Whether it’s Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg leading school strikes or Donald Trump pulling the US out of the Paris Agreement, the climate change discussion almost universally takes place in the western world. But many believe it’s Asia where many of the biggest emissions problems need to be solved in a global effort. Dan Robinson reports from last month’s International Petroleum Week conference in London, where the East was placed firmly under the spotlight.

Its future direction could “make or break the Paris climate goals”, according to a recent report, while it was on the receiving end of a lecture by a US think-tank’s senior fellow for “lagging behind in preparing for the deluge”.

Asia is, as one industry expert puts it, the “800-pound gorilla in the room” when it comes to climate change.

Whenever the global warming debate comes up, which is becoming more frequent by the day, there will often be at least one dissenting voice who wants to point out the region isn’t contributing to cutting emissions like countries in the West.

It’s an easy stick to beat the region with, given that China and India in particular are reversing a global trend of removing coal from the energy mix by opening new plants embracing the “dirtiest” fuel of the lot.

Statistics behind climate change and energy consumption in Asia

While the rest of the world reduced its coal capacity by eight gigawatts (8GW) in the 18 months to June 2019, China increased its stock by 42.9GW, according to the NGO Global Energy Monitor – which predicts the gulf between the Asian superpower and other countries will only widen.

Meanwhile, coal-powered electricity has risen in India from 68% in 1992 to 75% in 2015.

The neighbouring South-east Asia is one of the few regions where the share of coal in the power mix increased in the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) most recent figures for 2018 as new plants continue to come online.

Data is stacking up to highlight the region’s carbon problems, with the BP Statistical Review of World Energy showing Asia-Pacific’s 43.2% share of 2018 energy consumption is more than North America (20.4%), Europe (14.8%), and Central and South America (5.1%) combined.

China alone accounted for 23.6%, with the next largest consumer being the US at 16.6% and India taking a distant third place with 5.8%.

And it’s the same order when it comes to carbon emissions, as China leads with 10.8 billon tonnes of CO2 in 2017 – 29% of the world’s total, despite its 1.4 billion population being 18% of the global headcount – followed by the US with 5.1 billion tonnes (14%) and India with 2.5 billion tonnes (7%).

The European Union’s 27 member states together contributed 3.5 billion tonnes, or one-tenth of the global total.

Such stark differences have created a narrative that China has an “addiction” to fossil fuels, in particular coal, and wider Asia needs to bear the brunt of the so-called energy transition if climate change is to be halted.

But more tactful observers want to see the 36 members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) – which exhausted 40.9% of the world’s energy despite only accounting for about one-fifth of the total population – take more responsibility to help the East in finding answers to the global warming problem.

Addressing a room of oil and gas executives at the IP Week conference in London, Peter Godfrey speaks about how “the problem is global but the solutions are regional”.

The managing director of UK-based the Energy Institute professional body’s Asia-Pacific division, who is located in Singapore, adds: “Objectives are very different – the energy transition isn’t just a one-way street.

“Different countries have different purposes and it’s very important to recognise that.

“We all know that throughout history, at the heart of civilisation has been energy and wealth creation, but it’s coming at a cost of climate change.

“It’s very important to recognise Asia is the 800-pound gorilla in the room when it comes to energy because its continued economic growth and rising standards of living are almost entirely dependent on energy.

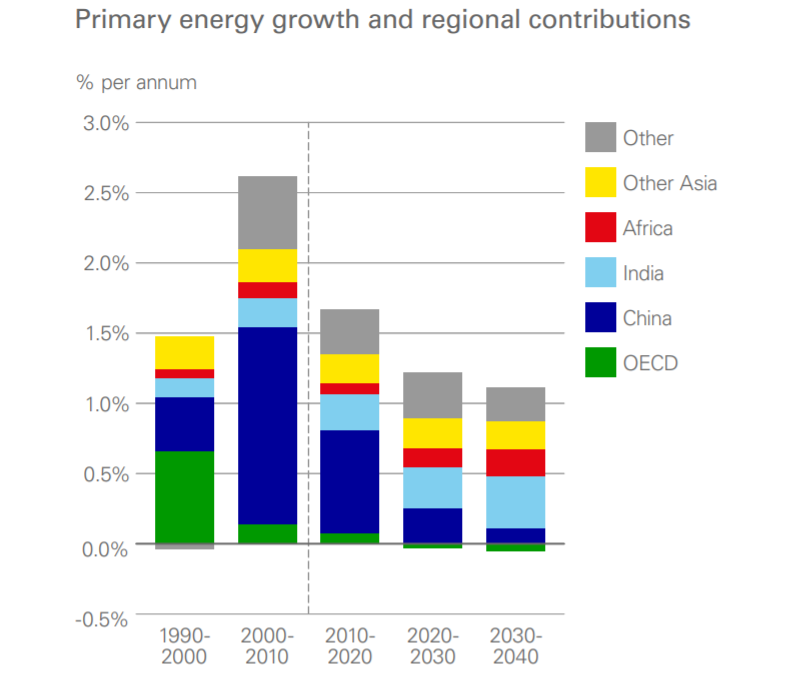

“People forget that when you look at forecasts for OECD countries, energy consumption going forward remains relatively static.

