The ascent of US shale has had a profound impact on global oil markets, but amid the coronavirus crisis, it has become the sector most at risk in a broader trend of investment decline across energy industries. NS Energy takes a look at how the low-price environment has affected the outlook for this prolific industry, the prospects for production and the potential for recovery in investment appetite.

US shale is poised to suffer a 50% drop in investment activity this year, piling further pressure on a sector already taking extreme measures to survive the pandemic-triggered oil crash.

Operators across the world’s largest oil-producing industry are facing huge financial pressures brought on by a global oversupply that sent prices crashing at a time of record-low demand, and in many cases have taken the unusual step of shutting in production.

Although the market is now showing signs of rebalancing as lockdowns ease and production cuts are enforced, there remains severely weakened appetite for investment in this low-price, demand-sapped environment.

US shale the hardest hit in an industry-wide investment drought

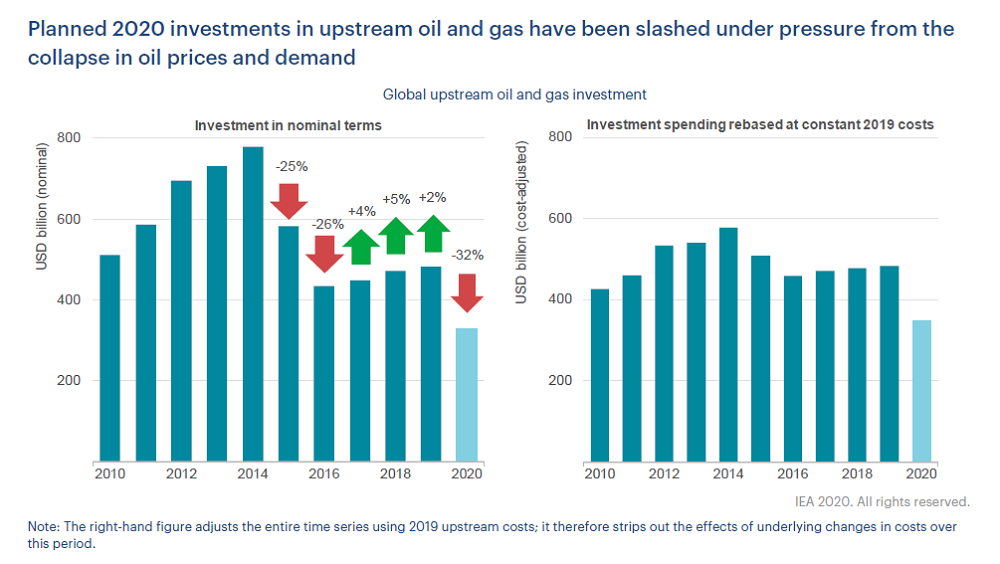

It is a problem facing the oil and gas industry as a whole, with investment across the spectrum expected to decline by almost a third this year, according to new analysis by the International Energy Agency (IEA), but shale will be by far the worst-affected, particularly the smaller independents.

Recent analysis from Rystad Energy placed as many as 73 exploration and production (E&P) firms in the US at risk of filing for bankruptcy if the situation continues without intervention from the federal government – even with the recent price rebound for the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) oil benchmark.

According to the IEA’s latest investment outlook: “The shale industry as a whole was struggling to generate significant free cash flow at prices above $50 per barrel (WTI), so it is no surprise that at oil prices of $30 per barrel or less, the outlook for many highly-leveraged shale companies looks bleak.

“Some are already seeking bankruptcy protection, with Whiting Petroleum being the first of the larger producers to do so, and strains will intensify for a good portion of the sector. We estimate that upstream spending on shale (tight oil and shale gas) is set to decline by 50% year-on-year in 2020.”

