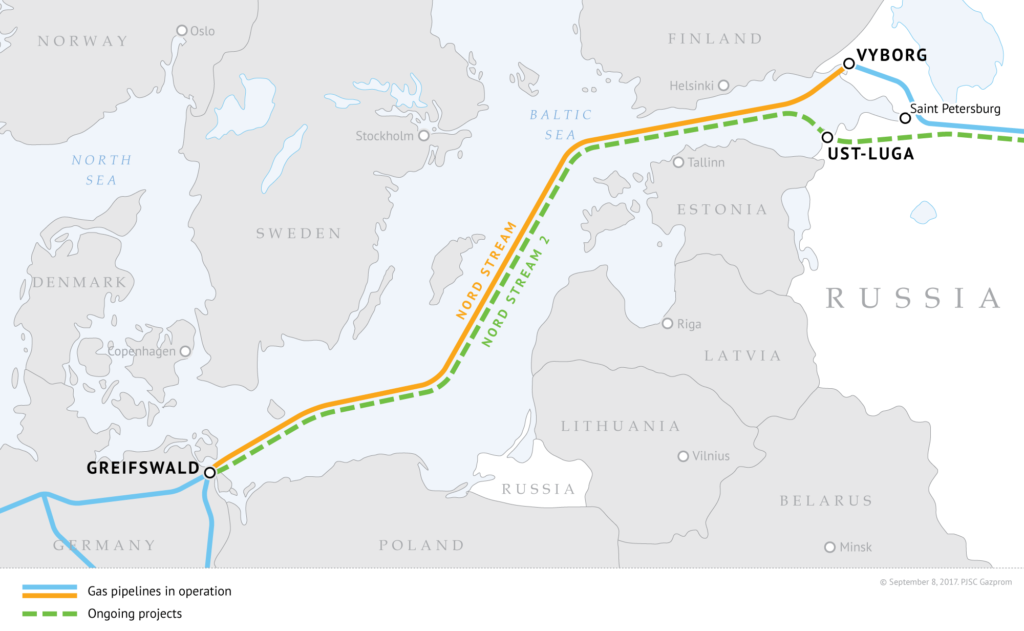

The complex project is an addition to Nord Stream 1, which opened in 2011 and runs from Vyborg in Russia to Greifswald in Germany.

Nord Stream — the longest sub-sea pipeline in the world at 759 miles — is owned and operated by Nord Stream AG, whose majority shareholder is the Russian state-owned energy firm Gazprom. Nord Stream 2 is owned and, when commissioned, will be operated by Nord Stream 2 AG, also a subsidiary of Gazprom.

The 745-mile Nord Stream 2 pipeline would carry about 51 billion cubic metres of natural gas underwater using 200,000 pipes from Russia to Germany, while bypassing Poland and other countries in the region.

According to the consortium, using gas to power electricity creates about 50% fewer carbon emissions per kilowatt-hour than using coal.

It means the Nord Stream 2 project could also save about 14% of the EU’s total carbon emissions from power generation – if natural gas from the pipeline was used to replace coal-fired power stations.

For Germany, the construction has already started and the project means more gas despite nuclear and coal power plant phasing out.

The delayed Nord Stream 2 project is now slated to be completed by Q1 2021, and will make its way through the Baltic Sea to Germany and follow the track of the existing Nord Stream 1 – making the pipeline’s annual capacity 110 billion cubic metres.

Who benefits?

Russia is likely to benefit the most from the Nord Stream 2 as it currently supplies 34% of European gas – and this would rise to more than 40%.

German officials have claimed the pipeline leads to economic savings by getting rid of transit fees, as the transit countries would be bypassed, while the consortium says it would better connect Europe’s gas network.

It will, however, destroy the concept of diversifying supplies, and Ukraine has been in opposition against Russia and Germany – as it would lose natural gas transit revenues of up to £539m annually.

However, Germany has defended the project, commenting on how the Nord Stream 2 is for commercial purposes and not political.

It has also said the project is needed to fill an energy gap left by the phasing out of nuclear plants.

Here’s what’s being said

The US administration has long put pressure on Europe to abandon the deal in exchange for avoiding a trade war and has even gone as far as threatening sanctions against businesses involved in the project.

A senior state department official in the US said it would cause a security threat as it would give Russia the chance to install “undersea surveillance equipment” such as “listening devices” in the Baltic.

However, President of Russia, Vladimir Putin was not willing to compromise and, during a press conference with German chancellor Angela Merkel in 2018, he said: “We will continue gas shipments (via Ukraine) as long as they are economically justified.”

In Putin’s defence, Ms Merkel said: “Germany believes Ukraine’s role as a transit country should continue after the construction of Nord Stream 2… it has a strategic importance.

“Germany, Britain, France and all our EU colleagues support this deal and will continue to support it.

“The deal is not perfect, but it is better than a lack of a deal. It guarantees more control and more security.”

Britain had tried to keep a low profile on the topic, but then-UK foreign secretary Boris Johnson spoke out in a letter he released to pro-Polish British MPs.

Johnson said “it is right to highlight the divisiveness of this pipeline across Europe”, adding that “Euro-Atlantic unity remains our strongest tool in standing up to malign Russian activity.”