In early 2019, the US Department of Energy (DOE) announced plans to build a Versatile Test Reactor (VTR) — a fast-neutron research reactor capable of performing irradiation testing at much higher neutron energy fluxes than currently available in the USA. After initial enthusiasm for the project, support has now waned. Congress rejected proposals for funding for FY 2022, leaving the project to look elsewhere for finance based on its geopolitical and strategic importance.

DOE’s Office of Nuclear Energy established the VTR programme in 2018 in response to the Nuclear Energy Innovation Capabilities Act (NEICA). NEICA directs DOE to assess the mission need for and cost of a versatile reactor-based fast-neutron source with high neutron flux, irradiation flexibility, multiple experimental environment capabilities and space for many concurrent users.

In February 2019, VTR cleared Critical Decision 0, demonstrating a mission need requiring investment — the first in a series of project approvals. DOE then announced the start of the VTR Project. Congress supported the VTR with $35 million in 2018 and $65 million in 2019.

In November 2019, Battelle Energy Alliance (BEA), which manages Idaho National Laboratory (INL), announced an Expression of Interest seeking an industry partner to design and construct the VTR. In January 2020, a collaboration between GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy (GEH) and TerraPower supported by Energy Northwest was announced. In August 2020 BEA initiated contract negotiations with a team led by Bechtel National Inc to support the design and build phase. In September 2020 the DOE announced it had approved Critical Decision 1 for the VTR project. This is the second step in the formal review process, during which federal committees reviewed the conceptual design, schedule and cost range, and analysed alternatives. DOE also issued a Notice of Intent to prepare the environmental impact statement (EIS).

At that time Argonne National Laboratory (ANL) welcomed the development. “Argonne’s engineers are also contributing in many areas of the project, including reactor design, experiment design and fuel design,” said Jordi Roglans, ANL VTR deputy project manager. He said Argonne’s history of expertise in sodium-cooled fast reactor technology equips it to play a lead role in the design of the core of the VTR and the safety analysis.