“In Asia, whether we like it or not, economic growth is massive. The region today already consists of more than 50% of primary energy demand and the rate of growth is significantly ahead of the rest of the world – something that will continue in the next 20 years.

“So unless we can solve the problem of the energy transition in Asia, my argument is we will not solve the energy transition problem at all.”

Energy trilemma highlights differences between West and East

The energy trilemma is a concept that’s been around for a long time in the industry, describing a triple challenge of ensuring access to affordable energy, maintaining energy security and achieving environmental sustainability.

But how that looks for people living in Europe is very different compared to those in Asia, where the priority is firmly on ensuring access rather than decarbonisation.

Of the top 30 countries in the World Energy Council’s Energy Trilemma Index, which ranks nations according to the balance they achieve across the three criteria, all are in Europe apart from New Zealand, Canada, the US, Uruguay and Australia.

China, meanwhile, is in 72nd place and India is 109th, although there are higher positions for Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore and Malaysia.

For an industry that straddles across all these regions – from both the OECD and non-OECD worlds – the “dilemmas and challenges are huge”, believes Dr Michal Meidan, director of the China energy programme at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

She says: “When you look at OECD countries, the basic issues of access are regarding access to Wi-Fi, Uber and Starbucks – not access to electricity.

“In South Asia, these countries rank lower on the index because even though they have access to energy, the trade-off is a high dependence on energy imports and the challenges of sustainability, which are growing day by day.

“The other thing to point out, of course, is Asia consists of 23 countries with very different economic profiles, resources, population sizes and stages of development – so we’re talking about a very diverse set of countries and challenges.”

Countries like China and Malaysia have enjoyed access to electricity for close to 100% of their populations for more than a decade, while significant progress has also been made by others.

Although many economies have been electrified, clean cooking remains out of reach for 1.7 billion people in the region, which the IEA says is home to 65% of the global population without access. For those with access, fossil fuels remain an important part of the mix.

“The main priority for many Asian governments is still electrification, access to electricity and growth in terms of standards of living and basic welfare,” adds Dr Meidan.

“As these countries have provided access to energy, this has taken a toll on energy security because they rely on imported energy, while the energy intensity is increasing too.

“The growth trajectory means there is more energy consumption and we can’t expect these countries will rely fully on renewables just yet, with coal still a part of their energy mix even though progress in access to renewables has been dramatic.”

Although stagnant in Europe, energy demand is expected to grow at about 4% in Asia.

But while the region is also responsible for the largest growth in energy consumption per capita at 3.3% in 2018, the 60.2 gigajoules (GJ) average remains way below the 182.6GJ average in the OECD, where there was 0.9% growth. Asia’s consumption is also below the global average of 76GJ.

Dr Meidan says: “For many Asian policymakers, the ambition is to get close to OECD levels, not for the sake of energy consumption but for what it represents.

“That’s access to mobility, driving, international transport and consumer goods – which are all petrochemical and natural gas-intensive, at least for now.”

This has translated into the energy mix, in which BP estimates coal accounts for 58% of China’s consumption – the figure is 47% in the wider Asia-Pacific and 24% globally – compared to 4% renewables.

It means the energy industry can see a market “that is hungry for fossil fuels”, while local authorities are more concerned with reducing air pollution in cities by scrubbing harmful pollutants and deploying “clean coal” rather than tackling the larger emissions problem.

“This brings us to the core of the dilemma in that you can reach something sustainable from a local air pollution perspective that allows you growth, access to energy and locally-supplied resources with coal,” says Dr Meidan.

“That’s not good for climate change and is very carbon-intensive, but when you look at it from an Asian perspective, it gets you to where you want to be.

“So sustainability is defined slightly differently when we look at it from the West and the East.”

What does the future direction for climate change look like in Asia?

China’s 1,000GW of coal power accounts for about 60% of its total installed generation capacity.

Research by the country’s electric utility operator State Grid Corp estimates it will need between 1,250GW and 1,400GW of coal-fired power over the long term to guarantee stable supplies.

The country has a pipeline of coal projects worth about 150GW but financing further schemes is becoming more difficult.

