Lawmakers and operators are increasingly thinking about how defunct mines can close sustainably, especially if revamped sites can go on to provide new opportunities for local residents. World Mining Frontiers writer Andrea Valentino chats to Dawn Brock, a specialist in mine closures at the International Council on Mining and Minerals, about how legal changes have made environmental mine closures more common, the importance of drafting local help when planning restorations, and how this vital corner of mining life might develop in future.

By the standards of the Soviet Union, the Karamken gold mine was a thrusting example of socialism in action. Opened in 1978, amid thick forests of spruce and fir in Russia’s far east, it quickly became a symbol of what the worker’s state could manage with a little spit, grit and rigorous production quotas.

Over those years, in fact, the mine was producing so much gold that its staff could afford to make a joke or two. Asked if his country would one day fulfil Lenin’s dream of using gold to build public toilets, Karamken’s manager replied, “We believe in it.”

Like the idealists who built it, the mine at Karamken is gone, shuttered as its gold reserves dwindled in the 1990s. Yet if the bustle of trucks and drilling is a distant memory, less happy reminders of Karamken’s former life still remain.

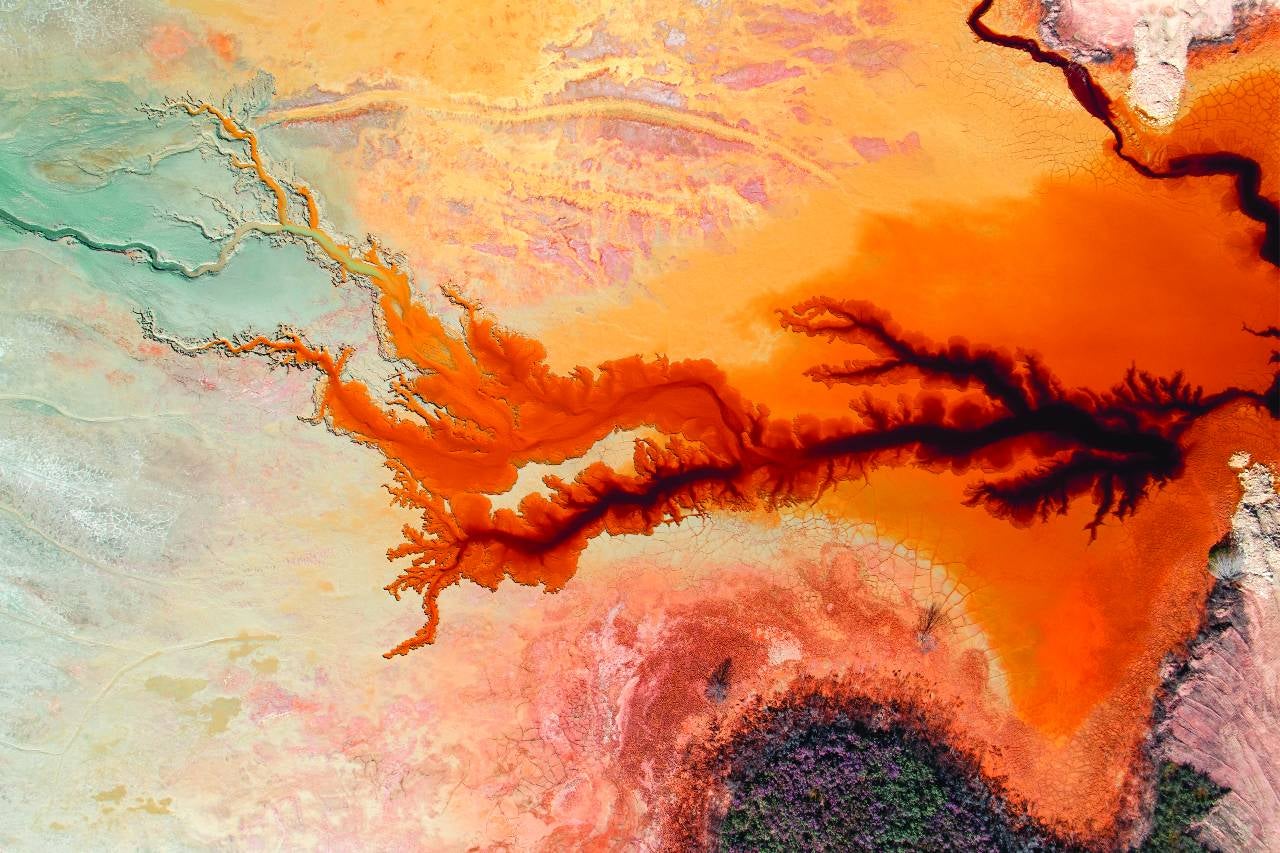

Like so many ex-Soviet mining sites, this place has left behind a catastrophe that seeps into the surrounding landscape like a smudge of wet ink. Just look at the tailings, the waste left behind from when gold was still being extracted.

Because the dam built to contain this sludge has long since rotted away, poison has for years slipped into nearby streams. Even 3km downstream from the dam, cyanide levels are still dangerously high, killing fish and endangering local villagers.

And if there are many places like Karamken scattered across Russia and the Soviet Bloc, they’re not unique. From Canada to Germany, mine closures and decommissioned sites are an environmental menace, with polluted water just one in a long list of hazards. From putrid soil to drowning risks, these sites can wreak havoc with places and people long after the miners themselves have hung up their picks.

All the same, the situation is far from hopeless. Pushed along by stricter regulations, and perhaps also an understanding that careful decommissioning can bring financial rewards, many mining operations are starting to change tack.

By working closely with local communities, they can keep happiness and prosperity rolling – long after a mine has shut its gates.

