Over the past few decades, automation in the mining industry has gradually reduced the role played by the miner in the pit, edging them further and further away from the coalface. Recent breakthroughs in autonomous robotics have promised to take this process to its logical conclusion. Mining Frontiers writer Greg Noone talks to Professor Sebastian Scherer, senior systems scientist at Carnegie Mellon’s Robotics Institute, and John Welborn, managing director and CEO of Resolute Mining, about how long it will be before humans are eliminated entirely from the physical side of mineral extraction.

Just under 7,000 people visit the Tour-Ed Mine & Museum in Tarentum, Pennsylvania, every year.

First opened in the 1850s as a coal pit, the site is now one of the state’s more niche tourist attractions, open to visitors keen to experience first hand the life of a haulier. Activities include live demonstrations of the equipment used by 19th-century miners, a short trip on a specially-adapted mine car, and a brief, disorienting submergence in complete darkness when the lights are switched off by your guide.

The site remains, as Tour-Ed’s website puts it, one of the “coalest” attractions you can visit north of Pittsburgh.

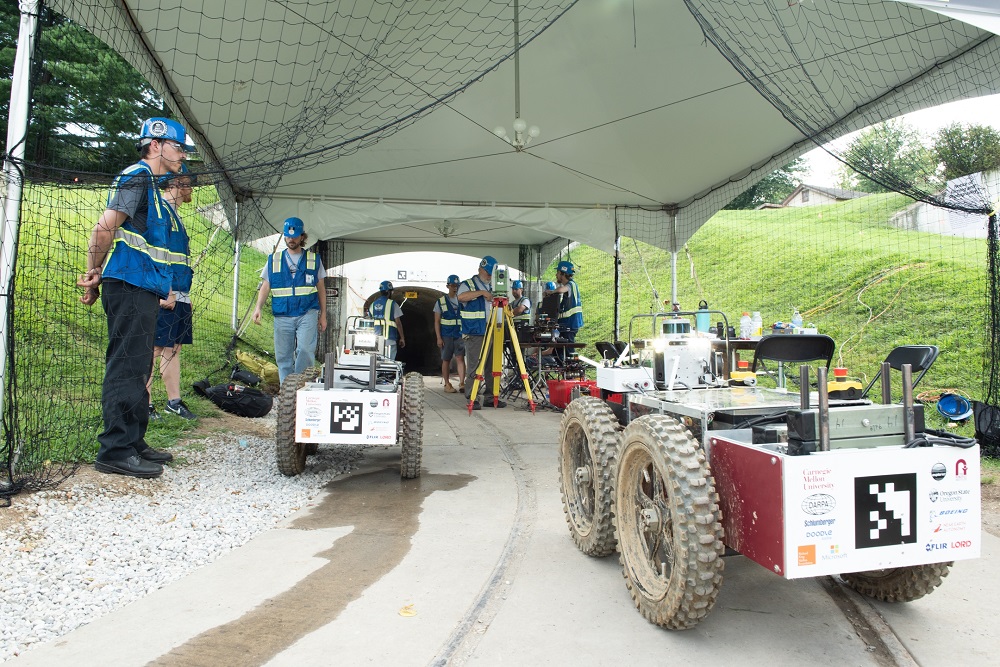

Visitors to the mine last summer, though, might have heard an unfamiliar whirring echoing down its old tunnels. Those curious enough to follow the sounds to their source would have found members of Team Explorer, a group of engineers from Carnegie Mellon University, busy testing the capabilities of several autonomous aerial and ground drones.

“We would start at 12 noon to go in the mine, stay until 8pm, come back, debrief at 9pm at the university, and fix the parts and repeat that cycle for a month,” recalls Professor Sebastian Scherer, a senior systems scientist at Carnegie Mellon’s Robotics Institute.

DARPA automation research has ‘obvious implications’ for mining industry

Tour-Ed is located only 25 minutes by road from its main campus, and the engineers from the university found it to be the perfect test site for their drones, before being put through their paces in the DARPA Subterranean Challenge at the Edgar Experimental Mine in Colorado.

The competition, which held its tunnel circuit in August, is intended to “solve one of the most intractable problems when it comes to operating robots in underground environments” – namely, how to get them to solve problems when communication with their operators becomes impossible.

“Once you make a turn, it doesn’t really matter that much what kind of radio you have, just because there’s a lot of rock,” explains Scherer. “There are some really low frequency [radios] that can communicate, but the amount of information we can get through […] is so little that they’re not useful.”

The tunnel circuit, therefore, was a call to arms for the best and brightest robotics engineers in the US to build machines capable of solving challenges autonomously – namely, locating artefacts within a mine while communicating what it found, and where, back to its operators. Team Explorer attempted to circumvent this problem by designing its unit to drop Wi-Fi nodes behind it, slowly establishing a mesh network.

Still, the reliability of this improvised line of communication varied according to where the drone was in the mine, with the signal inevitably dropping in certain places. “And so, the robots have to be aware of how much data they can send and regulate that,” says Scherer.

The engineering insights gleaned from the DARPA Subterranean Challenge are, primarily, intended to produce applications for first responders and soldiers entering complex underground environments cut off from conventional communications channels.

That said, its implications for the mining sector are obvious.

