Growth in global coal demand will stall over the next five years as the appetite for the fuel wanes and other energy sources gain ground, according to the latest coal forecast from the International Energy Agency.

Coal demand in 2016 will be below 2013 levels, confirming a new trajectory since the meagre growth in 2014 after more than a decade of 4% annual growth. In 2015, global coal consumption decreased for the first time in this century. The big decline in China and the United States was not offset by growth in India, Indonesia, the Russian Federation and Vietnam. In China, coal use declined in the major consuming sectors: electricity, steel and cement. Coal generation dropped, driven by a sluggish 0.5% electricity demand growth and the diversification policy, which led to growth in hydro, nuclear, wind, solar and natural gas power generation. In the United States, coal power generation plummeted as a result of low natural gas prices and coal plant retirements pushed by Mercury and Air Toxics Standards legislation; hence, coal consumption dropped by 15%, the largest annual decline ever, to levels not seen in more than 30 years.

Coal burn greater than ever

Except for the 1920s and the 1990s, coal use in the world has been continuously increasing since the start of the Industrial Revolution. Now we are witnessing another halt, but, despite this, if we consider coal consumption from a historical perspective, the world has never burned so much coal.

IEA’s forecast shows a slight increase after a few years of decrease, reaching 2014 levels only in 2021. Given the growth in primary energy globally, this means that 2011 will likely turn out to have been the peak for coal’s share in the energy mix in this century.

Power generation

While coal will continue to be the preferred source of power generation, the share will decline from over 41% in 2013 to around 36% in 2021, driven by lower demand from China and the USA, along with fast growth of renewables and strong focus on energy efficiency.

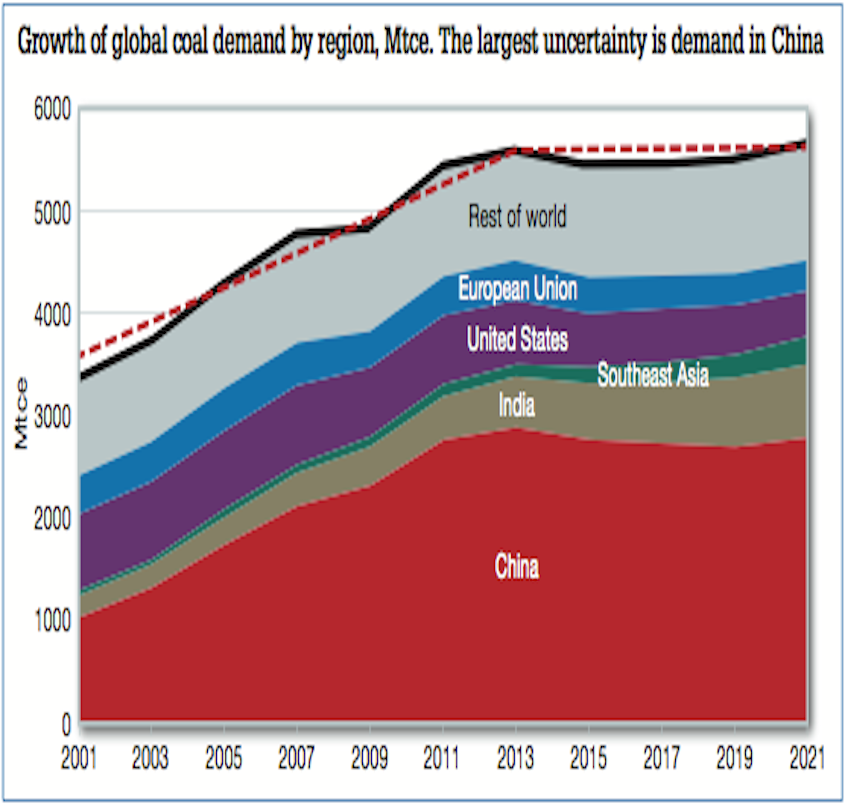

But, as an indicator of coal’s paradoxical position, the world is still highly dependent on coal. The demand curve showing near term lower demand and then recovery by 2021 to 2014 levels depends greatly on the trajectory of China’s demand, which accounts for 50% of global coal demand – and almost half of coal production – and more than any other country influences global coal prices.

Geographic shift

The new report highlights the continuation of a major geographic shift in the global coal market towards Asia. In 2000, about half of coal demand was in Europe and North America, while Asia accounted for less than half. By 2015, Asia accounted for almost three-quarters of coal demand, while coal consumption in Europe and North America had declined sharply below one quarter. This shift will accelerate in the next years, according to the IEA.

The end for coal? Not yet

Because it is relatively cheap and widely available, coal remains the world’s number one fuel for generating electricity, producing steel and making cement. It provides almost 30% of the world’s primary energy, declining to 27% by 2021. However it is also responsible for 45% of all energy-related carbon emissions and is a significant contributor to other types of pollution.

“Because of the implications for air quality and carbon emissions, coal has come under fire in recent years, but it is too early to say that this is the end for coal,” said Keisuke Sadamori, the director of the IEA’s energy markets and security directorate. “Coal demand is moving to Asia, where emerging economies with growing populations are seeking affordable and secure energy sources to power their economies. This is the contradiction of coal – while it can provide essential new power generation, it can also lock-in large amounts of carbon emissions for decades to come.”

China’s dominance

The IEA’s report acknowledges China’s continued dominance in global coal markets. Coal-fired power generation in China dropped in 2015 due to sluggish power demand and a diversification policy that led to the development of new renewable and nuclear power generation capacity. The IEA forecast for Chinese coal demand shows a very slow decline, with chemicals being the only sector in which coal demand will grow, reaching 2816 Mtce by 2021, around 100 Mtce less than the 2013 peak.

In the United States, coal consumption dropped by 15% in 2015, precipitated by competition from cheap natural gas, cheaper renewable power – notably wind – and regulations to reduce air pollutants that led to coal plant retirements. This was the largest annual decline ever, reaching levels not seen in more than three decades. Another substantial decline is expected in 2016. Looking ahead, the IEA forecasts a 1.6% per year decline, much slower than 6.2% decline over the past five years, as higher gas prices result in less coal-to-gas switching.

The brightest sign for coal was a recent unexpected boost in prices that provided relief to the industry. After a sustained four-year long decline, coal prices rebounded in 2016, mostly because of policy changes in China to cut capacity and curb oversupply. This was another example of the strong influence of macroeconomic developments and policies in China in shaping the global coal market.

Future of CCS

The report emphasises that despite the Paris Climate Agreement and a clear need to reduce the impact of coal burning there is apparently no effective impetus to promote the development of carbon capture and storage technology. In fulfilling the goals of the Agreement, says IEA, CCS will be a key factor, as the Agreement establishes more ambitious temperature targets while providing a framework for climate action that extends beyond 2050, namely to achieve a balance between man-made emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of the century.

This should provide momentum for refocusing efforts on CCS. Yet, one year on from Paris there is little indication that governments are acting to enforce limits on CO2 emissions that will allow investment in CCS to happen. Without CCS or technological innovation to use captured CO2 for commercial purposes, coal must be virtually eliminated if Paris targets are to be met, which will be challenging in power generation and even more so in industrial applications.