Global coal producers are planning a wave of new capacity additions this decade, with as many as 432 new mining projects currently proposed for development.

More than 2.2 billion tonnes of additional annual coal production is being targeted via these projects, which would deliver a 30% supply increase by 2030 compared to current levels – overshooting the consumption needs of a Paris-aligned energy system four times over.

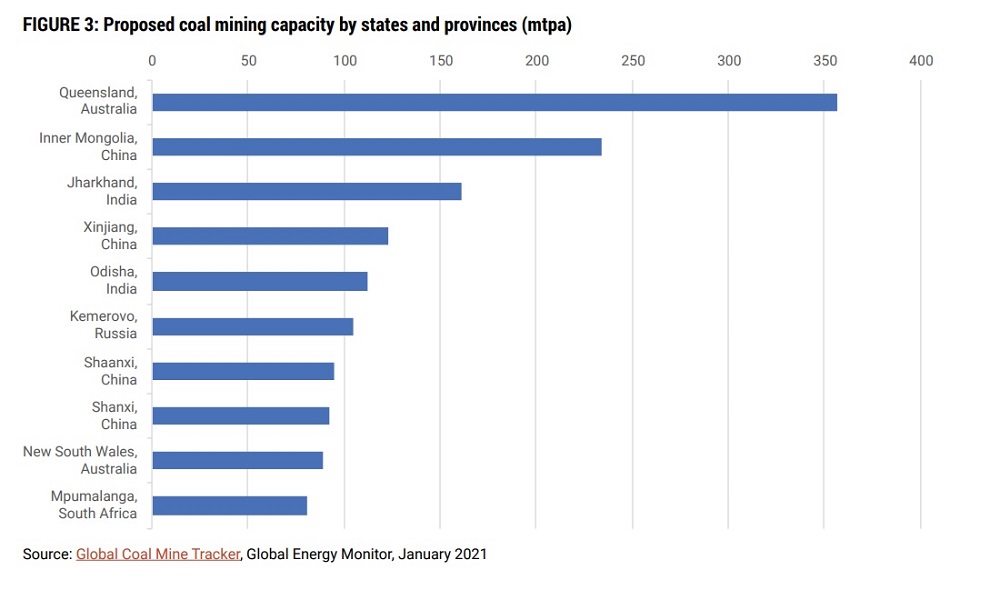

The analysis from Global Energy Monitor (GEM), an NGO that tracks fossil fuel developments around the world, found a handful of regions in China, Russia, India, and Australia account for more than three-quarters of these proposed operations.

The trend is at odds with a UN recommendation that the world’s coal production needs to decline by 11% each year this decade in order to set it on a pathway consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5C by mid-century.

External pressure to abandon coal is mounting, with the International Energy Agency (IEA) the latest to add to the calls to accelerate the fuel’s phase out by urging an end to approvals for new coal supply ventures.

New coal mining projects pose $91bn stranded asset risk

While the analysis raises concern over the prospect of additional carbon emissions, the flip side is that these mines risk becoming stranded assets to the tune of $91bn if governments enact tighter emissions policies and progress towards a cleaner energy system accelerates.

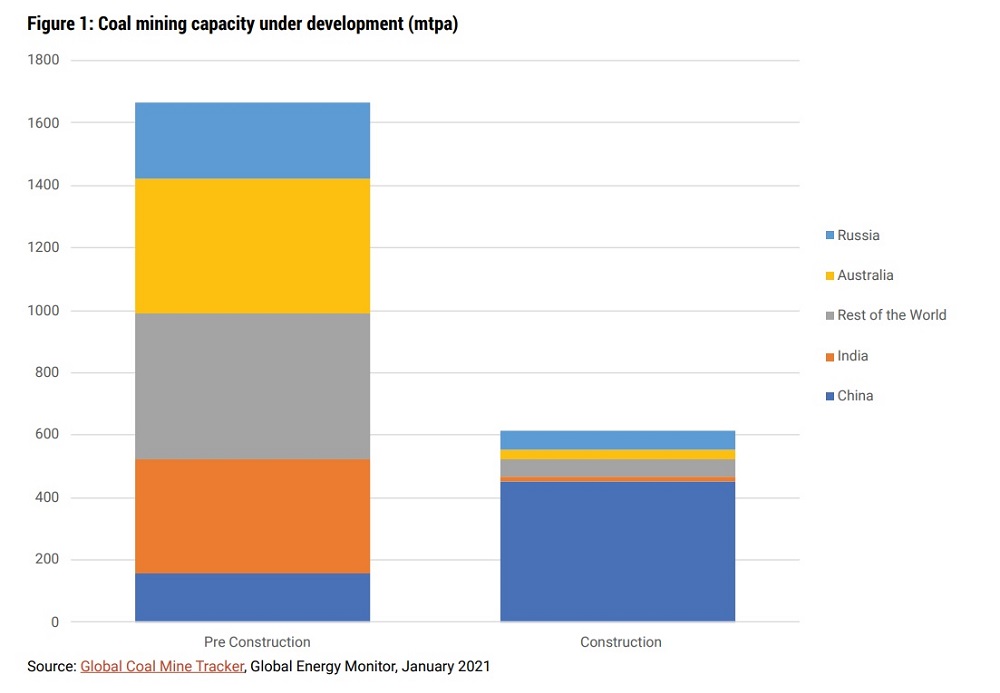

Most of the projects are in the early stages of planning, and therefore vulnerable to cancellation, but a quarter – representing 600 million tonnes of annual coal production – are already under construction.

Almost 25% of the operations are based in four Chinese provinces – Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Shaanxi and Shanxi. In Australia, Queensland has more coal capacity in development – 357 million tonnes annually – than any other region in the world, bolstered by projects in the Bowen and Galilee Basins.

“While the IEA has just called for a giant leap toward net-zero emissions, coal producers’ plans to expand capacity 30% by 2030 would be a leap backward,” said GEM research analyst and report author Ryan Driskell Tate.

“Demand for coal is plummeting and financing for new coal projects is drying up. New mines and expansions of existing mines will be producing coal for a world in which coal is unviable economically, and untenable for the environment.”

Asia, led by China, is propping up demand for new coal production

Coal’s position in the global energy mix is undoubtedly diminishing, although it remains the number one source of electricity worldwide.

A number of regions – notably China, which GEM says has 452 million tonnes of annual production capacity under construction, and a further 157 million tonnes per year in planning – are pressing ahead with policies to continue using the fuel.

At the recent Leaders Summit on Climate, hosted by the Biden White House, China’s President Xi Jinping hinted the country would begin phasing down its coal-fired power fleet – by far the world’s largest – but not until 2026.

The IEA recently warned energy-related carbon emissions are on track for their largest rise in more than a decade, driven by high coal consumption in Asia.

Christine Shearer, programme director for coal at GEM and co-author of the report, said: “If built, these new coal mine projects would produce emissions equivalent to current emissions from the United States.

“Driving up emissions is the fact that many of these new mines are greenfield proposals that will lock-in more long-term production and unleash new sources of methane emissions.”

Some of the world’s largest mining companies have either turned their backs on coal production, or are in the process of doing so, amid rising pressure from shareholders to implement climate-aligned corporate strategies.

GEM said mid-sized mining operations, primarily undertaken by small and independent firms, are the most common in its findings, with the median size for proposed new projects 3.5 million tonnes a year.

More than 70% of proposed new mine capacity is intended to produce thermal coal, although in the US the greater emphasis is on metallurgical coal.