Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions must be controlled to have any chance of meeting the Paris Agreement goals. A complicating factor is that controlling carbon dioxide from fossil fuel combustion presents a conundrum for a developing nation such as India.

Being the second most highly populated country in the world and having the third largest and fastest-growing economy, India craves massive amounts of energy, which mainly comes from fossil fuel combustion, particularly coal.

Despite its reliance on coal, India’s GHG emissions are a mere 2 tonnes/capita, compared with over 7.3 tonnes for China and 15.5 tonnes for the USA. The size of the population means that India is the third-largest total emitter, contributing 7% to total GHG emissions, after China’s 28% and the USA’s 14%.

Besides the international pressure to control GHG emissions, India is also potentially very vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. This combination means that India has started driving its policy onto a sustainable path, unlike in the past when it used to claim that flexibility on emissions was needed to afford it equal growth opportunities to those enjoyed by developed countries. The proactive policies and initiatives India announced and adopted in recent years have been impressive – such as the massive solar power capacity build-up and the recent “Panchamrit” announcement at COP-26 in Glasgow. A major shift towards cleaner and greener energy while phasing-down coal-based power is one of the key initiatives.

But India’s shift from coal-based power will not be rapid, due to the sheer scale of the challenge, the large share of coal in the energy mix, the lack of available alternatives, the long lead times, and the investment needed.

India’s total installed generating capacity is almost 400 GW, with 59% from fossil fuel and 41% from renewables and nuclear. Coal-based power is the largest single energy source, accounting for some 51% of capacity. In terms of actual generation, coal produces 75% of the annual total (1400 billion kWh currently). This power generation consumes over 700 million tonnes of coal per year, representing over 88% of India’s total coal consumption and around 90% of domestic production. The journey towards renewables that India has started – from 40 GW of renewables capacity in 2020 to 100 GW in 2022 and the target of 400 GW by 2030 – is extremely ambitious. However, coal-based power is expected to remain an important energy source for decades.

A study by the International Centre for Sustainable Carbon (ICSC) has found that increased electricity demand in India is inevitable as it continues rapid economic development and that coal-based power will constitute a significant part of total generating capacity for some time, even as the country increases its renewables capacity. This means improving the existing coal-fired power sector is more urgent – through improved efficiency, tighter environmental controls, and better pollution monitoring and reporting.

ICSC’s new study, Status of continuous emission monitoring systems at coal-fired power plants in India, published in December 2021, aims to assist in bringing about these improvements. The study is part of a US Department of State project aimed at “capacity building” in India in the area of emissions reduction and the meeting of tighter emissions standards, or norms, in the coal-based power sector.

Achieving a non-fossil generating capacity of 500 GW by 2030. 2. Meeting 50% of India’s energy requirements from renewables by 2030. 3. Reducing total projected carbon emissions by one billion tonnes between now and 2030. 4. Reducing the carbon intensity of the Indian economy by more than 45% by 2030. 5. Achieving a “net-zero” target by 2070.

The report assesses the environmental performance and status of regulatory compliance at Indian coal-based power plants and suggests a way forward.

New norms: dragged, diluted, delayed

As well as being one of the largest emitters of GHG, Indian coal-based power is also one of the biggest polluters in the country, contributing around 60% of the total particulate matter (PM), 45% of the SO2, 30 per cent of the NOX, and over 80% of mercury emissions produced by Indian industry as a whole. It consumes large volumes of water, has a significant potential for water pollution and results in considerable waste production. Inferior technology, low efficiency, and ineffective pollution control, especially in the case of older plants, are contributory factors, as is the fundamental problem of low-quality domestic coal, containing up to 40% ash, 0.4–0.6% sulphur and 0.01–1.5 ppm of mercury, which inherently constrains power plant performance.

