Metal companies must scale-up quickly if enough lithium-ion batteries are to be made – and help automakers realise their “pipe dream” of a full transition to electric vehicles, say analysts.

While car brands like Volkswagen could aim to release the first ever “carbon-neutral car” at some point this decade, experts of the commodities world believe they must first get to grips with a supply chain that’s been largely alien to them until now.

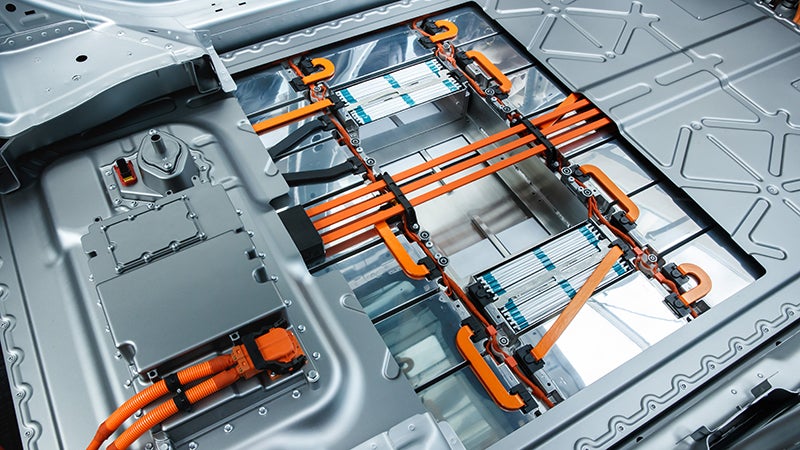

And the major task for manufacturers will be solving the capacity issues in providing enough materials like lithium and cobalt to build the batteries.

Simon Moores, managing director of price reporting agency Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, told the energy industry conference IP Week in London last week: “Scale is by far the number one challenge.

“These raw material industries don’t have big thinking – they think in 1,000-tonne denominations, not 100,000 denominations – and short-term because no one wants to take the risk.”

Securing supplies, ensuring the quality of commodities and understanding speciality chemicals are other challenges but he believes automakers are now beginning to drive the supply chain with the aim of achieving price parity for EVs with petrol and diesel cars in the near future.

“They want to control the whole supply chain and drive down the cost on everything every year, no matter what,” Moores added.

“It’s an interesting culture clash, with automakers trying to negotiate the cobalt price when it’s run out – they’re not used to hearing that.

“But this circle is virtuous. Building gigafactories is giving confidence to automakers to build more EVs, this is giving confidence to the upstream raw materials guys to expand until about 2024 to 2025 – but what happens after that?

“The industry knows EVs are being built but the challenge is scaling up and removing bottlenecks – because if you don’t have the raw materials, the whole thing gets slowed down and that’s the big problem at present.”

Rise of electric vehicles and lithium-ion battery megafactories

A convergence of China’s growing fascination with electric vehicles, VW’s Dieselgate in September 2015 and the release of the first Tesla Model 3 six months later helped to spark a “true interest” in EVs globally, believes Moores.

This has also stimulated the rise of battery megafactories, with the absence of enough high-quality energy storage encouraging Tesla to bypass the middleman and open its first gigafactory alongside Panasonic in 2016, with two others since built and another in the pipeline.

Foxconn Technology Group, the Chinese manufacturing giant that has made products including the iPhone and PlayStation 4, and South Korea’s LG Chem have also been drawn into making plans for plants.

The market size for lithium-ion battery cells has grown from 55 gigawatt-hours (GWh) in 2015 to 225GWh in 2020, according to Benchmark.

While there were three lithium-ion battery plants in 2015, there are now 121 either built or in the pipeline.

By 2029, the planned total capacity is 2,224GWh – roughly 10-times the current size and enough to power 38 million fully-electric vehicles – with new developments largely led by China, along with a supporting cast of Europe, the US and South Korea.

Moores said: “The question we get a lot around the world is ‘when is the electric vehicle thing happening? When is this party going to start?’

“Well it already has – it’s grown four-times in the past five years since we started in January 2015, but the challenge now is getting it to scale 10-times in the next 10 years.

“The industry needs outside companies coming to do that – it can’t do that itself because it doesn’t have the thinking or money – and that’s the opportunity for others.”

