Both environmentally and economically, energy loss for some of the world’s biggest suppliers is a huge issue.

According to the International Energy Agency, the improvement rate for energy efficiency had slowed for the third consecutive year in 2018, with intensity falling by 1.3%.

The intergovernmental organisation also claims, in the same year, this issue was the biggest source of carbon dioxide emissions in the energy sector.

In an effort to tackle the problem, some companies are turning to technology to reduce the amount of loss emitted from any one facility.

One such firm is Norwegian energy company Lundin, which is using data to manage and mitigate the issues of energy loss by assessing the quality of its equipment and the way it’s deployed.

How Lundin began to implement technology in order to combat energy loss

The system has been implemented on Ludin’s Evard Grieg platform, which is situated in the North Sea.

Based around 200 kilometres away from Norway and on the border of the UK, the facility is a producer of both oil, which it sends to the former, and gas, going to the latter.

The platform currently exports around 23,000 cubic metres of oil from this platform a day.

As an emitter of CO2, the Norwegian Environment Agency has provided the firm with an emissions permit, which it has to follow specifically in regards to the maximum amount of CO2 and chemicals that can be released by the site.

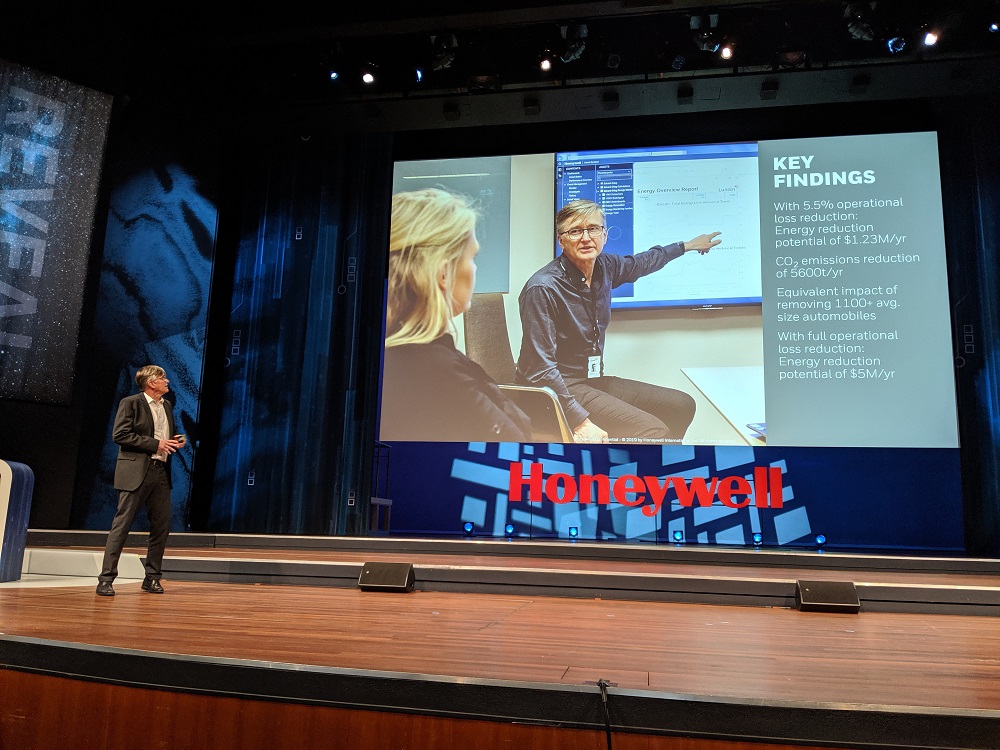

Speaking at technology company Honeywell’s User Group conference on 25 September, one of the firm’s principle engineers Stig Pettersen said: “We saw that we need a system or a tool for performing energy management.

“The important thing that we need is some digital tools for quality and better results from this.

“We worked together with Honeywell and implemented some digital tools as a basis for doing that.”

Pettersen explained the use of the data is designed to better understand how much energy the site produces, and implement activities in order to mitigate any energy lost.

He said: “The older and older and older the platform will be, the more and more and more energy we will use.

“So our goal is to, yes we will still use more energy when the field is empty or emptying, but we want to use less energy.

“Then we have the energy loss calculation and optimisation, we are looking at this loss compared the facility working at optimal operation.

“This means, if for some reason any piece of equipment is doing worse than that, this is something we can see online immediately and deal with.”

How Ludin is effectively using the data it’s gathering from its Evard Grieg platform

In order to most effectively understand and deal with any issues arisen on site, the team at Lundin split the data into two types of energy loss, assessing either whether inefficiency is caused by the way something is designed or by the way it’s operated.

Using the data gathered over the course of a two-month period between 1 July and 31 August 2019, it found it was losing close to 50% of its potential energy production capacity due to either the way equipment was designed or operated.

This amounted to the site inadvertently releasing the equivalent of 8,648 tonnes of CO2, with an estimated revenue lost of more than 16m Norwegian krone ($1.7m).

Lundin believes design energy loss is due to how efficiently something has been built to operate its particular function, and can only be reduced by either replacing or modifying the equipment in question.

Operational loss is commonly caused when a piece of machinery is either faulty or is not being used to its full capacity and can be adjusted by either repairing or changing the way it’s operated.

Pettersen said: “We are putting in key performance indicator (KPI) limits into our system in order to track losses looking at where we should be, and if we are below it we have a red light.”

Using the findings it was able to gather from the data, Lundin believes it could potentially save $5m of energy a year.

It also estimates this energy saving would reduce the amount of CO2 the facility emits by 5,600 tonnes a year, an equivalent impact to taking more than 1,100 average sized automobiles off the roads in the US.