The fast pace of coal plant capacity addition, undoubtedly multiplying the potential for increased pollution, compelled India to revise its coal plant emission limits. The table below summarises the new requirements. In 2015, limits were introduced for SO2, NOx and mercury emissions for the first time and the existing PM emission limit was tightened. Power plants were expected to comply with the new norms by applying suitable measures, such as ESP upgrade, FGD installation, SNCR, SCR and/or combustion modifications for NOx control, with the combined effects of these measures acting to reduce mercury emissions. To reduce water use, plants with once-through cooling were asked to adopt cooling tower based closed-loop cooling.

Notification of these new environmental norms was given by India’s Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change (MOEFCC) in December 2015, with a two-year time frame for compliance. Unfortunately, the lack of consultation, planning and timely follow-up by the government dealt a severe blow to this initiative and, as the deadline approached, the new rules became embroiled in rounds of debate and delaying and derailing tactics by the industry lobby – so much so that the new norms have yet to be widely implemented.

The push-back primarily focused on concerns about the investment needed for new technologies, technology suitability and availability, and timelines. Meanwhile, environmental pollution and related health implications across the country were becoming critical, and public concerns generated mounting pressure.

A study published by the Health Effects Institute (HEI) in 2018 estimated that over $33 billion of investment in pollution control equipment was needed for the new emissions limits to be met by 2030. It is also estimated over 1.1 million deaths in India were attributable to PM2.5 air pollution, including 90,000 deaths in 2015 arising from emissions from coal-fired power plants. The study warned that non-compliance with the new emission limits could contribute to 300,000–320,000 premature deaths and around 50 million hospitalisations between 2019 and 2030. Compliance, on the other hand, could provide monetised health benefits amounting to over $129 billion by 2030, assuming the emission limits were met by 2025.

In January 2019, India’s National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) announced a reduction target of 20% for PM2.5 and 30% for PM10 in ambient air by 2024 relative to 2017 as the base year, with the contribution of the coal-fired power sector, thanks to the new limits, expected to be significant. Unfortunately, this was not to be, and the new norms did not help.

The new emissions limits notified in December 2015 were supposed to be met by December 2017. India’s Ministry of Power (MOP) formed a committee in 2016 which, in June 2017, recommended a stage-wise compliance plan for the PM and SO2 limits but proposed a relaxation of the NOx emission limit to 600 mg/m3. It also pushed the 2017 compliance deadline to 2022; this issue was raised in the Supreme Court of India, seeking a direction from the government to follow previous deadlines. The Environment Pollution (Prevention and Control) Authority (EPCA), a Supreme-Court-appointed committee for pollution control in the Delhi–National Capital Region (dissolved in April 2021), also recommended earlier implementation of the new norms – PM and NOx standards by 2018-19 and the SO2 limit by 2020, without any relaxation. This was contested by the MOP and the Association of Power Producers.

The coal plant sector has come to accept that compliance with the new PM emission limits can be achieved by upgrading ESPs and that the installation of FGD equipment can deliver compliance with the SO2 norms. But compliance with the new NOx limits was neglected as they were considered unnecessary and too costly.

Raising the issue of domestic coal quality, the MOP, meanwhile, appealed for relaxation of the NOx limit from 300 to 450 mg/m3, which was subsequently notified as to the new standard. An ICSC report (Adams and others, 2021) assessed that a limit of 300 mg/m3 was achievable. Various pilot-scale technology studies jointly carried out by technology providers and India’s leading power producer, NTPC, had allegedly shown this, but various media reports claim that the findings were presented to portray the non-suitability of SCR and SNCR technology to avoid investment and support relaxation of the norms.

In July 2018, the Supreme Court of India rebuked the MOEFCC for its inability to enforce compliance with the 2015 standards. The MOEFCC, the MOP, and the CEA asked the Supreme Court for a further extension to December 2024, pointing to the inability of power plants to allocate the required capital and operating expenditures within the previous time frame, as well as the lack of available space, water, and necessary raw materials. The Supreme Court granted a five-year extension of the deadline to December 2022.

This was not the end of the matter. Since the NOx norms were relaxed and could be met via combustion optimisation, a residual issue for the majority of plants was the need for a large investment in FGD installation.

