In 2023, UKAEA published an open call on the UK government’s tender portal, asking to receive input from the market on “the capabilities that artificial intelligence, virtual reality and other automation could offer in enabling real-time reporting using innovative visualisation technology”. UKAEA said it was “particularly interested to understand where disruptive technologies have been used in other industries that could be applied to the field of nuclear”.

The call comes at a time when the UK’s energy industry is in the middle of a digital transformation. The country’s energy networks and energy asset owners have been pressed to make that digital transformation by industry regulators and by government, who warn that without moving to a digital environment the current revolution in the nature of the industry’s assets – from a few large power stations to millions of installations ranging from a few kilowatts for a household to multi gigawatt fission and fusion reactors – will not be achievable. But those bodies are pushing at an open door. The energy industry also sees a huge opportunity in digitalisation to save costs and streamline operations, in which tools such as ‘digital twins’ of their assets, will enable them to develop and train operators or test new ways of using assets in a virtual environment, before taking on the higher costs and risks of acting in the real world.

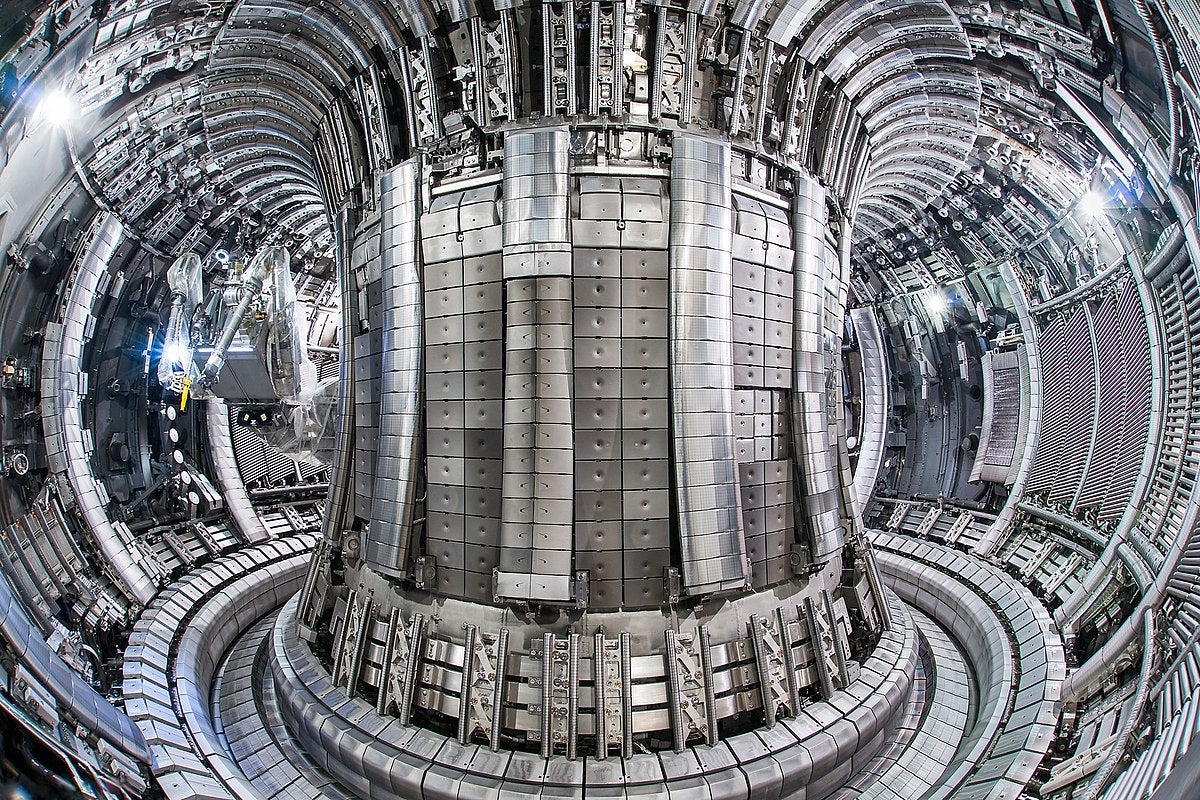

As a centre for future fusion power UKAEA at Culham has to take the same digital leap as the rest of the power sector. At the same time, it has long-lived assets now moving into the end-of-life phase – primarily the Joint European Torus (JET), which finishes its science mission at the end of the year.