“The problem it’s solving is mapping and finding objects as quickly as possible in a large area,” explains Scherer. Once you solve that problem, adds the professor, a whole host of new applications become possible. “There’s a couple of mining companies that we have been contacted by that are, potentially, interested in this technology.”

Automation could improve safety in the mining industry

Automation is a familiar feature of the contemporary mine. The people who descend into the depths of underground pits no longer carry picks, but operate complex, heavy pneumatic drills, or else ‘continuous miners’ that grind and scrape coal and soft minerals from the wall of the tunnel using sharp metallic teeth. Instead of hauling rocks upon their back in large tarpaulin bags, the assorted rubble and fine particulates of the site are tossed upon conveyer belts and gently carried out to the surface.

Nevertheless, mining remains physically taxing and dirty, not to mention dangerous. According to a report published by the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) on its member companies in 2018, 22 fatalities were recorded in mines in Africa, 17 in the Americas and seven in Asian pits.

Removing human beings from the process, therefore, seems eminently desirable, not only from a cost and time perspective – robots, after all, do not tire or require financial compensation for their labour – but also from a pure safety perspective.

Advances in autonomous robotics have allowed certain sites to make incremental changes in this direction. In 2018, Rio Tinto began operating what the Financial Times described as the ‘first heavy freight driverless rail network’ at its mine in Pilbara, Australia.

The following summer, China’s National Coal Mine Safety Administration announced it was partnering with the country’s leading private space agency to develop “smart” coal-mining robots. Meanwhile, construction equipment giant Caterpillar has recently begun selling autonomous fleets of loaders, dump truckers and bulldozers to interested parties across the sector, something that the company has intended to do since 1985.

Resolute’s Syama gold mine in Mali a case study for full automation

While adoption of this technology should, judging from recent examples, be piecemeal, one site in sub-Saharan Africa has become a useful case study for examining what a fully-automated mine could look like. At the Syama Complex in southern Mali, Resolute Mining has been using automated vehicles and drill equipment almost exclusively to extract gold deposits, to the tune of 300,000 ounces a year.

John Welborn joined the company as its CEO in July 2016. “At that stage, [it] had just completed open pit mining at Syama,” he explains. Resolute had plans to transition to a full underground mine within a few years.

After conducting a feasibility study, and talking to site managers where autonomous systems had been integrated at several stages of the extraction process, the company realised that it would be able to make significant savings on personnel costs and experience an approximate 30% gain in operational efficiency if it designed the new site to be fully automated.

Welborn says that when he is on-site at Syama he will be “looking at our autonomous longhole drill rigs, drilling out tall point blast patterns in the underground mine, and our fleet of autonomous loaders filling the autonomous haul fleet trucks”.

Resolute’s CEO sees four main benefits from total automation at Syama. Safety is the “really obvious one, because we’re taking people out of harm’s way in an underground environment”, explains Welborn, before adding that existing policy mandates no manual interaction with the automated equipment on-site.

The mining process itself has also become notably more efficient, contributing to greater levels of productivity than one would expect at a manned site. Syama’s autonomous longhole drill rigs are a case in point.

“Normally, you’d manually operate them,” says Welborn. “You’d have to design the blast pattern and the associated drill holes, and then they would be manually drilled out using a jumbo drill rig, where the angle and the depth of each hole is effectively judged by the drill operator.

“The autonomous longhole drill rigs that we’ve deployed at Syama locate themselves at the end of the drill point, [and] they sense where the rock is, and then they autonomously drill out an absolutely perfect drill pattern in terms of depth [and] angle, which results in a significantly improved blasting outcome.”

Full automation has also led to another, unexpected benefit. Previously, Resolute relied on expatriate miners who were well trained in drill operation and other technical aspects of mining to be flown in and out of the site.

Those skill sets were thin on the ground in Mali. Simplifying the operation of heavy equipment using more contemporary interfaces, though, means that Resolute can hire workers from much closer to Syama. “We’re finding it a lot easier to train local Malians using high-technology solutions than we have in the 15 years we’ve been operating there in a more manual environment,” Welborn adds.

Blending autonomous and manual processes is a big challenge

If the deployment of autonomous technology in a mine can result in such dramatic improvements, why isn’t it being rolled out in more places? For Welborn, it comes down to the innate difficulty in combining robotic processes with manual ones.

At Syama, “we make sure that there’s no possibility of manual interaction with the automated equipment,” he explains. “I think that’s actually quite a big limitation for our operations, and certainly thinking more broadly about the technology, what we really want is autonomous equipment that can interact seamlessly with non-autonomous, manually-operated equipment.”

That it doesn’t can be attributed to a range of factors. One is the layout of established underground mines, which often have decline tunnels that allow manned haulage trucks to operate with margins of error in the metres, rather than the millimetres achieved by their autonomous counterparts.

Miners also tend to be attitudinally conservative, argues Welborn. They tend to think, he says, that “once you’ve got an operating procedure that’s working, you focus on refining it rather than changing it completely. [It’s] difficult to stop a mine for long enough to implement a new automation programme”.

Nevertheless, Resolute’s CEO is confident the industry will continue to see more and more autonomous vehicles deployed in the sector, albeit at a slower pace than some proponents of the technology might like. “The advantages are just so obvious, from safety to productivity,” he concludes.

This article originally appeared in the winter 2019 edition of World Mining Frontiers. The full issue can be viewed here.