If you want to understand how mine closures have waxed and waned over time, you could do worse than ask Dawn Brock, who spent five years working as a rehabilitation and closure consultant at Golder Associates, a distinguished consulting company.

Then, in 2017, she joined the International Council on Mining and Minerals (ICMM), working on its environmental stewardship and social progress programme – a scheme with a special focus on mine closures. It is work that Brock has continued ever since, especially given that the politics and practicalities of mine decommissioning have only grown in importance.

One reason for this, suggests Brock, is mining’s shifting fortunes in the court of public opinion. With commodity prices veering from boom to bust and back again, and companies increasingly harried by politicians and NGOs, she says that there’s now increasing “pressure on mining companies” to keep their environmental houses in order.

Look at what legislatures around the world are doing – especially in more established mining nations – and she surely has a point. In Brazil, for instance, the government now expects mining businesses to monitor waste disposal systems after shafts are wound up. Across the Andes, the Chilean geology and mining service hopes to speed up mine closures by over 50%, market researchers BNamericas has reported.

Other lawmakers have taken even more drastic steps. In Western Australia, for example, operators must now publish detailed plans encompassing everything from the cost of closures to what sites could be used for in future.

Green evolution

From the perspective of both miners and lawmakers, you have to imagine the spectre of environmental chaos from mine closures – and, of course, the grim headlines that follow – is prodding change along. In Germany, for example, the Wismut uranium mine left behind over 50 million tonnes of toxic sewage.

Mismanaged tailings can also cause problems all on their own. Echoing the example of Karamken, a recent study in Alberta, Canada found that disused mines in the province posed a risk to the environment for what is essentially an indeterminate amount of time.

No wonder, then, that Brock describes the potential negative consequences of mine closures as “significant” to both local communities and the environment at large. Still, if the stick of pollution is one way to understand the increasing interest in mine closures, the carrot of company bottom lines probably matters too.

On a planet where decent land is increasingly scarce – ScienceDirect estimates there are over a million abandoned mines – companies that thoughtfully redevelop a defunct location could see profits soar. The crucial theory here, Brock notes, is something known in the industry as ‘relinquishment’.

“This is often the term used to refer to activities that have the possibility of generating income from closure activity,” she says. “And that can help either in terms of facilitating the transfer of the site to a third party, or for relinquishment purposes.”

Mine closures can leave a positive environmental legacy

Until it closed in 2001, the Sullivan Mine served as the focal point and income source for an entire town in British Columbia, Canada. At its peak, it employed over 3,500 people in nearby Kimberley – equivalent to nearly half the settlement’s population – and disgorged everything from zinc to lead to iron sulphides.

Yet as early as the 1960s, Teck, the mine’s owner, was conscious that the boom times couldn’t last forever. Working together with the miners themselves, Teck busied itself for the future by investing heavily in the diversification of Kimberley’s economy – and in 2015 finally announced it was done.

By any standard, the wait was worthwhile. Boasting a ski hill, a solar power plant, hotels and restaurants, Kimberley is now a thriving and lively tourist town.

Happily, the experiences of the Sullivan Mine is far from unique. Practically everywhere you look, you can find similar stories of mines reborn.

A striking example comes from Indonesia. Rather than just turning tail and leaving, PT Newmont transformed a site in North Sulawesi province into a botanical garden, filled with mahogany and teak.

Brock, for her part, highlights a scheme she’s working on in her native South Africa. “We’re potentially piloting a smallholder agriculture cultural project,” she explains, “which will bring in other stakeholders and local communities, training them to be able to continue agricultural practices on the rehabilitated site.”

This last point feels especially important. For if these projects are scattered across countries, they’re all intimately linked to the people who actually live nearby. That’s particularly vital, adds Brock, given so many ex-miners come from indigenous communities.

In the case of Australia, for instance, 3.1% of mine workers belong to the Aboriginal population, compared with 2.5% across the economy at large, according to one University of Queensland report.

Thoughtful post-life planning for mines can augment the stake such communities have in the land itself. Partnering with local residents can offer practical benefits, too, whether that’s in helping to choose which plants and flowers to reintroduce or in monitoring wildlife numbers.

In the coalfields of Appalachia, for example, mining interests and environmentalists are working with local hunters to reintroduce thousands of elk.

New technology is also helping operators in their bid to refine the waste and pollution that is often left behind after the closure of mining sites. Several operators in the US, for instance, are using bacteria bioreactors to make rock and soil less acidic.

Not that the way forward always has to be so technical. Based in New Zealand, Solid Energy has developed an ingenious way of loading ruined topsoil with nutrients – by taking waste from local toilets.

Planning is key

Whatever the technique, Brock and her colleagues at the ICMM are working hard to make the whole process of post-closure restoration far simpler. One recent example is the Closure Maturity Framework, a tool that helps mining companies categorise the status of their sites, and promotes conversation between different strands of a company.

The point here, adds Brock, is to “have open discussions about what actions need to be implemented to move from A to B”.

Considering how many mines have been successfully decommissioned over the last few years, might such planning soon become the norm everywhere?

From a financial perspective, you certainly have to think so. After renovating the Sullivan Mine, for instance, Teck went ahead and acquired the solar power business that was built on the site – and which now generates around C$250,000 in revenue each year.

With money to be made, Brock is bullish about the decades ahead.

“Even just in the last ten years, we’ve seen such a big shift in the way mining companies are looking at closure and how they implement it,” she says, adding that all those stricter regulations are helping too.

“Mining companies are being held responsible for their actions, and if they want to continue operating in the country, they need to ensure that there’s a positive legacy left behind.”

This article first appeared in World Mining Frontiers magazine.