As its call to the market illustrates, its embrace of the digital opportunity is equally important for both these activities. But, as Rob Buckingham makes it clear, digital-enabled nuclear industries may change nuclear’s interaction with other sectors and could help it dispel its reputation as a closed shop.

Disruption or innovation

Buckingham is executive director at UKAEA and he heads the robotics division, RACE (Remote Applications in Challenging Environments). He is also now responsible for JET Decommissioning and Repurposing.

Talking about the organisation’s open call, Buckingham quickly opens up the definition of ‘disruption’. He says, “People love innovation, and they don’t like disruption.

But of course, they are the same thing. Innovation causes disruption.” He is looking for change that can be tested and scaled up and that “will disrupt the way we do things”.

Talking about gearing up to decommission JET Buckingham notes that there are many sectors that will require complex decommissioning processes, whether they are under the sea, in space or onshore assets that are inaccessible, such as nuclear reactors. He says dealing with those externalities should be part of the engineer’s job from the start.

His organisation works closely with the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA), which is tasked by the government to clean up the UK’s 17 earliest nuclear sites, but UKAEA’s focus on fusion gives it a different challenge.

He says, “We know from nature you never get something completely free… there are always consequences and we should have our eyes open.” The fuel for JET and its successors is deuterium and tritium; the tritium is radioactive and as it migrates “we end up with tritiated materials. How we manage that and extract the tritium is really important. Then there are other materials activated by the neutrons from fusion. None are long-lived but they have to be managed.” Management is not just disposal: it includes reducing the hazardous waste elements, reuse and recycling.

Part of innovation and disruption – and UKAEA’s call to the market – is learning from other industries. To lay the foundation for this, Buckingham explains that a huge amount of effort went into demonstrating to the UK government that fusion is different from the fission industry, with different hazards, so that, rather than being regulated by the Office for Nuclear Regulation, it could be overseen by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and Environment Agency (EA) – regulators familiar to other industries. That argument made, the risks and hazards of the industry can largely be considered in a similar way to other industries.

“That gives you a chance to learn from other people” and prompts new ways of looking at the problem, Buckingham says. For example, “There is an interesting question as to whether it [fusion] is a process industry that has radioactive waste or the opposite. Your starting point in the approach to dealing with waste is important.”

He has taken on the responsibility of JET Decommissioning and Repurposing because of this opportunity and because it is “the first opportunity to look at decommissioning a fusion power plant for a long time and the first one for another 50 years or so, so it is a really important learning opportunity. So rather than thinking of just getting rid of it, let’s do some thinking about what technologies are out there in this industry and what we can do”.

The digital future

As noted above, JET is moving into the decommissioning phase at a time when many companies – including those in the energy sector – are taking advantage of new digital opportunities to build ‘digital twins’ of their assets.

Buckingham details some of the opportunities and benefits of such digital twins. They enable planning and strategy, because the virtual environment allows you to share a view of the world. They provide a platform which allows for faster training, testing and decision-making and for planning and rehearsing specific operations, “Because you are not limited to hardware”. And with all the data available within the digital environment that allow an asset owner and operator to ‘scroll back’ what happened in the past and ‘scroll forward’ to imagine and test potential procedures or strategies.

Talking about using these digital tools at UKAEA, Buckingham says, “JET has always had good models of the inside of the reactor and used them to plan. We can include images of what it looks like – including robots and robots moving in real-time. We are adding in other information like radiation maps, which provide augmented reality. We are also adding force because we have ‘person in the loop’ machines and haptics [which replicate ‘feel’]. If you handle a component, you can feel the forces involved.”

These digital ways of working are not unique to the fusion industry – in fact much of the software has more in common with process industries and with consumer uses such as gaming, than with traditional nuclear engineering. In part, UKAEA’s engagement with the market aims to tap these sectors’ experience and tools.

Buckingham says previously nuclear has “fished in a fairly small pond,” but now, “The nuclear sector needs to reach out to those working in the games sector and all the others to keep up with what is going on and then apply the useful bits that work in our environment and within our regulations”. He says it would be foolish – expensive and slow – for the industry to try re-create for itself solutions that are used elsewhere. “The games engines we use are software products being used in sectors like automotive, aerospace etc – generic tools and control systems. It is only when you get to machines in specific environments with specific hazards that you get particular.”

