The coronavirus pandemic has “profoundly changed” the outlook for the US shale oil industry, after several champagne years of rapid growth.

Over the past decade, tight oil production tripled across the Lower 48 region – which refers to US states excluding Alaska and Hawaii – driven by the shale fracking revolution and innovative oilfield technologies that have allowed producers access to new, unconventional shale resources.

The US shale boom propelled the country to become the world’s biggest oil producer, with overall output volumes averaging 12.2 million barrels per day (bpd) in 2019 – tight oil accounted for around 63% of that figure.

Peak growth of US shale oil now ‘firmly behind us’

But the spread of Covid-19 has stalled that development – with global lockdowns severely cutting fuel demand and commodity prices dropping to unsustainable levels.

Finances have been squeezed and operations disrupted, while many wells have been shut in as part of efforts to reduce the global oversupply that has put so much negative pressure on oil prices over the past six months.

As a result, research firm Wood Mackenzie estimates that, after consecutive year-on-year production decline in 2020 and 2021, output across the Lower 48 will be almost two million bpd lower than previously forecast for the next five years, with peak production later in the decade expected to be 600,000 bpd below previous forecasts.

“From 2022, the cuts to our US supply outlook and slowing rate of growth mean a growing reliance on Opec capacity to meet demand through this decade,” says a Wood Mackenzie report, authored by upstream analysts Ann-Louise Hittle and Linda Htein.

“Unlike the oil-price downturn of 2014-2016, there is far less room for the sector to make sweeping improvements in well performance and operational efficiency. Companies that survive the unfolding shakeup will need to rebuild trust with investors. Even if they do, higher prices will not mean unbridled growth, making tight oil a less elastic source of supply.

“Peak production may not be behind us, but we firmly believe that peak growth is.”

Bankruptcies on the rise, capital harder to secure

The impact of coronavirus on the US shale patch is already clear to see. In the year to date, 32 exploration and production (E&P) firms in North America have filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, while a further 25 applications have been made by oilfield services companies, according to data from law firm Haynes & Boone.

With the key US oil benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI) currently trading at below $40 per barrel, and not expected to make gains towards $50 per barrel – a level considered more economically sustainable for the sector – until the end of 2021, more bankruptcies are expected to follow.

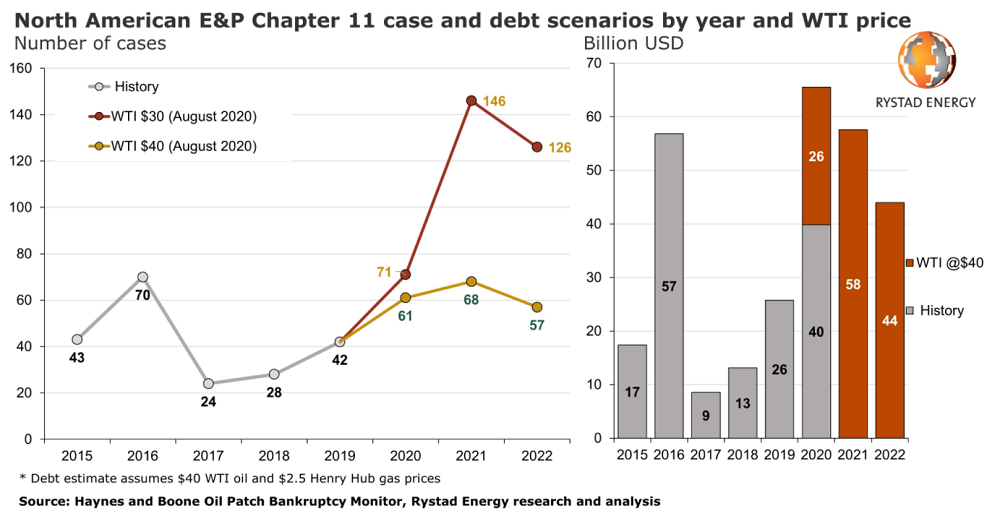

Without a significant upturn, analysis firm Rystad Energy estimates a further 29 Chapter 11 filings across the North American sector before the end of this year – and almost 190 more by the end of 2022, reflecting an estimated debt level of around $168bn.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) recently identified US shale as the hardest to be hit by a decline in capital investment across the energy industry, with spending in the sector expected to halve this year as a result of the pandemic.

As capital proves harder to secure, companies have also been under pressure to reduce production in the face of a huge global oversupply stemming from low demand.

Hittle and Htein say: “In a single quarter of 2020 – Q2 – Lower 48 oil production fell two million bpd (20%), driven largely by shut-ins and curtailments. Drilling and completions activity dropped by more than two-thirds, and these deep cuts will result in at least two consecutive years of decline.

“Investment capital is in short supply with US independents financially stretched, and bankruptcies mounting. Operators can no longer afford to waste capital. Investors won’t allow it and prices don’t offer enough margin to absorb mistakes.

“Exploration of new Permian zones will remain stalled, so those proven commercial today will have to carry the weight of drilling in the near future.

“Inventory exhaustion in core areas and reservoirs is a real problem though. Without risk capital to delineate new reservoirs, there’s little chance of expanding the core. Future wells will be less productive.”

Wave of consolidations likely

The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) says tight oil production has now started to rebound from the difficult second quarter – as well as further disruptions caused by Hurricane Laura last month – as wells are brought back online.

Still, overall domestic oil production this year is expected to be around 800,000 bpd lower than in 2019 at 11.4 million bpd. For 2021, the decline is expected to deepen to 11.1 million bpd – more than one million bpd lower than the 2019 peak.

Wood Mackenzie expects consolidation to become a hallmark of the US shale patch over the coming years. “There are simply too many producers operating at too high a cost,” it explains.

“Deals will be done to shore up cash flow in the near term and ensure resilience in a low-price environment long term. Those that remain will benefit from lower fixed costs, operational efficiencies and economies of scale.

“High-quality, low-cost assets will fall into the hands of capital-efficient operators with strong balance sheets and lower cost of capital.”

Chevron’s recent acquisition of Noble Energy could be a sign of things to come, and Wood Mackenzie says it “would not be surprised” to see two large independents merge within the next six months.

Presidential election adds further uncertainty to US shale oil outlook

The upcoming presidential election in November adds further uncertainty to the outlook for US shale.

President Trump has made “energy dominance” a central focus of his administration, which has reversed several Obama-era regulations placed on the oil and gas industry, including permitting restrictions and controls on methane-emissions standards.

Re-election and four more years under his stewardship might signal an extension of this friendly policy environment, while a win for Democratic rival Joe Biden would likely see a stronger focus on climate issues and clean energy.

“With change comes a new reality that tight oil projects will likely be susceptible to delays, take longer to execute, and cost more,” say Hittle and Htein. “Environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) pressure will be far more consequential for tight oil’s future than it was for its past.”