In January 2021, the MOP proposed a stepwise FGD implementation schedule (to MOEFCC), with priority given to the power plants in the low ambient air quality areas, highlighting considerations such as shortages of equipment available on the market, increasing imports instead of indigenous manufacturing, the price burden on utilities and consumers, and possible loss of opportunities to develop national resources and foster Indian skilled manpower. This stepwise FGD implementation timetable based on the categorisation of power plants was adopted in 2021, pushing the compliance deadline from December 2022 to December 2025.

Although a CEA report, Review report on SO2 norms, 2021, mentions the idea of pushing the deadline to 2034, at the time of writing, the deadline for compliance with the new limits of December 2025 remains in force.

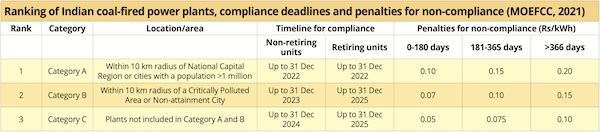

Indian coal-fired power plants have been ranked according to their proximity to populated areas and polluted regions and placed into one of three categories, A, B and C. They have been allotted new deadlines, with penalties for failure to comply.

Under these rules, the penalties for non-compliance range from Rs 0.05 to 0.20 per unit of electricity produced. A non-compliant 500 MW plant operating at 60% capacity would need to pay Rs 32.84 crore (about $4 million at the current conversion rate) per year. Over the same period, this plant would generate around 2628 GWh of electricity, earning it around Rs 1427 crore (about $184 million at the current conversion rate) at a power price of Rs 5.43 per kWh.

Unwillingness to comply

The Indian power generation sector’s unwillingness to meet new standards was evident from day one. The position of “not doable” in the beginning changed to concerns about cost, technology, and timelines, influenced by public pressure, judicial intervention, and global attention. Undoubtedly, the challenges arising from the scale of the investment required, technology suitability and availability, and the short timelines were genuine, but compliance was surely achievable had the government been proactive, with timely planning, coordination, and support. This was lacking initially. In time, the coal-fired power generators realised that the new standards could not be derailed completely. Also, the government increased its efforts to make it happen (albeit with significant delays) by making provisions for investment recovery via added tariffs, stretching timelines and promoting pilot-scale technology tests.

Not only was the first deadline of 2017 a failure, but studies also indicate that the revised deadline of 2022 is unlikely to see sufficient compliance.

A 2020 survey by the Centre for Science and Environment, a Delhi based NGO, found that most plants had ESPs installed, and with suitable upgrades, nearly 73% of them could meet the new norms by the 2022 deadline. In contrast, only 20-30% of plants could comply with the new SO2 and NOx limits by the same deadline. While FGD installation issues received attention and could be evaluated, information on NOx control measures was much less readily available. Since the NOx norm was relaxed

to 450 mg/Nm3, most of the plants are expected to opt for combustion optimisation for NOx control and not SCR or SNCR installation. Compliance with the mercury norm has not received much attention as it is not generally considered a problem and, as already mentioned, it is believed that it can be easily met as a co-benefit from the installation of ESP, FGD and SCR.

An ICSC assessment has found that the Indian government’s continued amendments, derogations and delays have compromised the pressure on utilities to comply, making the new standards less effective in achieving the health benefits in a demonstrably cost-effective manner. India, therefore, continues to face a significant task in closing the gap between what it wants to achieve in respect of coal plant emissions reduction and what can be achieved.

Accurate and reliable emissions data for each coal-fired plant is therefore of the utmost importance and, here, correct implementation of real-time pollution monitoring is needed, in place of manipulated, or estimated data, as a basis for sound policymaking and the taking of appropriate corrective actions.

Unfortunately, the status of real-time emissions monitoring at Indian coal-fired power plants is not very encouraging.

Lackadaisical CEMS implementation

Real-time pollution monitoring was mandated first in February 2014, with the installation of continuous emission monitoring systems (CEMS) for air pollution monitoring and continuous effluent quality monitoring systems (CEQMS) for water pollution monitoring in 17 industries identified as major polluters, coal-fired power generation being one of them. The mandate was later extended to more industries, expanding the real-time monitoring market in India to over $ 800-900 million currently and involving most of the world’s leading technology providers.