In practice, to get the best out of new entrants Buckingham says, “You have to give them some context”. It is important not to be too generic in talking to companies previously outside the nuclear industry and wasting development time for both parties, and equally important not to be too nuclear-specific at an early stage and miss out on options that could be adapted to the industry’s needs.

One of his examples is the LongOps initiative, a £12 million (US$15.3 million), four-year nuclear industry collaboration funded by UKRI, NDA and TEPCO, and led by UKAEA’s RACE team. He explains, “We are all interested in using digital twins. One condition of the programme was to put 50% of the money into the supply chain and we went out to ask whether they had relevant technologies in these areas and could contribute. We have had a great uptake from a bunch of companies and it has been brilliant to see what companies bring to the table.” He says 80% of the participants are companies familiar to the industry but 20% are new companies with new thinking, for example there is one company that has been developing haptic systems for surgery for a number of years. Buckingham says they are working closely with this company “and hopefully we will get the benefit as they improve their product”.

Opening the doors

Looking ahead, Buckingham says there is a “digital layer to the world now” and all the digital twins will start to come together, such as in complex city models that include transport, buildings, etc. For him, that is a parallel to complex nuclear sites and he says, “I think we will get to the point where we will have very detailed digital replicas of a whole plant.

“Linking this back to hazards, I firmly believe a fusion power plant will have to be operated remotely, in which case the digital model is important. You still have people doing the operation but it will be hands off and with lots of planning before you use the real tools.” That fits with some of the operating models for small modular reactors and already it is used to manage other assets in the power system, such as battery arrays, wind and solar farms, or complex mixes of several assets. Again, there is experience to be exchanged with other sectors. Buckingham says, “UKRI had a programme called Robots for a Safer World, targeting industries where it makes more sense to have the people remote. The areas were offshore, space, mining and nuclear.”

The outcomes include digital services that allow people to be upskilled so they are using digital tools, either to complete a task or to learn it so that they can be more productive, safer and faster when they move into the real environment. “There are some parallels between nuclear workers and miners. They are both going into hazardous environments where protective equipment is needed. If you can avoid sending people into hazardous places but you can still enable them to do the work then there are opportunities. To make the tools, to operate them, to plan how to use the tools work better – these are opportunities to disrupt the model,” says Buckingham.

The digitally-enabled world will have to plan in much more resilience to change. “All these digital tools will only get better and quite fast. You have to be a bit more adaptive and agile because the tools will change and offer new opportunities. You have to keep up – and plan an obsolescence strategy,” he says.

Surprisingly, one area where Buckingham thinks change will be less dramatic is in the effect of artificial intelligence. He says, “In regulated sectors, we will use these tools as part of planning but then we will put them back in the control of people. All of our controls – law, regulations, insurance – are based on the behaviours of people. We have developed these checks and balances to get consistent performance and good behaviours.” He says the way to manage that is to use these new techniques to identify better ways of doing things. “Once this new knowledge is captured, it will then be used to improve existing processes and techniques”.

Social change

As well as technical change, this digital and robotics-led model is also set to prompt societal changes – both broadly and within a nuclear industry that has in the past often been seen as a ‘closed shop’ for both staff and suppliers.

Buckingham points out the opportunity to develop specialist clusters. Another initiative, the Robotics and AI Collaboration (RAICo) includes NDA, Sellafield, the University of Manchester and UKAEA. It is based in the small town of Whitehaven in Cumbria close to Sellafield for proximity ease. Sellafield is the single largest employer in the area, but, as Buckingham says, “putting digital and AI jobs in Cumbria will create a cluster and give people increased reason to come and stay”. Equally, digital technologies allow for remote working, which provides an alternative for cluster members without having to leave the area.

For specialists in future, there may be more movement between the nuclear industry and other sectors, because of the similarity in digital-specific roles across industries. As Buckingham says, “Everyone thinks their industry is ‘special’ and it is nearly always not true. There are huge numbers of very creative humans all over the place and trying to tap into that creativity is very sensible”.

This article first appeared in Nuclear Engineering International magazine.