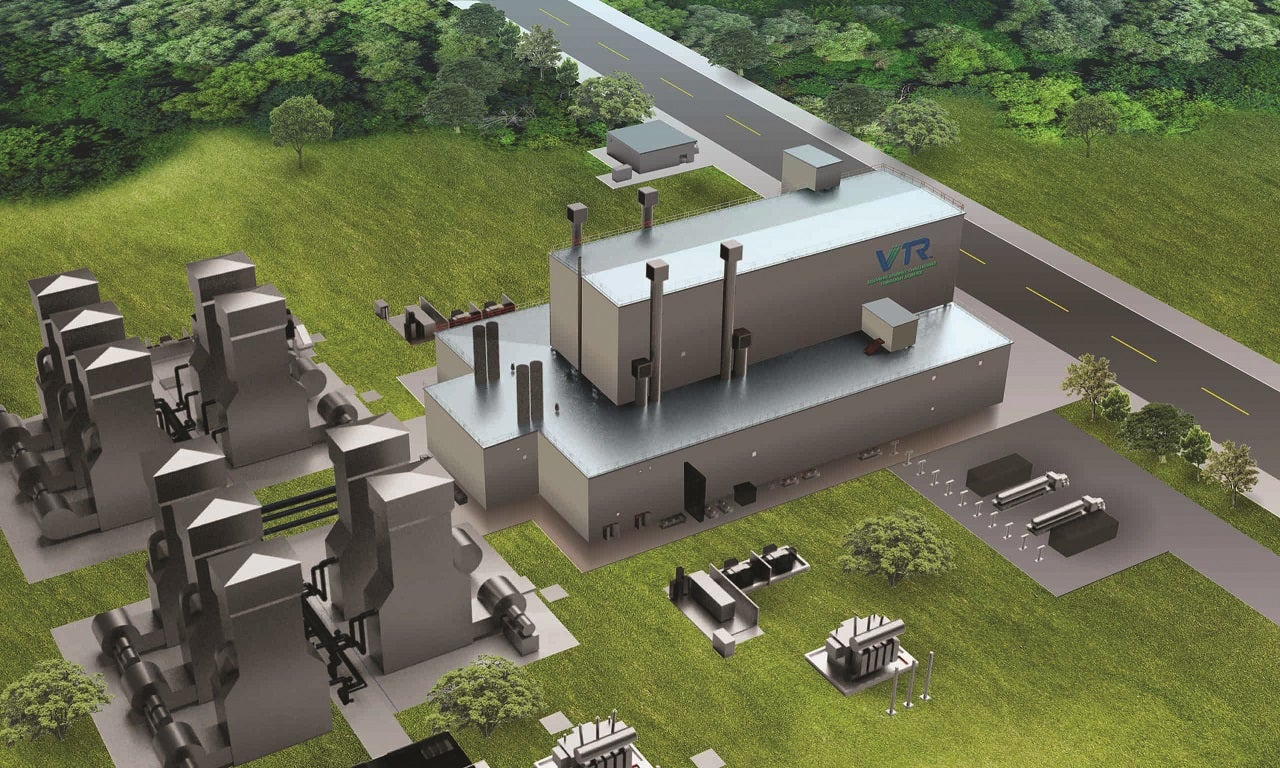

To minimise the project risk, researchers wanted to adapt existing designs for the new reactor. “We wanted to start with technology that had been demonstrated to the fullest extent possible so that we could minimise the development work required for the design and construction of the VTR,” Roglans said. The conceptual design for the VTR is an adaptation of General Electric-Hitachi’s PRISM design, which was initially part of DOE’s Advanced Liquid Metal Reactor programme. The PRISM design has been adapted to the VTR by removing electricity production elements and adapting the core and primary system to facilitate the test mission.

Roglans said building a reactor like the VTR was a challenge. “The Department of Energy has not built a new test reactor in many years and establishing the supply chain for the unique components of the VTR will be demanding, so efforts to ensure that we have the supply chain we need have started early.” However, he added that, “The addition of the VTR to the US nuclear research infrastructure will support leadership in nuclear energy research, safety and security, while also supporting US industry partners as they commercialise new technologies.”

Timeline for engineering design

The VTR project was expected to move to the engineering design phase as soon as Congress appropriated funding. In December 2020 the DOE invited the public to review and comment on a Draft EIS for the sodium-cooled fast-neutron-spectrum test reactor. The draft, prepared in accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), analyses potential impacts of the VTR alternatives and options for reactor fuel production on various environmental and community resources. The EIS evaluated:

-Construction and operation of the VTR at INL or the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL). This includes operating and performing experiments in the VTR, post-irradiation examination of irradiated test specimens in hot cell facilities, and used fuel conditioning and storage pending shipment for interim or permanent disposal.

-Production of fuel for the VTR at INL and/or the Savannah River Site including preparing feedstock for the fuel, fabricating fuel pins, and assembling the fuel pins into reactor fuel.

-A no-action alternative under which DOE would not pursue the construction and operation of a VTR.

The Draft EIS identified construction and operation of at the INL Site as DOE’s preferred alternative. Existing facilities (modified as necessary) would be used for the VTR support facilities. The public was encouraged to comment on the draft EIS and DOE also held two public hearings. According to DOE, the VTR could be completed as early as 2026 and it said in September 2020 that it will make a final decision on the design, technology selection and location for VTR following the completion of the EIS and Record of Decision, which is expected in late 2021.

Funding difficulties

However, this timetable is increasingly unlikely in view of continuing Congressional lack of enthusiasm for the project. DOE had requested $295 million for FY 2021 for the project, but things did not go according to plan. Congress instead reduced funding from $65 million to $45 million after senators expressed concern about its cost, which DOE had estimated at between $2.6 billion and $5.8 billion. Congress also directed DOE to reformulate the project as a private-public partnership.

The situation was further complicated by the fact that DOE is also pursuing other research reactor projects as part of its Advanced Reactor Demonstration Programme (ARDP), which is clearly taking priority.

In the FY 2020 budget, DOE had received $230 million to start a new demonstration programme for advanced reactors. ARDP elements include Advanced Reactor Demonstration, Risk Reduction for Future Demonstrations, Regulatory Development, and Advanced Reactor Safeguards. Through cost-shared partnerships with industry, ARDP will provide $160 million for initial funding to build two reactors that can be operational within the next 5-7 years.

In 2021, DOE awarded cost-sharing agreements to TerraPower and X-energy to demonstrate two advanced reactor designs, saying it expects to spend $3.2 billion on the projects over seven years pending funding availability. Terrapower’s project is a 345MWe sodium-cooled fast reactor with a molten salt-based energy storage system and Congress made clear its reluctance to fund two apparently similar projects.

The Biden administration’s fiscal year 2022 budget request for DOE proposes to increase funding for the Office of Nuclear Energy by 23% to $1.85 billion. However, the House and Senate are only proposing increases to $1.68 billion and $1.59 billion, respectively. Within that, the administration proposes increasing funding for the ARDP from $250 million to $370 million and DOE is requesting $246 million to continue early work on the projects in the coming fiscal year. The request also proposes to increase funding for the National Reactor Innovation Center from

$30 million to $55 million, in part to support the development of reactor testbeds.

The request also included $145 million to continue early work on the VTR but it said that the administration now plans to sequence the reactor’s design and construction to follow TerraPower’s demonstration project — it recently announced plans to build the reactor at a retiring coal plant in Wyoming. That will take advantage of knowledge gained from developing its similar design and optimise the use of resources and expert personnel across the two projects.