Real-time monitoring, which has been practised in the USA and EU over the last 40-50 years, has proven its ability to deliver such advantages as credibility, accuracy, timely control, improved process optimisation and self-monitoring benefits; unfortunately, is yet to be properly realised in India.

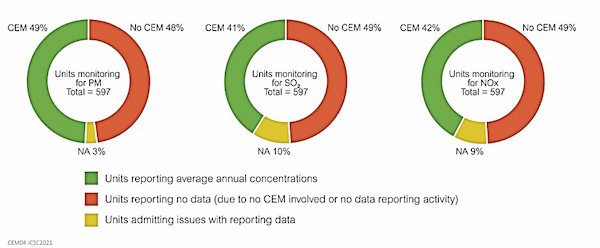

ICSC assessed the CEMS data from the Indian coal-based power plant fleet for the year 2020-21 (Figure 1). The findings were disappointing. Even though almost all the coal-fired power plants have installed CEMS, only half of them were sending regular data to the CPCB (Central Pollution Control Board) and SPCBs (State Pollution Control Boards) and the data quality was low. Most of the non-reporting (despite a minimum 85% data reporting requirement) is attributable to CEMS not being in use, CEMS being out of order or under maintenance, plant under maintenance and connectivity problems. Though the non-reporting plants regularly receive notifications from the system and intermittent enquiries from the regulators, the absence of legal enforcement does not encourage plants to abide by the regulations.

ICSC’s deep-dive uncovered some fundamental challenges: missing quality assurance and quality control systems; missing third party testing and quality control provisions; inherent implementation challenges in the plants; and lack of required skills and knowledge.

Broadly speaking, there are two basic approaches to CEMS quality assurance and control, the heart of effective real-time monitoring:

• the EU type regime, which allows only certified CEMS to be installed for quality assurance, followed by a system of quality assurance levels (QALs) for quality control; and

• the USA type approach, which permits non-certified systems but requires a series of performance tests during installation followed by periodical quality control tests.

India chose to have a hybrid of both approaches but failed to create the required infrastructure. In addition, the delay in publishing the guidance manual and continuing lack of required knowledge and skills among the stakeholders created many problems – ranging from selecting incorrect technology to faulty installation, incorrect set-up, missing data validation and standardisation and data tampering.

Figure 2 summarises some of the main CEMS implementation challenges in India.

Except for big corporates that can afford a sizable skilled technical in-house team, the Indian coal-fired generation industry largely depends on technology vendors for maintenance and troubleshooting and, unfortunately, most of the vendors’ ground-level employees themselves need good training and capacity building, as do the power plant operators and regulators.

A lack of transparency has been another barrier to obtaining the full benefits of real-time monitoring in India. Low confidence in the data compels both the CPCB and respective SPCBs to find excuses and seek various ways to evade making data available to the public. The lack of public scrutiny has not helped and has kept the government from using the CEMS data for checking legal compliance. Only a very few SPCBs, including Madhya Pradesh Pollution Control Board (MPPCB) and Odisha Pollution Control Board (OSPCB), have made efforts to publish the CEMS data. The majority remains reluctant.

Indigenous innovation

On the plus side, experience with data quality problems across various sectors has led India to indigenously develop some interesting innovations in the area of real-time emissions monitoring. Highly automated and sophisticated data acquisition and handling and the practice of remote calibration are particularly noteworthy.