More materials needed to scale-up production of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles

To feed a 30GWh battery megafactory, 33,000 tonnes of graphite, 25,000 tonnes of lithium, 19,000 tonnes of nickel and 6,000 tonnes of cobalt will be required, claims Benchmark.

And these raw materials don’t come cheap, with the analyst estimating 79% of the cost to manufacture a Tesla Model 3 battery – which makes up 27% of the total vehicle cost – comes from the minerals, metals and chemicals that create the 4,416 lithium-ion cells used in the battery.

But there have been problems with matching surging demand with supply, given that these materials are produced at relatively low amounts and batteries are often only a small part of the industries.

For example, the price of lithium rose four-fold between February 2015 and November 2017, before settling by January 2020 at a level still relatively high historically.

Moores said: “Historically, lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide sat at between $5,000 and $7,000 per tonne, but then they went up to $20,000 to $25,000 per tonne because of what was happening in China with the introduction of electric buses.

“Battery demand increased four-times and it drove that price very high because the producers couldn’t react, as it’s only a 300,000-tonne industry per year.

“They’re slow to react, inflexible, and maybe didn’t want to over-invest without knowing whether this is real.

“We believe lithium is going to be short this year and this price spike will happen again both this year and next.

“There hasn’t been enough investment and this, in a nutshell, is the problem with these raw material industries.”

He added that if all the planned megafactories come online at full utilisation, they will require 1.9 million tonnes of lithium, but only 390,000 tonnes is currently produced – with a similar story for nickel, cobalt and graphite.

“There will be an increase of between five and 10-times within an eight to 10-year period.

“These mining guys have never seen growth like this in any commodity throughout their entire career, so you can see why it’s difficult.

“People love the opportunity but they’re scared to invest, and there’s a conundrum in the industry at present on who takes the risk.”

Despite the material cost fluctuations, Moores said the price of a lithium-ion battery has decreased from an average of about $400 per kilowatt-hour in 2015 to $120 in 2020 due to the increased megafactory capacity.

“So they’re getting cheaper, more abundant and much better – on an energy density basis, they’re about 10% better than five years ago,” he added.

“The car, energy, minerals and chemicals industries are all merging and converging on lithium-ion batteries.”

Lithium-ion battery supply chain issues facing electric vehicle manufacturers

Benchmark’s head of forecasting Andrew Leyland claimed every electric vehicle made has been sold, suggesting that the market is only being constrained by supply rather than demand.

“An electric vehicle is a substitute product,” he said. “The industry wants to sell it at a price point defined by the internal combustion engine because otherwise people won’t buy one.

“The issue they have is that all the contract structures in the supply chain are on a cost pass-through basis, so they have to internalise this price risk as they can’t pass it on.

“That works fine when 1% to 2% of your vehicles are EVs because they can be loss leaders – but when you’re planning for 50% of your production in the future of your company, you really need to take an interest in your supply chain and there are signs they are starting to do that.”

He claimed OEMs have “got themselves into problems” by making big announcements related to increasing EV production because the supply chains don’t currently enable them to scale-up as quickly as they’ve promised.

“They can see the issues the industry has between 2025 and 2030 if they want to increase their EV output by four, five or 15-times, and therefore the raw material consumption,” Leyland added.

“We’ve not yet seen an announcement about a big investment in the supply chain and raw materials but that’s coming.”

Electric vehicles will bring greater supply chain scrutiny

For the suppliers, they will also be forced to confront issues they haven’t dealt with until now.

Given the environmental discourse surrounding EVs and the wider transport industry as it aims to decarbonise, all parties involved should prepare for questions about the carbon emissions of producing supposed zero-emission cars.

Leyland said: “Everyone needs to know the carbon and ethical footprints, and it’s a huge issue. You ask OEMs about the footprint of their current supply chains and they haven’t got a clue.

“But these days, when it comes to things like cobalt and the Democratic Republic of Congo – where 70% of the world’s cobalt comes from – it’s a huge issue for them to think about.”

Nina Skorupska, chief executive of the Association for Renewable Energy and Clean Technologies (REA), added: “Scrutiny is absolutely through the floor for any new technology that’s going to be mass-adopted.

“Woe betide an OEM that goes forward and doesn’t pay attention to environmental and ethical issues because people will vote with their feet, and will abandon that brand.

“So many things have changed in the past five years in terms of people’s awareness of things that are important.”