The Senate proposes to meet the administration’s request to increase funding for ARDP from $250 million to $370 million, according to the American Physics Institute. The House proposes $395 million, with the additional funding allocated to efforts to reduce technical risk on potential future demonstration projects. In addition to full demonstration projects being pursued with the companies X-energy and TerraPower, the programme is supporting five risk-reduction efforts and three concept-development projects. But for the VTR, the House and Senate reduced funding for the proposed user facility to zero, offering no reason or any indication of whether the project could continue using funds already appropriated.

Why a need for demonstration and test reactors?

DOE is continuing to argue that both demonstration reactors and the VTR are needed. In an article published by the Office of Nuclear Energy in July, Kathryn Huff, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary for Nuclear Energy said: “Both demonstration and test reactors are necessary to support the development and commercial deployment of the new reactor technologies that will expand access to reliable, clean energy.”

She said many US vendors are planning to demonstrate their reactors within the decade, “but in order to innovate faster and improve upon these designs over time, we also need the necessary infrastructure to support their development and, more importantly, their commercial deployment”. She argues that a fast neutron test source would set up the US for success in a future clean energy market estimated to be worth billions. “Without VTR, US innovation will fall behind other countries which have fast neutron test reactors, and we simply can’t let that happen.”

On its FAQ page DOE explains why the VTR cannot be combined with the ARDP reactor. “While the test and demonstration reactors both use sodium-cooled fast reactor technology, their principal missions, and therefore their detailed designs, are very different. Each of them has a unique reactor core and operating cycles tailored to their specific mission.”

The ARDP mission is to license and operate advanced fission systems that are affordable and ARDP demonstration reactors will use long-lasting fuel for operating cycles generally exceeding one year or more. But the VTR uses high-performance fuel with 100-day operating cycles, followed by a 20-day outage to refuel and replace experiments and it is “designed to meet a testing mission of providing an advanced fission environment — specifically, a high flux neutron environment — to support accelerated fuels and materials experiments.” DOE says that while ARDP uses fuel geared toward a marathon, VTR uses fuel geared toward a 100-metre dash. “Trying to combine these two different missions will result in a reactor that is not efficient at either producing power or providing an advanced irradiation testing environment.”

Currently, there are very few capabilities available for testing fast neutron reactor technology in the world and none in the USA. Russia has the ageing BOR-60, which is widely used by researchers worldwide. It is already constructing its replacement — the MBIR reactor, intended to be the centre of an international research facility.

In its description of the VTR, DOE notes: “The United States has long been a leader in the development of nuclear technologies. However, as there is currently no fast neutron testing capability in the US to support advanced reactor research and development, US industry has gone overseas for this capability.” The VTR “is intended to fill this long-standing gap.”

Concerns were voiced in an article in August by the Center for the National Interest, The Versatile Test Reactor is Crucial for US Global Leadership in Nuclear Energy. The authors, Thomas Graham, Jr and Richard W Mies, each retired admirals and nuclear specialists, say: “If the United States gives up the chance to build the VTR, then it could be another step to relinquishing the mantle of global leadership in advanced nuclear technologies and likely ceding that mantle to Russia …

“Allowing the only fast neutron test facility in the world to reside in Russia — without building a similar capability in the United States — could also enable the Russian nuclear energy sector to leapfrog over the US nuclear energy industry.”

A post in the Atlantic Council blog suggests that funding opportunities may still exist. It says excluding funding “is a grave error that will have far-reaching ramifications for US nuclear energy leadership”. However, it notes that there are “upcoming legislative opportunities to rectify this error”.

The article says the estimated cost of the VTR “pales in comparison to the DOE’s annual budget” and that “expert predictions of the annual cost of climate change … further dwarf the estimated cost of the VTR”, while “opportunities exist to defray the VTR’s costs, most notably through international cooperation and funding from civil nuclear allies who wish to test their own nuclear fuel and materials”.

The Atlantic Council notes that “Congress still has opportunities to support the VTR, especially through the reconciliation process and — looking ahead — through Fiscal Year 2022 spending. As part of reconciliation, the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology has proposed $95 million for the VTR.”

It concludes: “Each of the three requisites of US nuclear innovation — the demonstration of new reactors, support for new fuels, and a domestic testing capacity — plays a different role in the nuclear ecosystem. All three support the development of the next generation of nuclear energy technologies.”

DOE has said that if the final design and construction begin in 2023, VTR will be fully operational by the end of 2026, pending funding appropriations by Congress. The key word here is “pending”, given Congress’s lack of enthusiasm for the project. As Congressman Randy Weber (TX) lamented on the House Floor during the discussions: “The 2022 appropriations bill provides no funds, zero, zip, zilch, nada, to keep the Versatile Test Reactor project on budget and on schedule.” It remains to be seen whether alternative sources of funding can be found.

This article first appeared in Nuclear Engineering International magazine.