While sectors across the industry grapple with the devastating impact of coronavirus, some clean energy firms have posted strong financial results despite the economic downturn and historic low demand for electricity. Andrew Fawthrop takes a look at why low-carbon energy providers seem to have navigated the crisis in better condition, and how the energy transition debate has bubbled to the surface of the global health emergency.

After a start to the year in which record levels of low global demand for energy products have weighed heavily on the industry, last week provided a glimpse of how the shift to clean power has helped some companies navigate the disruptions caused by coronavirus.

In a flurry of first-quarter updates, the well-documented market challenges that have plagued Big Oil in recent months as a result of the pandemic were laid out in black and white, with balance sheets revealing a series of losses, troubled revenues and rare dividend cuts.

The International Energy Agency (IEA), meanwhile, published a market review in which it highlighted the decline of coal and natural gas in the global energy mix – with demand for both power sources on track to shrink to levels not seen since the last century.

Alongside these gloomy reports, however, came news from clean-energy frontrunners Orsted and Iberdrola that the first three months of 2020 had delivered robust financial performances, despite the operational difficulties presented by Covid-19.

Danish wind power specialist Orsted produced a 33% earnings jump with operating profits just short of $1bn for the three months to March, while Spain’s Iberdrola – a utility giant that has pivoted its business to focus on clean energy – increased its net profit by 5.3% to more than $1bn.

European industry leaders acknowledge long-term importance of clean energy in a post-coronavirus world

Several factors played into this intriguing contrast between clean energy’s fortunes amid the health emergency and those of its counterparts in the fossil fuels industry, serving up a reminder of the prevailing pre-crisis debate – that of the low-carbon energy transition.

“There is complete consensus that the road to economic recovery must be green, with the fight against climate change at its core,” was the outlook from Iberdrola’s chief executive Ignacio Galán as he presented his firm’s results.

It is a sentiment that has been echoed by global energy associations, as well as by European policymakers as they assemble fiscal recovery plans designed to help countries rebuild their economies in the wake of Covid-19.

With the emphasis on incorporating the green transition into the post-pandemic economic roadmap, there is growing long-term pressure building on fossil fuel companies as a smart investment case – even beyond the immediate concerns of low fuel demand and plunging commodity prices brought on by the coronavirus lockdowns.

Royal Dutch Shell boss Ben van Beurden touched on this idea last month, as he announced the oil major’s plans to accelerate its efforts to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

He told investors: “It is about finding the business value in the energy transition and being a world-class investment case, far into the future.

“The biggest long-term question for an oil and gas business like Shell is the question raised by climate change.”

Clean energy has enjoyed priority access to power grids at a time when electricity demand has fallen significantly

A large part of clean energy’s comparative strength during this period of huge economic turmoil has been the fact that electricity grids and utility companies have been required to purchase low-carbon electricity ahead of that generated by fossil fuels.

It is a fact indicative of the increasingly negative sentiment around carbon-heavy energy supplies, and a clear demonstration of the effects that climate-related regulatory interventions can have on industry dynamics.

GlobalData’s senior power analyst Somik Das says: “Declining power demand and negative electricity prices have hit fossil fuel-based generation the most because in most electricity systems grid operators are obliged to buy clean energy first.

“In developed markets, the ongoing drop in electricity demand combined with the drop in gas prices has led to the closure of coal-based generation plants. For instance, the UK has been catering to its electricity demand without any coal-based generation for a continuous 20 days.

“Because of the lack of demand, fossil-fuel focused businesses could not stimulate investments when compared to the clean-energy focused companies.”

This priority access to finance at a time when capital budgets are being squeezed across the energy industry has offered a huge boost to renewable power companies, enabling them to maintain important liquidity in their operations and convince investors of the relative safety of clean assets compared to fossil fuels.

“Carrying out investments and maintaining liquidity have played important roles in ensuring the better performance of both Iberdrola and Orsted during the crisis,” adds Das.

“These companies are maintaining liquidity to manage the impact of deferred payments and to keep their operational and construction activities on track. Even with disruption in supply chain, neither expect delays in their under-construction projects.

“They are securing supply and also accelerating purchases to help their suppliers generate cash flows.

“Renewable energy offers sustainable growth and is better positioned to deal with the economic impacts of Covid-19.”

IEA says global energy industry will never be the same again

At the same time as these financial updates were filtering through last week, the IEA delivered its prognosis of the state of a global energy industry that has been ravaged by coronavirus, identifying the “biggest shock” to the market in more than 70 years.

Discussing the outlook, the energy watchdog’s executive director Dr Fatih Birol notes that “only renewables are holding up during the previously unheard-of slump in electricity use”.

“It is still too early to determine the longer-term impacts, but the energy industry that emerges from this crisis will be significantly different from the one that came before,” he says.

While low-carbon electricity sources are expected to increase their share this year, accounting for around 40% of the annual global energy mix, coal and natural gas are becoming “increasingly squeezed between low overall power demand and increasing output from renewables”, according to the agency.

Renewable energy is now competing with fossil fuels on price

The prioritisation of clean energy sources across power grids has certainly played into the success of low-carbon producers during the coronavirus outbreak, but so too has the continued decline in the cost of renewables as the advantages of scale kick in.

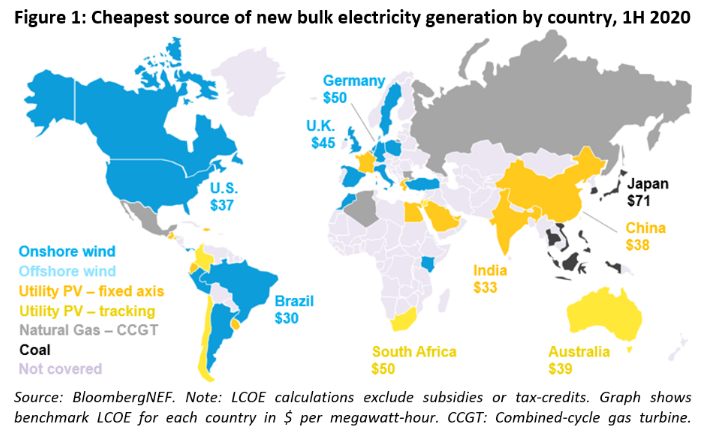

Research published recently by BloombergNEF (BNEF) highlights the increasing cost pressures now facing coal and gas, as renewables compete on price in key markets around the world – with solar photovoltaic (PV) and onshore wind now the cheapest sources of new-build power generation for at least two-thirds of the global population.

According to the update, the levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) for onshore wind and utility-scale solar PV has decreased by 9% and 4% respectively since 2019 – standing at $44 per megawatt-hour (MWh) and $50 per MWh.

This downward trend has been largely attributed to the bigger scale of new renewable projects in recent years, although the major disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic will inevitably muddy the waters of any future projections.

BNEF’s chief economist Seb Henbest says: “The coronavirus will have a range of impacts on the relative cost of fossil and renewable electricity. One important question is what happens to the costs of finance over the short- and medium-term.

“Another concerns commodity prices – coal and gas prices have weakened on world markets. If sustained, this could help shield fossil fuel generation for a while from the cost onslaught from renewables.”