The latest climate pledges made by governments at the US summit have drawn the world closer to achieving the goals set out in the Paris Agreement.

Under the international climate pact, which was signed by 197 nations in 2015, participants aim to cap the rise in global temperatures at “well below” 2C above pre-industrial levels by 2100, with 1.5C being the ideal scenario.

Those targets had looked out of reach during former president Donald Trump’s time in the Oval Office, after he removed the US, the third-highest emitter, from the Paris Agreement and championed a free-market policy in which all fuels and technologies had an opportunity to contribute to the national goal of energy dominance.

But, after President Joe Biden reinstated the nation into the accord and earmarked $1.7tn worth of investment over the next 10 years for a “clean energy revolution”, reaching the goals are not a lost cause just yet.

The global efforts also received a welcome boost at Biden’s climate summit at the end of April, where his administration set a target to cut 50-52% of US carbon emissions by 2030 compared to 2005 levels.

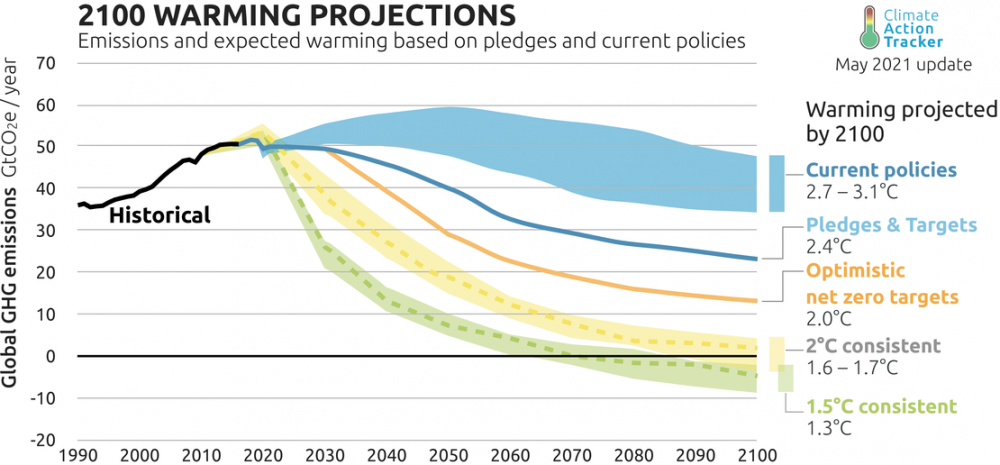

Various other major economies also took the conference as an opportunity to enhance their climate ambitions and, according to analysis by the Climate Action Tracker (CAT), those upgraded Paris targets have brought down projected end of century warming by 0.2C to 2.4C.

“It is clear the Paris Agreement is driving change, spurring governments into adopting stronger targets, but there is still some way to go, especially given that most governments don’t yet have policies in place to meet their pledges,” said Bill Hare, CEO of Climate Analytics, one of CAT’s partner organisations.

Latest US Summit climate pledges could limit global warming to 2C by 2100

Under the Paris Agreement, parties are encouraged to formulate and communicate their “long-term low greenhouse gas emissions development strategies” and have been invited to communicate those proposals to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) before COP26 in Glasgow, UK, in November 2021.

Assuming full implementation of the net-zero emissions targets by the US, China and other countries that have announced or are considering such ambitions, but have not yet submitted them to the UNFCCC, CAT believes global warming by 2100 could be as low as 2C.

Currently, 131 countries, covering 73% of global emissions, have either adopted or are considering net-zero targets.

But CAT notes it is the updated 2030 nationally determined contributions (NDC), where each country defines their own climate targets and contributions to help reach the universal ambitions, that contribute the most to the drop in projected warming, highlighting the “importance of stronger near-term targets”.

The biggest contributors to the drop in projected warming are the US, the 27 EU members, China and Japan – but China and Japan are yet to formally submit a new 2030 target to the UN.

Canada announced a new target, South Africa has an increased target under public consultation, Argentina has announced a further strengthening of the target it submitted last December, and the UK has announced a stronger 2035 target.

While the leaders of India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Turkey all spoke at the US summit, none of those nations announced stronger NDCs. But South Korea, New Zealand, Bhutan and Bangladesh all committed to submitting stronger targets this year.

Brazil brought forward its climate neutrality goal by 10 years to 2050, but has changed its 2030 baseline, making its short-term target weaker.

It isn’t the first time the South American nation has been in the spotlight for its climate commitments, after it has been accused of holding up the progress of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement – a key mechanism that would allow countries to co-operate by trading their emissions allowances.

Brazil argues that its forests should be counted as carbon sinks towards its national emissions targets, which would mean it can relax efforts to cut emissions in other areas.

While Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison said he wants his country, which is the highest per capita carbon emitter amongst the world’s richest nations, to achieve net-zero emissions “as quickly as possible and preferably by 2050”, he didn’t upgrade its 2030 target – a goal the government claims it is already “on track” to beat.

Paris Agreement pledges for 2030 brought down gap to 1.5C scenario by 11-14%

More than 40% of the countries that have ratified the Paris Agreement, representing about half global emissions and about a third of the global population, have submitted updated NDCs.

The CAT’s final calculations on the 2030 emissions gap between Paris pledges and a 1.5C pathway show it’s been narrowed by 11-14%.

“The wave towards net-zero greenhouse gas emissions is unstoppable,” said Niklas Höhne of NewClimate Institute, one of CAT’s partners.

“The long-term intentions are good. But only if all governments flip into emergency mode and propose and implement more short-term action, global emissions can still be halved in the next 10 years as required by the Paris Agreement.”

The CAT’s analysis sets out the key measures that governments need to take to get emissions onto a 1.5C pathway.

While the renewable electricity and electric vehicle sectors are showing plenty of promise, and the technology is there, it said the development of new technologies for the industry and buildings sectors is “too slow”.

It also pointed out that contrary to the Paris Agreement is the persisting plans of some governments to build new infrastructure such as new coal-fired power plants, increasing uptake of natural gas as a source of electricity and a trend towards larger, less efficient personal vehicles in some countries.