Current market crisis unlike those that came before

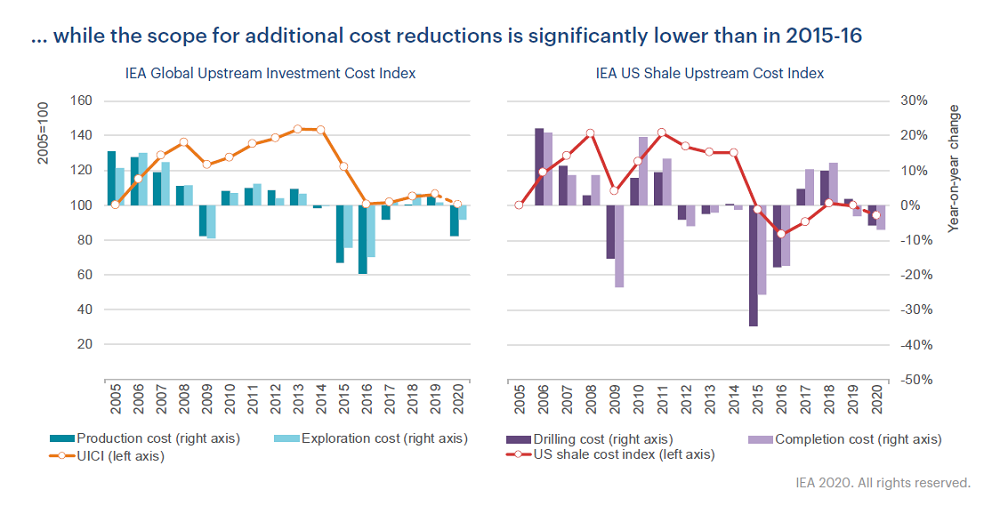

US shale has faced market pressures before, but unlike the last oil crisis of 2014, there are now fewer places for companies to turn in terms of cost reductions or efficiencies, meaning lower spending activity is increasingly becoming the norm.

The IEA report adds: “The pressures on companies may appear similar to those that followed the last price fall in 2014-15, but in practice the cost-cutting options open to companies today are much more constrained.

“The investment projects that are on the table today are already much leaner and cost-competitive than they were five years ago, having undergone intense screening in the meantime for opportunities to trim excess costs via simplified and standardised project designs.

“Today there are few prospects for companies to sell upstream assets as a way to service debt or raise capital. The fall in the oil price also means that companies that use reserve-based lending face a significant revision in their value of available debt.

“This will hit small and medium-sized companies particularly hard (not just in shale). With the possibility of more constrained access to capital in the future, one consequence of the current crisis may well be a consolidation of the industry towards larger players with deeper pockets.”

Rig count decline reveals dwindling appetite for investment in US shale

The combination of these market forces – exacerbated by the Saudi-Russian price war in March that targeted US shale in a tussle for market share with large volumes of cheap crude – has led many producers to take the drastic action of shutting in production at wells.

Rig numbers – a key indicator of production activity – across prolific US oilfields such as the Permian Basin have fallen significantly since the start of 2020, with data compiled by oilfield services firm Baker Hughes showing a 67% decline in rig count last week compared to last year, totalling 318 across the entire US.

“Rig count is widely considered to be one of the most important indicators of investment appetite by E&Ps,” according to research firm Rystad Energy in a recent analysis. “Not only does it illustrate the actual drilling activity in the market, but it is also a key metric of consumer confidence, closely related to price developments.”

Oil and gas production in the US has been widely tipped for a substantial decline this year, with the IEA suggesting recently the country will be the single biggest contributor to global output declines this year, outpacing even Opec+ members with a full-year curtailment of around 2.8 million barrels per day (bpd).

According to analysts at Rystad, US oil production will reach a two-year low in June of around 10.7 million bpd – a huge decline compared to the almost 12.9 million bpd achieved just two months ago in March.

US shale is resilient enough to recover, but it will be left permanently changed

A slight recovery is on the cards for the rest of the year, but oil output will not surpass 11.7 million before 2022, according to the research.

“A major portion of the decline throughout the second quarter of 2020 stems from production curtailments and not from natural decline due to the collapse in [fracking] activity,” says Rystad’s head of shale research Artem Abramov.

“The recovery will not be distributed evenly across major US oil basins and, in fact, we expect the Permian and Gulf of Mexico (along with Alaska) to gain market share throughout 2020 and 2021.

“Yet even in the Permian Basin, we might need to wait until 2022 or a better oil price, before it can again achieve its first-quarter 2020 production record of close to five million bpd.”

Despite all these pressures, the IEA believes that US shale is resilient enough to withstand a crisis that will nevertheless transform the face of the industry.

The energy watchdog says: “The damage to investor confidence and to available financing will take time to repair, but it is too soon to write off shale.

“Drilling new wells would naturally require a rebound in prices – for most plays and operators, well into the [range of] $40 per barrel – but shale has proven its resilience in the past and investment can pick up when market conditions allow.

“After a wave of bankruptcies, though, it will be a different industry from the one that we have known until now.”