It’s one of the most contentious issues among environmental campaigners and isn’t going away anytime soon – but what is fracking?

The complex engineering process for extracting shale gas is long established in countries such as the United States but has been banned or paused in many countries including the UK, Ireland, France, Germany and the Netherlands.

UK firm Cuadrilla was granted permission in 2018 to begin fracking at a site in Preston New Road, within the parish of Westby-with-Plumptons, after a last-ditch attempt to stop it was turned down.

However, following several small earthquakes near the Lancashire site, the government halted all fracking in England in late 2019, and warned the shale gas industry that it would not support any future projects.

This decision was taken after a study revealed it was not possible to exclude “unnacceptable” consequences for residents living close to fracking sites.

The Oil and Gas Authority report also claimed it was not possible to predict the magnitude of earthquakes that the process might trigger in future.

At the time, the government said it would not support any further fracking projects “until compelling new evidence is provided” to confirm the process is safe.

The Preston New Road site – the UK’s only fracking facility – has been closed ever since with no immediate prospect of extraction being restarted on the site.

Fracking supporters say it will create a new industry that brings investment, jobs and energy assets to the UK, but environmentalists heavily oppose it due to concerns it could contaminate the water supply, cause earthquakes and destroy natural landscapes.

For the wider public, though, the unconventional drilling method being pursued in England is a complex engineering process that many don’t fully understand.

Here, we break down what fracking involves.

What is fracking? Explaining hydraulic fracturing

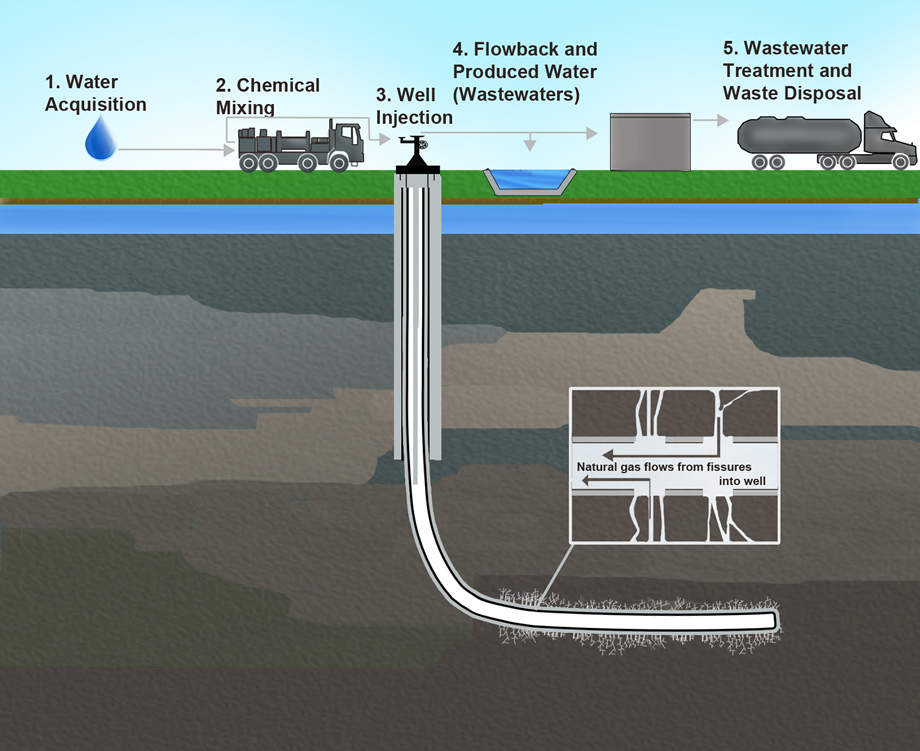

Fracking is a type of drilling technique that involves fracturing rock deep underground in order to extract shale gas – a natural fuel that is trapped within shale formations.

Energy firms will drill vertically down into the ground at between 6,000ft and 10,000ft, and then horizontally by more than a mile.

Hairline cracks with a radius of about 300ft are then opened up in the rock by pumping in water, sand and some chemicals, allowing gas to flow into the pipes.

Permission is needed to begin shale gas extraction

Oil and gas companies that hope to explore for shale gas must first obtain a Petroleum Exploration and Development Licence (PEDL) from the government’s Oil and Gas Authority.

This allows a company to pursue a range of oil and gas exploration activities, subject to necessary drilling and development consents, and planning permission from the local authority.

Once a company has negotiated the lease of land on which it wishes to frack, it must seek planning permission for pre-fracking research.

This includes seismic surveys, which provide 3D images of the underground resources, and a vertical drilling to obtain examples of the rock.

Should the firm decide there are sufficient shale gas reserves, it must seek further planning permission.

The three stages of shale gas extraction

There are three stages to fracking, with the final phase lasting decades.

Drilling contractors will typically create up to 30 wells over a five-week period, using a 180ft sub-structure similar in appearance to those used on offshore oil rigs.

A fracking team will then take over the site for about two weeks to open up the fissures in the rock and collect the shale gas through pipes.

Once this work has been completed, a production unit will create a small well pad of pumps feeding into green containers to extract the gas over many years.

The containers are connected to the national grid supply system for the lifespan of the well.

The dangers of fracking

Opponents believe fracking carries a significant risk of contamination with hazardous chemicals, not least the water supply – where there have been numerous complaints of tap water being discoloured, causing illnesses and even flammable in the US.

There are those who argue it contributes to global climate change and destabilises underground rock formations to induce earthquakes.

They also question the economic sustainability of fracking, saying it would require thousands of wells that would transform the countryside, where natural landscapes would be destroyed and organic farmers would be under threat.

Benefits of shale gas

Fracking companies contend that water supplies should not be affected because the piping structure should protect gas from leaking into the aquifer, the underground layer of rock from which groundwater can be extracted using a water well.

Pipes have up to seven layers, each reinforced by concrete, as they pass through the aquifer and are reduced to one layer of steel at about 3km deep.

Supporters also claim that fracking has helped to revolutionise the energy industry in the USA and that the UK could become a net exporter of gas, rather than spending money exporting from other countries.

They also believe the industry could create tens of thousands of jobs and attract billions in investment in communities that were once dependent on mining.

The UK government’s position

After initially supporting the fracking industry – believing the gas had the potential to provide the UK with greater energy security, economic growth and jobs – the UK government reversed its stance on the basis of new scientific analysis received in 2019.

Minister took the decision to withdraw support and halt all fracking in light of a report from the by the Oil and Gas Authority (OGA) which found that it is not currently possible to accurately predict the probability or magnitude of earthquakes linked to fracking operations.

The government confirmed in November 2019 that the process was being paused across the UK “unless and until further evidence is provided that it can be carried out safely here”.

Business and Energy Secretary Andrea Leadsom said at the time: “Whilst acknowledging the huge potential of UK shale gas to provide a bridge to a zero carbon future, I’ve also always been clear that shale gas exploration must be carried out safely.

“In the UK, we have been led by the best available scientific evidence, and closely regulated by the Oil and Gas Authority, one of the best regulators in the world.

“After reviewing the OGA’s report into recent seismic activity at Preston New Road, it is clear that we cannot rule out future unacceptable impacts on the local community.

“For this reason, I have concluded that we should put a moratorium on fracking in England with immediate effect.”