As of February 2020, 22 banks had ended direct financing to new thermal coal mine projects worldwide, while 28 banks had stopped funding new coal plants, according to the international campaign group BankTrack.

The group, which includes Credit Suisse, Standard Chartered, Lloyds Banking Group, Barclays, Santander, JP Morgan Chase, Société Générale and Deutsche Bank, may have another high-polluting sector in its sights next.

“Financial institutions are no longer willing to finance coal and very soon it’s going to be harder and harder to finance oil and gas-based projects,” says Dr Meidan. “Big oil and gas is going to be big tobacco very shortly.”

Again, the context is different in Asia.

So while securing investment for new fossil fuel projects from the West might prove nigh-on impossible in the near future, the Bank of China, China Construction Bank, Agricultural Bank of China and Beijing-based ICBC were responsible for about three-quarters of financing for coal-fired power plants across the top 10 backers for the sector in 2018 – to the tune of about $17bn, according to Dr Meidan’s figures.

At the risk of painting a picture that the East is fossil-fuel hungry and the West is clean, though, the Chinese energy expert points out the innovation coming out of Asia in renewables.

China has been the biggest investor in the world, spending $83.4bn in 2019 which, despite representing an 8% drop, was way ahead of any other country.

The US was second in the BloombergNEF table with $55.5bn after a 28% rise, followed by Japan ($16.5bn) and India ($9.3bn).

China’s total renewable capacity rose 9.5% in the first half of 2019, reaching 750GW according to the National Energy Administration as Beijing pushed for greater clean energy consumption.

By the end of the year, it was estimated the country could have had as much as 360GW in hydropower capacity, 210GW wind power, 200GW solar and 22GW biomass.

Dr Meidan adds: “We can’t just take it to mean that Asian developing countries are sitting back and saying ‘we have to develop and we’re not taking into account any of the energy transition’.

“They are making huge progress on renewables and on cleantech. But the growth of this need by far outpaces their ability to meet all new energy demand with renewable and clean energy.”

She is wary of the East versus West narrative this creates, citing how people have regularly asked her whether Asia actually wants to achieve zero coal in its energy mix.

“Well yes,” she adds. “But before that, it wants to get to 100% electrification rates and 100% access to cooking. So the zero coal target comes much further down the list of priorities.

“It leads to disgruntlement and outrage in the West, which thinks offsetting carbon emissions are only going to be made up by the East, so it doesn’t matter what happens there if the East continues to use carbon-intensive fuels.

“This isn’t a zero-sum game but we have to be open to the different forces and policy pressures that are at work.”

What is China’s position on climate change?

Despite roughly trebling since 2000, China’s emissions did flatten between 2014 and 2016 as the country’s ruling Communist Party set upon a climate policy that involved the renewables investment.

While they have increased again every year since then, Godfrey finds comfort in the intention from the highest level to tackle climate change.

Instead, the major challenge is getting the East and West to more effectively interact with each other in an era of trade wars, 5G network paranoia and IP disputes.

“To me, that’s the fundamental issue behind where the energy transition is going,” says Godfrey.

“It’s not about us and them – it’s about how the world sorts its problems out, but at the moment they find it difficult to talk to each other.

“Politics plays a big part and we need to address this head on. It’s not just an issue of energy – it’s deeper than regulatory change.

“It’s political culture that will need to fundamentally change if we’re going to manage the energy transition.”

So what do China and India have to say about the climate change problem?

Wang Qi, China’s minister counsellor for the UK and Ireland, tells an audience at IP Week his country recognises “green is good” and is now focusing on the “quality” of its energy stock.

“China is determined to make an important contribution to sustainable development and the global efforts against climate change,” he says.

“Scientific and technological innovation has played a leading role in China’s pursuit of green development and investment.

“It has been accelerating the transformation to upgrade forms of energy production and consumption.”

Addressing the accusation his country is “addicted” to coal, he claims it has built the world’s largest “clean coal” system, with its capacity of coal power generators that produce “ultra-low emissions” exceeding 800GW.

Reeling off more statistics, he says clean energy produced 24% of the energy consumed in 2019 and nuclear power generators either in operation or construction have a capacity of 58GW.

Meanwhile, China’s installed renewable energy capacity accounts for 30% of the world’s total and it has a 29% share of global green energy patents.

And when it comes to cutting carbon emissions, the country claims to be ahead of many other countries.

In 2018, it says the CO2 emissions per unit of GDP decreased by 45.8% compared to 2005, amounting to 5.26 billion tonnes of carbon.

Qi says China is committed to continuing this trajectory and happy to share lessons it has learned with the rest of the world.

