As well as protecting itself from Covid-19, the mining industry in Australia has also used the pandemic to make more sweeping operational changes. World Mining Frontiers writer Andrea Valentino chats to Debbie Smith, a managing partner at PwC Australia, and Tania Constable, CEO of the Mining Council of Australia, about the lessons learned in shielding the nation’s mining industry.

Mining has been fundamental to Australia’s culture and economy for nearly two centuries. Lead was first mined back in 1842 in what is now the dusty Adelaide suburb of Glen Osmond, and by the end of the decade was earning more than wool or wheat for the colony.

Gold was discovered in the desert interior shortly afterwards, with frontier towns with names like Bendigo and Ballarat and Big Bell exploding as extravagantly as the leaves on a bright pink waratah plant.

As early as the 1850s, in fact, Australia was producing almost 40% of the world’s precious yellow metal.

The national fever dream produced by the gold rush of that decade has long since passed. The cultural impact of those days, however, has not. Stories about Aussie miners and their adventures continue to line bookshelves and television listings.

One recent film, exploring the friendship between a sheepdog and a gang of local miners, was lauded as one of the most “widely appealing” Australian movies in years, with the eponymous Red Dog ultimately being memorialised in a touching statue.

Unfrayed, too, is the industry at large. According to research by Statista, mining in all its shades employs more than 130,000 Australians, accounts for 6.4% of the country’s economic output, and contributes a stonking 60% of its exports. No wonder, then, that governments both local and federal have worked so hard to support it.

In Western Australia, for example, the parliament in Perth has invested heavily in promoting brine extraction, crucial for securing special minerals like potash. In the Northern Territory, officials helped establish the first mine owned by the local Aboriginal community. All this is shadowed at the national level, with the government subsidising mining to the tune of A$4bn ($2.9bn) each year.

Then came Covid-19. An airborne virus that spreads rapidly in enclosed spaces, the disease threatened to shut down Australia’s pits, just as it did elsewhere. In South Africa, for instance, the government ordered practically all of the country’s 450,000 miners to lay down their picks. And after several Covid-19 deaths in Chile, Codelco, the world’s largest copper producer, shuttered its Chuquicamata facility in the north of the country.

Given the vital importance of mining to the Australian economy, it goes without saying that anything similar happening down under would have had catastrophic consequences.

And yet, Australia’s mines not only kept on running, but they also managed to do so with a remarkably low-rate of infection. That the sector suffered so much less than its international rivals was a product of careful planning and a recognition among policymakers that the country simply couldn’t afford to make a mistake when it came to protecting one of its leading export industries.

“We didn’t rush to unnecessarily shut down businesses that were keeping people employed and the economy going,” says Debbie Smith, a managing partner at PwC Australia in Brisbane.

Instead, the Australian government and national mining operators hunkered down, spotting an opportunity in this global health crisis to clean up shop, adopt new technology and hone remote-working practices so that the sector – in theory – could emerge stronger than ever.

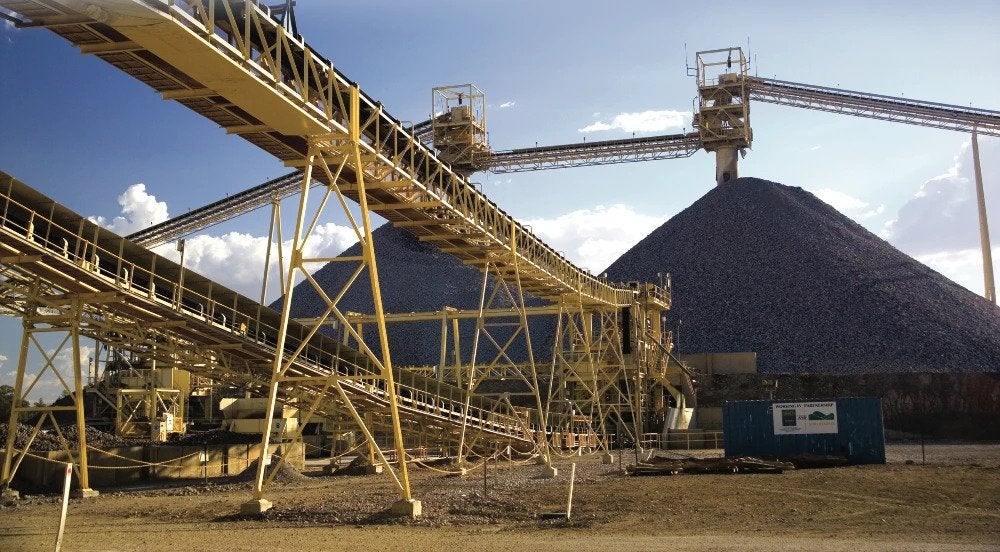

Despite Covid-19, mining in Australia remained open for business

At first, measures to protect the mining sector in Australia amid Covid-19 were led by the federal government, which declared the country’s constellation of pits an essential industry, a decision backed by its regional counterparts. As such, practically all the mines between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific stayed open.

And while production of some minerals certainty did decline in the initial panic – Newcrest Mining announced that gold yields had dropped by almost 17% by the end of March 2020 – keeping mines running is credited by experts as literally having saved the Australian economy.

“The industry is acutely aware of its responsibility to sustain jobs,” explains Tania Constable, CEO of the Mining Council of Australia (MCA). “There has been unanimous support for a coordinated national approach, ensuring continued operation of the resources sector as an essential industry by the nation’s resources ministers.”

