In March 2020, Opec and its allies failed to agree measures over how to co-ordinate a response to the spread of Covid-19. The result was an oil market crash and a price war between two of the world’s most powerful producer nations. Here we profile the controversial organisation and trace the story of how it became entangled in one of the most significant market upsets of recent times.

Fluctuating oil market conditions can have big consequences for the stability of global financial systems — and, in particular, on developing economies heavily dependent on oil revenue.

The 2020 oil price crash, driven in large part by the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, is the latest example of how volatility in commodity trading can have a wider financial impact on the global economy.

That is why sixty years ago, an intergovernmental association was formed known as the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, or Opec for short.

Its website states the following ambition: “Opec’s objective is to co-ordinate and unify petroleum policies among member countries, in order to secure fair and stable prices for petroleum producers, an efficient, economic and regular supply of petroleum to consuming nations, and a fair return on capital to those investing in the industry”.

In the years since its formation, the organisation has steadily grown its membership – currently comprising 12 major oil-producing nations, although this is a regularly-changing number.

Today, Opec is nominally led by Saudi Arabia, a country that holds almost a fifth of proven global petroleum reserves, and is the world’s biggest crude exporter.

The group has been criticised in some quarters for operating like a cartel — co-ordinating among its ranks to control the global supply of oil to maintain high prices — although its members dismiss that label as untrue.

Here we take a closer look at Opec, its history, membership and global influence.

What is the history of Opec?

Opec was founded in Baghdad in September 1960, by five original members — Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela — for the stated purpose of ensuring the “inalienable right of all countries to exercise permanent sovereignty over their natural resources in the interest of their national development”.

The idea, Opec says, was to wrest control of oil markets from the “Seven Sisters” – a group of multinational oil corporations which dominated the industry at the time, and now through a series of mergers and acquisitions exist as some of the world’s largest oil majors including ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP and Royal Dutch Shell.

Originally headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, the organisation later moved its base of operations to Vienna, Austria, where meetings are now held every year for producers to discuss matters of business and make policy decisions.

The group is administered by the executive leadership, headed by the Opec secretary-general — a position currently held by Nigerian politician Sanusi Barkindo.

Who are the members of Opec?

Membership of the organisation has evolved over the years, with countries regularly joining and leaving, and in some cases re-joining again.

Ecuador was the latest nation to end its affiliation with Opec, confirming its decision in late 2019 and effective as of January 2020.

That leaves the group with 13 members at present: Algeria, Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates and Venezuela.

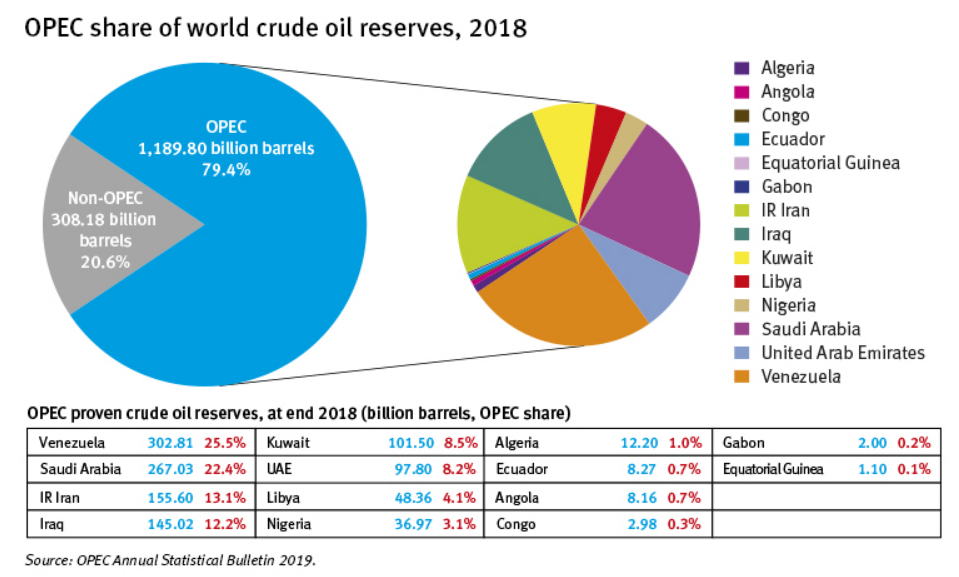

Together they account for more than 75% of known crude oil reserves — just under 1.2 trillion barrels — giving the Opec collective huge power to exert influence over international oil markets.

The challenge of US shale

While Opec has been able to dominate crude oil supplies since its inception, the US shale revolution in the mid-2010s, facilitated by advances in fracking technology, brought a new dynamic to world oil markets.

Global inventories were suddenly saturated with cheap US shale oil, putting pressure on crude prices and taking market share from Opec producer countries.

In response, the organisation formed an alliance in 2016 with 10 non-Opec countries led by Russia, agreeing to make co-ordinated production cuts in an attempt to stabilise the market and uphold the price of crude.

Libya and Nigeria were afforded exemptions from the original deal due to domestic conflict issues.

What is the Opec+ alliance?

Joining Russia in the informal co-operation arrangement with Opec are Mexico, Kazakhstan, Oman, Azerbaijan, Malaysia, Bahrain, South Sudan, Brunei and Sudan.

Since 2016, this so-called Opec+ alliance has sought to maintain crude oil prices through a series of agreements to regulate production and avoid oversupplying the market.

That was until March 2020, when Russia defied Opec’s proposal to introduce fresh cutback measures designed to respond to weakening oil demand brought on by the spread of Covid-19 — with flight cancellations, quarantine measures and low industrial activity combining to dramatically reduce fuel consumption around the world.

Opec had suggested extending existing production cuts of 2.1 million barrels per day (bpd) among the Opec+ alliance, as well as a deepening of the measures by a further 1.5 million bpd, until the end of 2020.

Russia’s refusal to accept the new terms has cast the future of the informal relationship it, and other the non-Opec producers, had been cultivating with the organisation into doubt.

Oil prices plummeted on the news that measures to stabilise the market had fallen through, and the situation was exacerbated further still when Saudi Arabia announced it would begin to ramp up production and offer discounted crude – effectively launching a price war with Russia and US shale producers.

Some analysts suggest the depth of the oil price crash will bring Saudi Arabia and Russia back to the negotiating table, but for now the future of Opec+ remains very much an unknown.

Meanwhile, Opec’s position as a supposedly stabilising influence on global oil markets will be called into question if it proceeds to open the floodgates at a time when global financial systems are already struggling under the weight of the coronavirus pandemic.