Net-zero pledges made by the world’s biggest oil and gas producers need to be backed up by clear interim emissions targets based on credible pathways and proven technologies, urges a new report from financial think tank Carbon Tracker.

Many of the international majors have now adopted strategies to address climate change, but “even the best plans stretch credibility”, the group says, with many reserving the option to increase fossil fuel production in the years to come.

A landmark report this month from the International Energy Agency (IEA) said future investments into new oil and gas supply projects are no longer needed in a net-zero pathway, and urged producers to concentrate only on developing their existing assets.

The recommendation was a “jarring wake-up” for those in the industry who thought they might “finesse their way through the energy transition”, said Fred Krupp, president of the Environmental Defense Fund, a prominent US-based advocacy group.

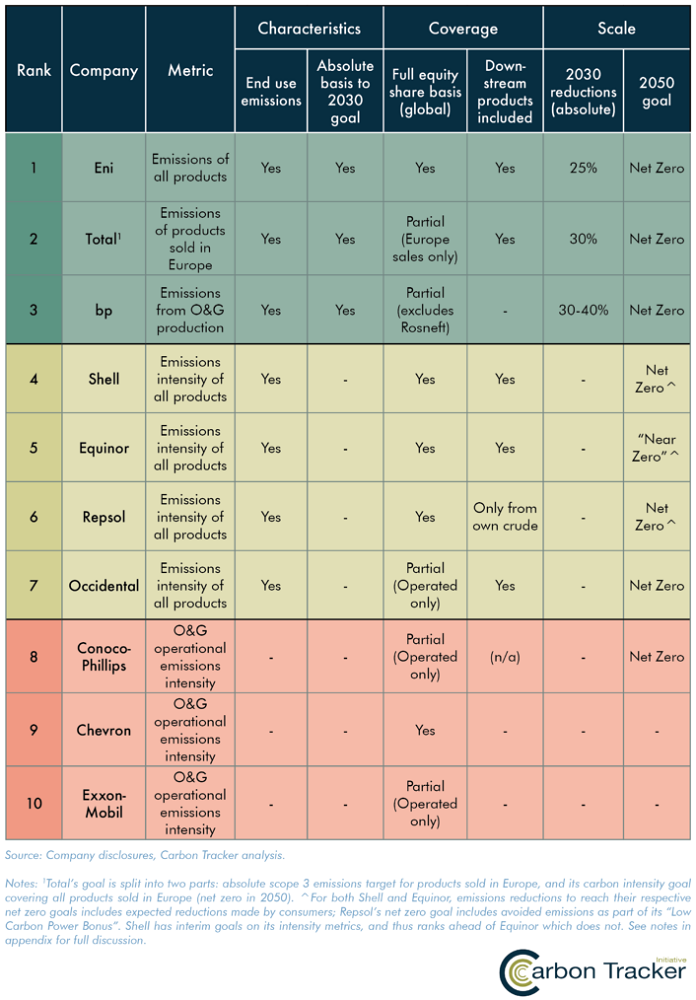

Carbon Tracker’s analysis finds while ten of the world’s largest oil and gas companies have strengthened their climate policies this year, none of these plans go far enough to give investors confidence they are aligned with the Paris Agreement.

Clear, incremental targets are needed to enable investors to judge the pace these businesses are adapting to the energy transition – and so the level of financial risk they face if demand for their products falls as low-carbon alternatives proliferate.

“Net zero is not enough – it’s the pathway that matters,” said Mike Coffin, senior analyst at Carbon Tracker and the report’s author.

“To align with the Paris Agreement, companies must commit to absolute reductions in carbon emissions from their oil and gas products, with strong interim targets and a credible implementation plan.”

External pressure is mounting on oil and gas companies to set bolder targets to cut emissions

The issue of Paris alignment is a growing concern for major investors either conscientious of their impact on climate change or worried about diminishing financial returns from “stranded assets” as the world’s energy system continues to shift towards lower carbon.

BP and Shell faced opposition earlier this month from some shareholders who want a faster pivot away from carbon-intensive operations, while at their own AGMs this week both Exxon and Chevron were rocked by shareholder rebellions demanding a change of direction more tightly focused on climate issues.

A majority of Chevron investors went against board recommendations to vote in favour of a proposal to cut the company’s Scope 3 emissions – those associated with end users.

Meanwhile Exxon’s shareholders delivered a stunning rebuke by voting to appoint at least two new board directors nominated by an activist investor fund that had publicly campaigned for a stronger climate strategy.

This “watershed moment” for climate accountability in Exxon’s boardroom sent an “unmistakeable signal that climate action is a financial imperative – and leading investors know it,” said Krupp.

“It is no longer tenable for oil companies like ExxonMobil to resist calls to align their business strategies with a decarbonising economy.”

Interim goals, Scope 3 coverage and proven technologies are key to a credible net-zero pathway

Among the recommendations from Carbon Tracker for a more palatable climate strategy is setting interim targets for absolute emissions reduction by 2030 – meaning not just emissions intensity, and not so distant as the 2050 deadline for reaching net zero.

“A stated goal some 30 years hence is one thing, but however ambitious it is, there is little incentive for current management to act to reduce emissions,” the analysis states. “To drive real change, it’s critical that companies have interim goals.”

Some have done so, namely Eni, Total and BP, which rank highest on the think tank’s comparison of stated emissions targets among the major producers. Eni is the only firm to have no exclusions from these targets – Total’s account only for product sales in Europe while BP’s policy excludes is stake in Russia’s Rosneft.

Shell, Equinor, Repsol and Occidental Petroleum have each set 2050 net-zero targets, but have only committed to a reduction in carbon intensity, leaving open the possibility they could increase fossil fuel production if balanced with enough renewable capacity.

Both Exxon and Chevron are yet to align themselves with a long-term net-zero goal.

Companies should also account for Scope 3 emissions from the end use of fuel products in their strategies, says Carbon Tracker, as well as basing emissions reduction plans on proven technologies and mitigation methods.

Most existing plans count on carbon capture utilisation and storage (CCUS) systems and negative emissions technologies (NETs), which despite growing interest remain nascent industries unproven at the scale envisioned.

Carbon offset schemes like tree planting, meanwhile, have huge implications for land usage that should be closely scrutinised by investors for their practicality. The analysis gives the example of Eni and Shell, which together plan to plant enough trees to forest an area larger than the size of Bulgaria.

“All companies in the study rely on CCUS but there are just 28 projects operating worldwide, on average capturing just 1.5 million tonnes of carbon dioxide annually,” the think tank said.

“Occidental Petroleum plans to use massive amounts of direct air capture (a NET) to offset emissions, but although there are pilots the technology has not yet been demonstrated at scale.

“The implication for investors is simple. The most effective way for oil and gas companies to reduce both emissions and transition risk is to cut the production of fossil fuel products. Those companies with climate goals reliant on the widespread deployment of CCUS and NETs are placing at best a risky bet.”