For more than 20 years they told us that our knowledge, our abilities and our labour were not wanted, were not needed, and were not part of the future. In fact, they said our occupation is morally wrong and that they wished we didn’t exist and had never existed. All that came to an end when the German government admitted that it needs its last remaining nuclear power plants. A new social contract for nuclear energy is about to be written and industry needs to get involved.

It is no wonder that the nuclear industry quietly despised Germany’s phase-out policy and its most enthusiastic cheerleaders, but it doesn’t give me any pleasure to write that the glossy bubble of a renewables-only future has burst. While wind and solar are brilliant ways to use less fossil fuel, as variable sources they can never replace it (or nuclear) completely – at least not without an as-yet non-existent ecosystem of batteries, hydrogen and demand-side response. In practice, fossil fuels capitalised on the shift towards renewables to embed themselves as essential back-up capacity, often replacing nuclear plants that have been pushed out markets that were designed for the benefit of renewable developers.

In Germany’s case, one question we asked was always, “What if Putin turns off the gas?” but we had that the wrong way around. The problem actually arose in February when Germany went to turn off the gas but found it couldn’t afford to. Now at the time of writing, Putin has indeed reduced gas flows significantly and all of Europe is bracing itself for a real shut off this winter.

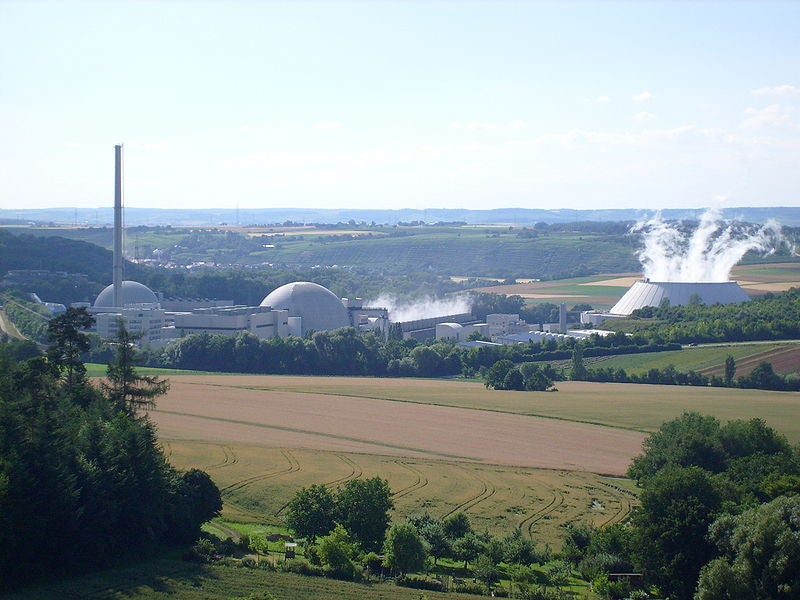

In this deadly, economy-killing scenario, simply allowing its last three nuclear power reactors to keep operating was always the option with the highest yield for the lowest cost available to Germany. Sure, nuclear only offsets a few percent of gas consumption within Germany, but every bit counts in a war effort with energy security impacts across all of its borders. Even if Germany might not have a market need for the additional electricity, its neighbours would happily import it.

Chancellor Olaf Scholz’ government put itself on a path to losing its credibility by claiming the remaining nuclear power plants faced insurmountable challenges in terms of licensing, inspections and fuelling. These statements were no reflection of the true reality. One of the worst things a leader can do in a crisis is leave important decisions to the last minute but Scholz and his cabinet did just this. PreussenElektra, the owner of the Isar plant, wrote to the government permission to operate for longer back in early March, which indicates it only took about three weeks to assess the situation and find that longer operation was feasible. However, the offer was ignored by the Green-controlled energy ministry which wouldn’t let go of its dream to kill nuclear power. Statements of feasibility from the trade association Kerntechnik Deutschland as well as technical support organisation TÜV were dismissed.

However, the government wasn’t persuaded by any of nuclear’s technical arguments or its excellent operational record. It was the cold hard facts of energy security being explained by newspapers, scientists, and business leaders behind the scenes. It is sad that too many of those experts and journalists had kept their mouths shut for years as Germany slept-walked into this situation, so enormous credit must go to the dogged grassroots campaigners who worked to save German nuclear even when the owners of the plants had given up. The industry truly doesn’t deserve them.

So where are we now? For me the key thing is that Germany’s political class has officially admitted that nuclear power works and is not some awkward anachronism. It has admitted that the phase out of nuclear is no free ride. It has had costs in terms of sovereignty, national pride, and potentially even lives. This is all so far above and beyond the navel-gazing of waste disposal debates and so on – which had been given as major reasons to phase out nuclear – that the case against nuclear has been torpedoed below the waterline.

Furthermore, a poll in Die Welt newspaper showed that 82% of Germans would favour keeping nuclear, with that split evenly between getting through the current crisis and into the long term. Even among Green supporters the total figure for support is 68%, according to this survey. The German people are not anti-nuclear, so why should their government be?

At the time of writing, it seems certain that the remaining reactors Isar 2, Emsland and Neckarwestheim 2 will be legally enabled to continue operation for a limited time at least. It’s also possible that the last three to close, Brokdorf, Grohnde and Gundremmingen C will be brought back into operation. The principles proven here mean that Scholz and his Green allies would not automatically be successful if they tried to portray this as just a temporary measure.

This historic turning point for the nuclear sector can and should be given some more momentum, but let us first take a moment for reflection. Many across the nuclear industry have been critical of Greens’ pursuit of nuclear shutdown and its unintended consequences. It’s easy to see them as irresponsible, arrogant or even stupid. But let us remember they are not stupid, but they are very principled. We need to show Germany and the countries it influences what nuclear is really all about, what its people are really like, and what really motivates them.

There must be a new conversation about Germany’s relationship with nuclear energy. It is great that there are many in the political sphere who will want to collaborate on this, but do not wait for this to be started by the authorities and institutes set up and funded by decades of green policy. It is industry’s own responsibility to create this new conversation.

There is official recognition that nuclear energy is low-carbon, it is sustainable and it has an important role to play. This is the conclusion of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the International Energy Agency and the United Nations Economic Council for Europe, as well as the European Commission. The experience is in: renewables help us use less fossil fuels, but cannot eliminate them completely with current technology. The need is urgent: For security and for the environment we have to urgently evict fossil fuels from their central position in the economy.

There is official recognition that society does need our knowledge, our abilities and our labour. We must activate those and showcase them as a service to society. And where do they reside? In the people of the industry. It was clear after the COP26 conference last November that the data was already settled and only emotional arguments against nuclear could remain: Let us meet those arguments on equal terms by representing ourselves through the human stories and experiences of the workers, scientists, experts and communities of nuclear energy. If the answer to hate is humanity then let’s show the true face of nuclear in Germany – the human face of a competent, skilled and principled sector that works hard for common values of a strong economy in a secure country with a clean environment.

This is the dawn of a new social contract for nuclear in Germany and throughout all the countries it has influenced against nuclear, but the industry can’t complacently expect this to develop on its own. It has to invest today in showing its true face once again.

This article first appeared in Nuclear Engineering International magazine.