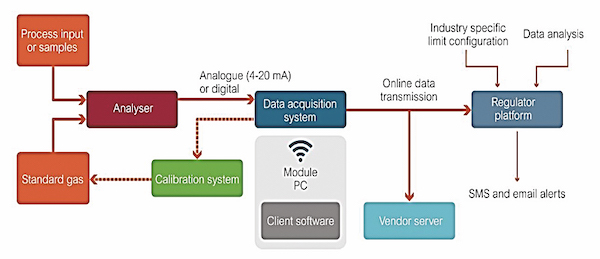

The indigenously developed advanced CEMS data acquisition and handling system, shown in Figure 3, allows direct data transfer from all the monitors, through the internet of things (IoT) and data logger, in parallel to the central server of CPCB and respective SPCBs without any intermediate device, thus avoiding any potential tampering. With the required authorisation, industry, regulators, and relevant stakeholders can access the real-time data, online, anywhere and anytime. The system provides a customised facility to carry out analysis, produce reports, generate alarms, and record calibration and maintenance events with history backup.

The remote calibration system for gaseous CEMS (see Figure 4) is another key innovation that the CPCB or respective SPCBs can use when they observe repeated abnormal data from any industry that they monitor. Using this system, a regulator can randomly choose to remotely trigger a zero and span drift test and assess the response of gaseous CEMS systems installed in the plants, showing up any failings.

ICSC’s study finds that India’s real-time monitoring technology is a significant initiative toward achieving a better environmental governance system. However, in the absence of some fundamental infrastructure and practices, it remains underutilised. Also, data quality remains poor and not properly assessed in the absence of onsite inspection, regular checks, and actions against defaulters.

Some of the SPCBs, it must be said, do carry out due diligence to an extent, but it is not standard practice. ICSC’s analysis of India’s coal-based power sector makes this apparent.

The need for capacity building

The Indian government needs to fast track the development of an indigenous certification system and a list of approved third-party laboratories for tests and checks. On-site inspection and regular checks, which are part of good practice internationally, can help to resolve present challenges in the system.

Improvement in data quality will build the confidence needed to give real-time data legal status in compliance checks, which requires amendments to the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974, the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981, and the Environmental Protection Act, 1986. Delays and negligence will make the problems persist and may prove costly and delay effective policies supportive of sustainable development.

One essential element is training and capacity building for regulators, plant operators and other stakeholders – throughout the process. The UK and the USA have established official training schemes for manual and real-time monitoring and data handling. The training and certification scheme run by the UK Environment Agency (MCERTS) covers all areas of emission and effluent monitoring, for individuals and organisations. Similarly, the US Source Evaluation Society (SES) has established the voluntary Qualified Source Testing Individual (QSTI) and Qualified Source Testing Observer (QSTO) training and certification scheme. In India, no such systems are in place for real-time emissions monitoring. Up to now, some of the training in real-time monitoring carried out by the CPCB, SPCBs, and other organisations in India has been very basic, non-standardised and non-accredited, and insufficient.

ICSC, under the US Department of State project mentioned earlier, is in the process of planning regional training programmes to support CEMS capacity building in India. Four regional workshops are to be held in India over the next 12-18 months, with provisional dates and locations as follows:

11-15 July 2022 Bhubaneshwar, co-hosted by the Odisha State Pollution Control Board

18-22 July 2022 Bhopal, co-hosted by the Madhya Pradesh State Pollution Control Board

20-24 February 2023 New Delhi (TBC)

27 Feb- 2 March 2023 Visakhapatnam (TBC)

The upcoming training sessions will bring together experts from across India, the USA and Europe to impart knowledge about pollution control technologies, plant operation optimisation and CEMS implementation. The project aims to enable the Indian regulators, policymakers, and operators to deal with one of the critical environmental problems facing India – air pollution, especially from coal combustion in power plants and other industrial sources – through improving performance, helping to meet tighter environmental norms, improving environmental compliance, and providing a framework for effective decision and policymaking.

As far as coal plant compliance with new emission limits is concerned, the ICSC assessment finds that the delay experienced so far is avoidable since the pollution control technologies required are readily available. Compliance could help to achieve a more than 80% reduction in SO2, NOx and PM emissions by 2030. But stakeholders must be empowered with the necessary knowledge and skills and the Indian government must have the courage to take firm and appropriate action that will, within the next decade, result in improved environmental status, health benefits for the population, and demonstrably sustainable economic ambitions.

This article first appeared in Modern Power Systems magazine.