In the UK, floating wind is proving its potential to be a reliable source of renewable energy, says the operator of Hywind Scotland – the world’s first floating offshore wind farm.

Norway’s Equinor said its 30-megawatt (MW) project, located roughly 30km off the eastern Scottish coast near Peterhead, has for the third year running achieved the highest average capacity factor of any UK wind farm.

This ratio of actual energy output versus maximum possible output has averaged 57.1% at Hywind Scotland in the past 12 months, which compares to around 40% for other offshore wind projects around the country.

It is a notable achievement, given the UK has one of the world’s largest offshore wind fleets.

Equinor says a higher capacity factor means lower intermittency and higher value, and that the presence of Hywind at the top of this table shows the project has “truly proven the potential for floating offshore wind”.

Floating offshore wind can be deployed in deep waters, opening up new regions to potential deployment

While the industry for “fixed” wind farms, both onshore and offshore, has developed significantly over the recent years and is now among the most mature of renewable energy technologies, floating offshore ventures have been slower to gain traction.

Floating wind offers a geographical flexibility unavailable to fixed-bottom offshore turbines, however, able to be deployed in a wider range of locations – notably in deep waters where wind speeds are often much higher and more consistent than coastal areas.

Hywind Scotland was the world’s first commercial floating project, installed in 2017, and in the years since has provided valuable operational data and results that will inform the wider industry and help drive future development.

“The turbines are covered in sensors, to extract as much data from the wind farm as possible,” said Sonja Chirico Indrebø, plant manager for Hywind Scotland. “We’re monitoring everything from ballast, mooring, structural strains and the more regular wind turbine sensor data, looking at how best to optimise this innovative technology as we prepare to develop at scale.

“We’re sharing parts of this data across industry to help the advancement of the technology globally and more widely than just our own operations.”

In the UK, where offshore wind has become the dominant renewable technology of the country’s push to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, the government has recently announced plans to develop 1 GW of floating wind capacity by the end of this decade.

Equinor says the success of Hywind Scotland shows this target could be upgraded – “reaching up to 2 GW by 2030 and building a multi-GW pipeline of projects to deliver the UK’s longer-term net zero objectives”.

“We believe Scotland has the potential to build a globally-competitive offshore wind industry, including a real chance to enhance the development of floating offshore wind,” said Sebastian Bringsværd, head of floating wind development at Equinor.

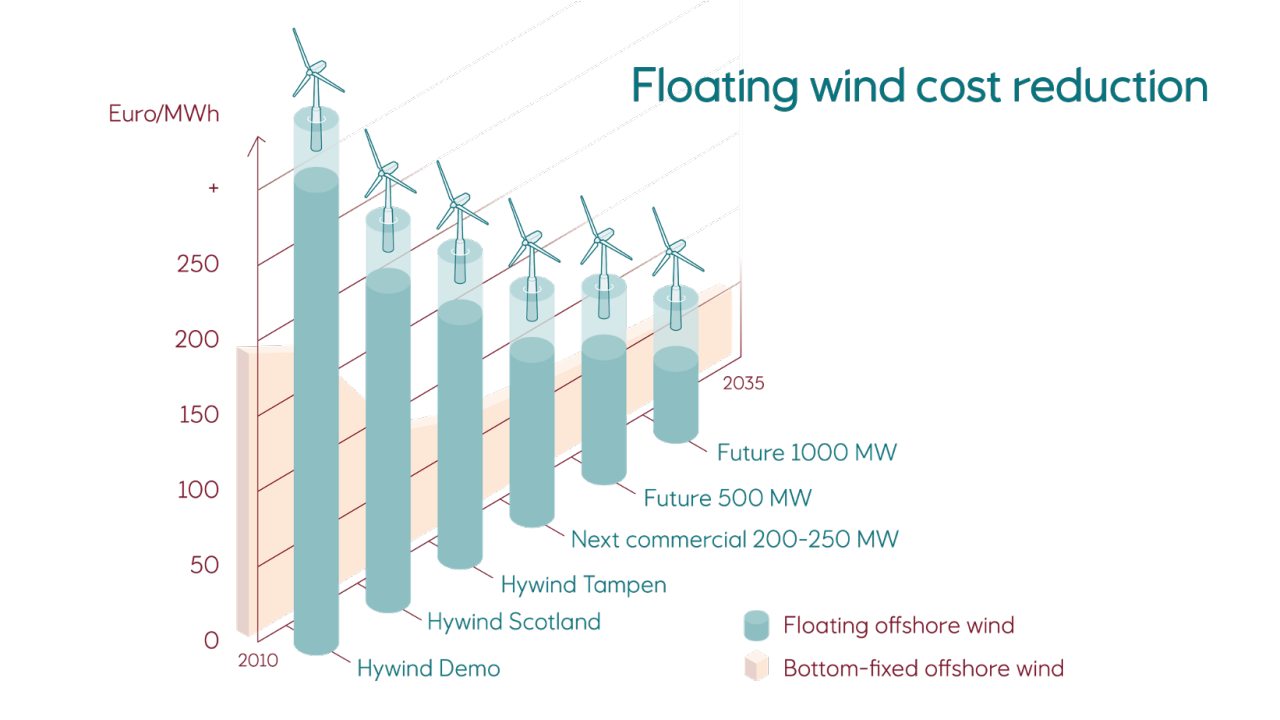

Cost reductions achieved through scale

Elsewhere, the Norwegian energy major is currently building its Hywind Tampen site in Norway’s North Sea.

Expected to come online in 2022, the 88MW project will become the world’s largest floating offshore wind farm and mean the company operates one third of the world’s floating wind production capacity.

Analysts have also identified Asia as a likely region for future growth in floating offshore wind, particularly regions like Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, although widespread adoption remains dependent on the costs of the technology coming down.

With scale being key to lowering costs, Equinor says it has already seen a capex reduction per MW of 70% from its initial demonstration project to Hywind Scotland – and expects a further 40% reduction with the commissioning of Hywind Tampen.

“The global energy industry has been pleasantly surprised by the rapid decline in the cost to deploy fixed bottom offshore wind,” Bringsværd said.

“We’ve been working on floating offshore wind for more than ten years and we see that significant cost reductions can be achieved through scale and experience, paving the way for floating to become fully commercialised.”