As Constable hints, Australian mining’s continued buoyancy was secured by the country’s politicians – who did far more than just putting mining in the same bracket as pharmacies and grocery stores.

Between extending debt relief, supporting the online arbitration of disputes and loosening travel restrictions, helping miners cross state boundaries, it seems fair to conclude, with Constable, that the sector received “broad support” from leaders in town halls and parliaments up and down the country.

Beyond specific government action, though, mining in Australia was able to weather the Covid-19 pandemic’s shock because of ingrained safety protocols. Like their counterparts the world over, Constable says that health and safety has always been the “number one priority” for Australian mining companies, which, in turn, has helped the industry adapt quickly.

This is unsurprising. In such a dangerous industry – six miners recently died over 12 months in Queensland alone – staff have to be ready for anything. To put it another way, Covid-19 may have been unexpected, but protocols like stocking extra equipment and immediately quarantining sick workers still proved useful.

The geographic spread of Australian mining helped too. With 85% of the population living in urban areas, and most mines spread across a continent of scrubland and desert 32-times larger than the UK, it’s proved relatively simple to keep industry workers away from both Covid-19 and their fellow Aussies.

“Australia is a very big country that is far less densely populated than many others,” says Smith. That reduced the risk of “hotspots” of community transmission.

To take just one example, consider Newmont’s Tanami gold mine. Located in the wilderness of the Northern Territory, the nearest settlement is the remote Aboriginal community of Yuendumu, some 270km away.

Taking the opportunity to reform

It would be wrong, though, to imply that government backing and isolation in the bush meant mining in Australia could just settle back to its old ways once the surprise of Covid-19 had passed.

On the contrary – and to its credit – the industry has used the virus as the launching pad for a number of broader reforms. That begins, suggests Smith, with remote work.

Even before this year’s crisis, Australia’s colossal size made sending staff off to distant mining outposts unappealing – not least to workers themselves. Why would workers want to spend a fortnight in Yuendumu if they’d grown used to Melbourne coffee shops? And now, of course, with the added risks of contracting a deadly illness, everyone has become even more alert.

No wonder, then, that Australian mineral companies are working hard to keep staff remote. At Interlate, a remote mining company in Brisbane, for example, bosses report a “stronger pull” for new digital services.

At Fortescue’s Integrated Operations Centre, meanwhile, white-collar staff in Perth can now operate a mine, rail and port network about as far away as London is from Venice.

And for staff who absolutely have to be out in the middle of nowhere? Like mining companies elsewhere, Australian businesses are moving away from the so-called “fly-in-fly-out” approach, instead asking workers to stay in the field for several weeks.

Apart from giving them time to quarantine, this protects vulnerable Aboriginal communities from the risk of infection – no small thing when you remember that they’re 6% more likely to suffer from respiratory illnesses than their non-Aboriginal counterparts.

At the same time, the industry is experimenting with that frequent partner of remote work: automation.

“For years,” explains Constable, “the Australian mining industry has been a global leader in the development and deployment of new technology and techniques, including data analytics, automation, robotics and AI. This leadership will continue in the post-pandemic era.”

A fair point, particularly if you look at industry press releases. Back at Perth’s Integrated Operations Centre, for example, Fortescue recently committed to making all the vehicles at its Pilbara mine fully autonomous. In the same region, Rio Tinto has agreed to buy a fleet of 20 autonomous Caterpillar tracks for its new Koodaideri operation.

All this is a piece of what Smith calls the “acceleration” of change in an age of social distancing, an argument she extends to supply chains too.

In a world where airports can be closed at a moment’s notice, mining companies must move towards more local arrangements. That’s especially true in Australia, where state and provincial governments can close frontiers to their fellow Australians, and where it takes nearly two days of solid driving to get from Sydney to Perth.

Fortunately, it seems that here, too, the industry is taking stock – both for its own sake and to protect the economy at large. Companies are tweaking their accounts to pay suppliers on time, Smith says, and hunting about for local partners.

Once again, Aboriginal Australians are a major focus here, with BHP promising A$100m ($73.3m) to help “small, local and indigenous” suppliers.

The future of extraction

All these developments will, of course, help mining in Australia both now and later, whenever the Covid-19 pandemic subsides and people get on with their lives. Yet, at a more basic level, stakeholders in the industry and government are already looking ahead.

A prime example is the MCA’s roadmap for post-pandemic recovery. Apart from investing in more technology and reconfiguring how miners work, it proposes a raft of other measures too.

Among other things, Constable highlights a more competitive tax system and revamped exploration licensing. “Australia cannot take its global leadership in mining and minerals processing for granted,” she says. “Overseas competition will continue to intensify and government action on these policies is necessary to support the mining industry.”

These fears are understandable. China, after all, now produces about half the world’s steel and imports more than 70% of its seaborne iron ore. Its growing political power causes challenges too, with rumours that the People’s Republic was on the verge of banning Australian coal imports.

Faced with all this, can Australia, for all its space, a country of just 25 million, really compete? Challenging too – in the nearer term anyway – is the resurgence of Covid-19, with new spikes over the summer of 2020 showing how volatile the illness can be.

All the same, if one looks at how much the industry has done already, there’s little reason to doubt Australian mining’s viability. From Bendigo and Ballarat, back in the frontier days of the 19th century, remote work and automation now beckon – even if dogs are probably kept well away from the mines that dot the outback today.

This article first appeared in World Mining Frontiers magazine.