“China is the undisputable leader in the energy transition around the world,” he adds.

“It remains unwavering in its resolve to address climate change, pursue sustainable and high-quality development, and deepen co-operation with other countries.

“China stands ready to work with friends from all walks of life. We want to provide a more transparent and non-discriminative environment.”

India also has a big role to play in Asia’s climate change approach

When Donald Trump pulled the US out of the Paris Agreement in June 2017, he lambasted the 6.5 million jobs and $3tn GDP that could be lost in his country by 2040 due to environmental regulations.

But he also jumped on the chance to take aim at both China and India – the world’s first and third biggest carbon emitters, sandwiched by the US itself.

In particular, he lashed out at how India would be allowed to double its coal production by 2020 while the US would be forced to get rid of its own fleet in a move that would cut coal mining jobs by 86% by 2040.

But in line with Dr Meidan’s argument, India’s position on the carbon podium – it produced 2.5 billion tonnes of CO2 in 2017, still less than half the US’ 5.1 billion tonnes despite its 1.3 billion population being roughly four-times that of America – results from the fact it has turbo-charged consumption of solid fuels like coal to drive economic reform.

Its GDP grew five-fold from 2000 to 2015, when it reached $2.2tn and its 2017 figure of $2.65tn placed India fifth in the world.

But access to energy is still a problem, with between 250 million and 300 million people estimated to be without an electricity supply into their homes.

Coal, which remains cheaper than imported oil and gas in the country, accounts for more than 70% of the power mix, but S&P Global Platts Analytics data shows its usage dropped for the first time in history in 2019 by 2% – following a 7% annual average growth over the previous five years.

The lower output can be explained mostly by the fact India’s electricity demand grew by 0.9%, which was a marked drop on the 6% annual growth between 2014 and 2018.

S&P’s head of global power planning Bruno Brunetti said in a recent blog that there is large resource potential in renewables, particularly solar, and strong policy support in India’s climate strategy.

But with 34GW of solar power and 37.6GW wind installed as of January 2020, he believes India has a long way to go to achieve its ambitious goals of 175GW renewable energy by 2022.

Such a target also seems conservative, given that some estimations suggest the country could need at least 400GW of non-fossil fuel capacity by 2030 to satisfy high economic growth projections while limiting emissions.

“Despite a bold policy agenda and competitive pricing, renewables development has also been hit by the broader structural issues facing the Indian power sector,” he said.

“Receivable delays have become a growing issue also for renewables developers, with high counterparty risks a concern for highly leveraged projects.

“Capacity successfully auctioned is only a fraction of the tenders, with cancellations or postponement becoming frequent last year.”

While China can aggressively roll out whatever it wishes when it comes to new power facilities, the Energy Institute’s Asia-Pacific lead Godfrey points out India has to overcome more political barriers.

“Unlike China, India is incredibly short in infrastructure,” he says. “China finds it very easy to put infrastructure wherever it wants because of the Communist Party, whereas India has a democracy and major regional politics.

“It also has a big remote population. However, India has done a remarkable role in providing energy to its people and is now moving ahead to developing a more mature energy infrastructure.”

Dr Leena Srivastava, deputy director-general for science in the Austria-based International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) research organisation, believes the situation in her country can be viewed from either a “glass half-full or half-empty” perspective.

But she points to India’s intended nationally-determined contributions – a set of ambitious targets – as evidence of the country’s dedication to ultimately tackling climate change.

They include reducing carbon intensity of GDP by a third by 2030 compared to 2005 levels, having already reduced this gauge 21% by 2014.

Renewables made up 35% of India’s installed capacity and 17% of electricity generation in 2019, but the goal is to increase the latter figure to 40% by 2030.

“The biggest challenge as a country is to be nimble and adapt to the different challenges that come along,” says Dr Srivastava.

The West can help Asia in beating climate change

She admits the developing world – India and China in particular – must bear its responsibility for a hefty amount of emissions that need to be cut in the foreseeable future.

But Dr Srivastava also wants developed nations, namely the US, to bear the burden.

“Where we are now is not for a lack of effort as there’s a lot of ambition going into cleaning the energy system,” she adds.

“We expect India’s energy demand will continue to grow and we still have a very large poor population.

“But there’s a lot of support needed from the international arena because we seem to have lost the idea of shared responsibility.

“Expecting everyone will get to net zero at the same time will just lead to disappointment. It’s an interlinked world – we’re all in this together and we need to look at how we can all carry the cost.”

The story of climate change is often told on an East versus West battleground but as many voices in the industry increasingly stress, developing nations in Asia and beyond need the help of the wealthier countries with which they share a planet.